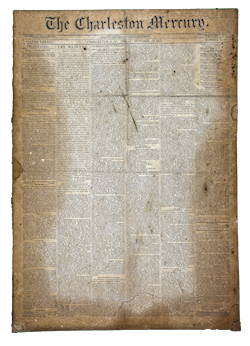

March 26, 1861; The Charleston Mercury

We stated yesterday that it was unmistakeably the idea entertained by the body which formed the Confederate States Constitution, to admit hereafter into the new Government the States of the Northwest, Pennsylvania, New York, &c., the power being given to futures Congresses of doing so by a two thirds vote. We urged the importance of at once educating the public mind throughout the South upon the impolicy and danger of reorganizing on any terms, the political connection with the North just severed. The dissolution of the Union was both rightful and expedient. It was a step essential to our peace, or equality, our prosperity and our development. Were the causes, which have brought us into peril and rendered a separation necessary, temporary and evanescent, it would be well to look to a readjustment of our intimate relations with those who have nearly threatened us with degradation and ultimate ruin. But the sources of our troubles are not of today, nor are they shifting and transitory in their nature. They are the growth and product of many years systematic persistent cultivation. They are as deep rooted and stable as the hard characteristics of the stubborn Yankee race. The Union has been dissolved in consequence of the steady, long, increasing and now predominating hostility evinced by the whole North towards the South. For years the Southern peoples have, with unexampled patience, endured the unceasing assaults of Northern interests, Northern ambition and Northern fanaticism, placed in direct antagonism to their just rights and vital institutions. As a matter of self preservation and self respect they have at last placed themselves beyond the reach of this incessant and harassing warfare waged upon them under the privileges of a common government, and to promote their designs. We now have a government of our own to meet their government. Before it will be desirable, wise or possible to take such enemies again into the fellowship of a common government, the plainest common sense dictates that a vast change must come over their feelings, their political opinions, and their policy. How probable such a change is and how soon it is likely to occur to an extent to justify their admission, depends upon the facts of their past history and present condition in these respects.

We know that the views of the universal Northern people, in regard to the nature and powers of a general government, are radically wrong. Their only idea is a consolidate government over one aggregate people–a nation, with a national government–the States mere territorial divisions, for the sake of convenience of reference and certain local matters of small importance. Can such a pernicious view be eradicated in a day, or a year, or a dozen years, with people who have been brought up in error so dangerous and radically unsound?

We know that the grand cardinal principle of their republicanism is the bald, unchecked sway of numbers. “The majority must govern,” the minority must yield–absolutely acquiesce. From being only an instrument of securing justice to the citizen – with checks and balances for the protection of the weak and few – government thus degenerates into a capricious and oppressive tyranny, as rapacious as it is responsible. Can those who entertain such low views of free government; with whom liberty is license–democracy, mobocracy; whose idea of the object of government is profit; whose statesmen are demagogues; the whole tendency of whose politics is to level downwards into one pestilent mass of popular corruption and demoralization; who scout at conservatism, and revel in all the vices and follies of agrarianism and higher law ethics–can such peoples be safe or valuable confederates for the Southern States? Is there any reason to believe that these dangerous and anarchical doctrines will be speedily or not very remotely abandoned?