Camping, Travel, and More...

This article, by Andrew R. Boone, appeared in the April 1936 issue of Popular Science Monthly.

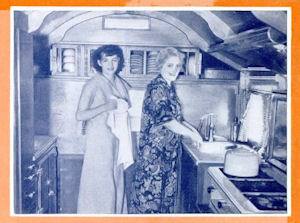

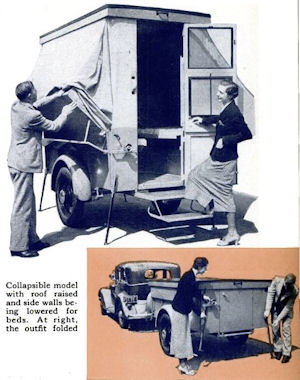

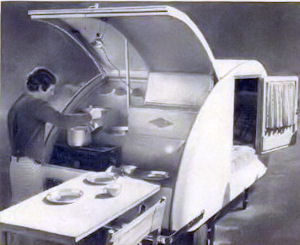

Dish washing is a simple task in this traveling kitchen. Below, a trailer of streamline design.

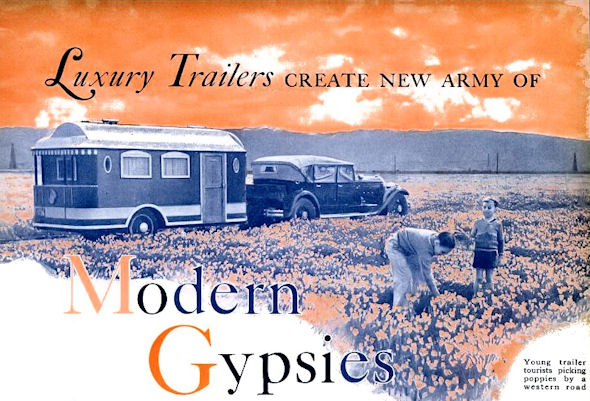

America Takes to the Open Road for Business or Pleasure in Amazing New Homes on Wheels

By Andrew R. Boone

America's homes are rolling.

Fully 1,000,000 people this year will step into 250,000 comfortable, house-type trailers and speed away to distant scenes—the majority for pleasure; some for business.

Seven years ago, trailers in which you could live as you traveled were virtually unknown. For four years, the public looked on them with skepticism.

Then trailers caught on. Three years ago, they swept the East in a single season. Quickly the trailer boom rolled across the continent. Today, in every section you'll see these single-room houses—complete homes, from dining room to kitchen—zipping along the highways, performing all sorts of services, from carrying the family on vacation into the mountains, to supplying display rooms for salesmen.

The very strangeness of the jobs they perform proves their utility, comfort, and economy. Preachers preach from them; actors use them as dressing rooms; workmen club together and use trailers as economical and easily portable homes; families use them as spare bedrooms, sleeping as many as six in a single unit.

Traveling homes and workshops—at a cost of no more than a fourth of a cent a mile!

Recently, I sought out for the readers of POPULAR SCIENCE MONTHLY some

of these trailer tourists, hoping to find out where they were going—and

why.

"How much does trailer travel cost?," I asked. "What do you get for your

money? Is traveling by trailer really pleasant and comfortable? For what

purposes can people use trailers?"

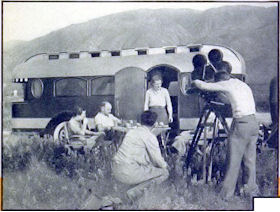

This roomy vehicle carries motion-picture personnel and equipment for making short colored features

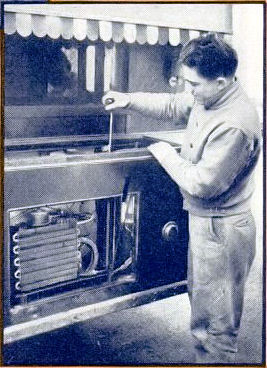

A tourist pumping up the air-pressure tank that supplies water to the sink. The coils serve the refrigerator unit.

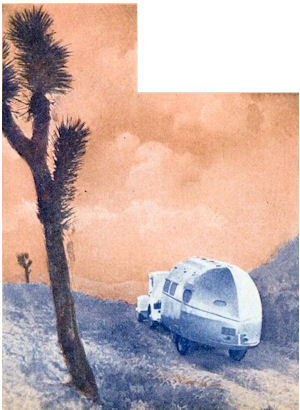

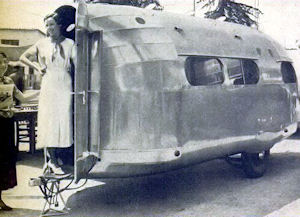

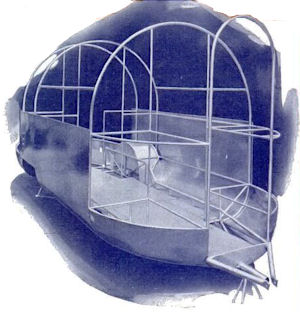

Above, an airplane-type trailer planned by W.H. Bowleus. As shown

below, it is caonstructed like a cabine plane.

The answers I got are interesting. Trailers have become far more than makeshift trucks in which to carry a fly rod, gun, and camp equipment. With them, you need no tent. Trailers, even the house kind, will travel virtually anywhere you can go. They're more, even, than just a means to a vacation. Suppose we take the last question first. Who's doing what with trailers?

Jack Bartlett, Tucson, Ariz., showman, recently purchased a trailer for $395, loaded into it a trained donkey weighing 800 pounds and a trunk containing fifty horned toads. With these as his performers, Bartlett tours the southwestern United States staging toad races and exhibitions of animal intelligence in hotel lobbies and schools.

Francis Olmstead, a writer for motion pictures, lives in his trailer, stopping on the desert or in the mountains, when the spirit moves him, to pound out his scripts far from Hollywood. A signal-maintenance crew on a railway between Los Angeles and Salt Lake City, travel in a trailer, pulling off the highway periodically to examine and repair ailing units. Not long ago, the president of a hotel company arrived at a hotel-men's convention—in a trailer. In Ypsilanti, Mich., a commercial photographer maintains a fleet of three mobile photographic trailer studios, complete with artificial lights and ventilation equipment.

An eastern man and his wife have set up a miniature toy factory and travel along the Atlantic seaboard selling their products to small-town merchants. Several artists use their trailers as studios.

Think of some odd use for a trailer, and likely some one, somewhere in the United States, already has been struck by the same idea. An itinerant minister, traveling through sparsely settled sections of the West, has converted a house-type trailer into a portable church. He seats a dozen people, preaching from a small chapel and pulpit at one end. A woman evangelist, Mrs. Julia A. Locke, tours the country in her trailer, preaching from a platform while music is provided by a bungalow-type piano carried within.

Many trailers are traveling restaurants. M. L. Skinner of Rochester, N.

Y., operates a hot-dog stand from one end of his, and lives in the

other. Living quarters and restaurant are separated by swinging doors.

He earns a good livelihood as he travels carnival circuits, selling to

carnival people and public alike.

One salesman, minus both legs, overcame his handicap by moving from town

to town and selling time switches, using the coach to display his wares.

His assistant, who likewise serves as chauffeur, drives the trailer to

the front of a prospect's office and invites him to see the display. The

request is so unusual that few decline. A pleasant chat usually results

in a sale. Again, half the rolling house is equipped as a bedroom and

kitchen.

More than one family has abandoned the city to combine business with pleasure in a trailer. Accompanied by his wife, Roy L. Haslett, demonstrator of fishing tackle, drives 20,000 miles yearly, home and business headquarters never more than ten feet distant from the steering wheel. H. K. Lewis and members of his family tour the United States every year giving professional theatrical performances. They park the trailer near the theater, don costumes and grease paint, and walk through the stage door ready for a performance. George Bucey, who sells women's clothing, carries 1,800 dresses on racks in his rolling salesroom, and displays them to prospective purchasers at the curb. At night, he curtains off the samples and enjoys the comfort of his rolling home.

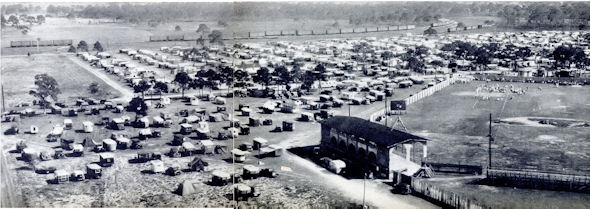

A city of trailers - a tourist park at Sarasota, Fla., with nearly 1,000 units assembled for the convention of a trailer organization. Many camps now provide facilities for this type of travel.

Four workmen engaged in constructing gas lines in the Middle West save rent as they move from job to job by "batching" in their trailer. Instead of paying rent of sixty dollars or more a month, they live in their trailer for less than five dollars. Elsewhere, families beat the high cost of living as they follow seasonal occupations in the beet fields of Colorado, the Texas cotton plantations, berry farms of Kentucky, and California's fruit groves, by living in trailers.

Some astounding mileages have been rolled up during the short time trailers have been in vogue. Virgil Dickie, of Detroit, has covered the amazing distance of 200,000 miles in five years, at a trailer cost of slightly more than one fourth of a cent a mile. I heard of a dozen other veterans, each of whom has gone far enough to girdle the globe four times.

You can cook, eat, and sleep in comfort while skimming along at sixty miles an hour in a lightweight, well-balanced trailer, or while stopped in the sun on a burning desert or in heavy snow. Weather means nothing to these rolling homes. It has become a common occurrence for meals to be prepared on the fly, to be eaten when the built-in telephone announces "dinner" to the driver. He pulls up alongside the road, walks twenty feet to the trailer door and partakes of a meal, the equal of any prepared at home.

In a trailer, your family can ride virtually twenty-four hours a day without undue fatigue. One man solved the problem of driving a long distance in a short time by taking the wheel during daylight hours while wife and children slept. She called him back for dinner, which she cooked as they rode, after which she drove while he washed the dishes and tucked the children into their beds. After a refreshing nap, he again took the wheel.

A "home on wheels" on a Nevada road in winter. Built-in heating and air-conditioning provide comfort under all climatic conditions.

W. H. Kellogg, associate professor of psychology at Indiana University,

recently made an 8,000-mile trip into western parks. Once, desiring to

get through some uninteresting country in a hurry, he drove all night,

while Mrs. Kellogg and the two children slept. Again, he stopped to buy

apples from a farmer; Mrs. Kellogg busied herself with the collapsible

oven and 100 miles farther on sounded the buzzer to announce the pie was

finished. For ten weeks, the Kelloggs never had a meal away from their

trailer.

"It was by far the most enjoyable vacation we ever had," he said, "as

well as one of the cheapest. We had no rent or hotel bills to pay and

the food expense was the same as if we had been at home. Our only extra

expense was for gas and oil."

In a modern rolling home. At the left, the "housewife" is cooking over a gasoline stove. A ventilator removes fumes. Meals are served on a folding wall table, and Pullman-type beds provide comfort. Note the built-in, bedside table.

In another three or four years, trailer manufacturers predict, fully 1,000,000 rolling houses will be following lanes and highways, carrying owners from colder to highways, and across mountains.

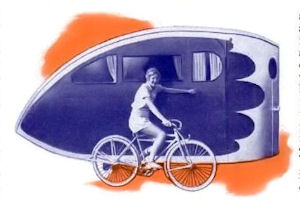

A "teardrop" trailer designed to accomodate two persons. Below, one of the smaller units that have cooking facilities at rear.

The reason for this prodigious increase is partly-economic. “With the rising cost of real-estate taxes, it is only natural that people are seeking new means of cutting down their living expenses,” one man who has built several hundred trailers told me. “The man living on a small pension, for instance, can live in a property-tax-free rolling home, moving whenever and wherever he chooses, on an income of fifty dollars to $100 a month. He may reside in a southern state during the winter at no greater cost than his coal bill in the North.

“Another large group who eventually will come to trailers are the owners of summer cottages, who will find in the trailer a cottage which can be transported to more desirable locations. Others who will come to occupy these portable homes are those suffering from heart ailments and other diseases which can be helped by climate and altitude. People who have some spare time during part of the year are turning by thousands to trailers—show people, teachers, and athletes, for instance.”

The typical trailer of today is a one-room affair, with the kitchen usually a part of the combination living-dining room. As the vehicles become more popular, they are rapidly changing form. People who start this season with an inexpensive unit, next year will be adding electric refrigeration, shower baths, and hot water. Next, they will divide their single room into two or three. Then will be achieved the real homes on wheels.

Trailers probably will never exceed twenty-five feet in length, no matter into how many rooms they may be divided, for taxes in many states skyrocket when that length is exceeded. From my conversations with a score of manufacturers, I think the trailers of next year and the year after will rival airliners in the comforts and conveniences crowded within a small space. Too, you will be able to store a small trailer with your car in a single garage, while a double garage would be required for the larger, more luxurious type.

Here are some of the things you'll get as trailers advance:

Even the small, less costly units will have full air conditioning for comfort in both summer and winter. The majority will be streamline and weigh less than the present average of about 1,300 pounds. Most of them will come equipped with radios. while light-metal-alloy body construction is gaining in favor. All will have easily cleaned upholstery and beds as comfortable as you'll find in good hotels. More expensive trailers will be equipped with brakes operated from the driver's seat, and the majority will be soundproofed.

Meantime, how much do you have to pay for a trailer, and what will you get for your money? The range is wide, from $100 for the simplest kind of camping-type trailer to $14,000 for a de luxe house trailer with beds for six people. In the former, you get little more than a two-wheeled truck for carrying your bed and other supplies, while the latter boasts electric refrigeration, air-conditioning equipment, insulation against heat and cold, telephone system between trailer and car, ice water—all the comforts of home.

For $395 you can purchase a comfortable house trailer, finished to match your car, with a bed for two, plus a dresser, sink, and water piped to the sink. With good care, such a unit will give satisfactory service a decade or longer.

If you wish to add $100 to the purchase price, you'll get a similar unit, with sleeping accommodations for four—one double bed and two singles for the children.

Step up the price to about $795, and you'll find yourself contemplating a fine mahogany interior finish; taking food from an ice box; sleeping in a Pullman-type bed; cooking meals over a three-burner gasoline stove whose fumes escape through a ventilator in the roof ; drinking water piped from storage tanks to a hand pump at the sink, which is hidden under a cutting board; and using a separate dressing room and compact closets to keep your clothing clean and neatly pressed.

While that unit carries no brakes, if you wish to climb into the $1,500 class, vacuum brakes will be added, plus electric refrigeration, a portable electric-light plant, gasoline range and fuel tank with capacity for twenty days, nine-tube radio, sleeping accommodations for as many as nine, electric fans, linen lockers, embossed linoleum floor (easily kept clean), an extra wash bowl, medicine cabinets—and a peeper in the door to permit inspection of callers.

Once paid for, your trailer will cost you little except a slight increase in the gasoline consumption of your automobile. A. L. Clements, a Chicago manufacturer, bought a secondhand trailer. During a trip of 1,407 miles into the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee, which included 800 miles of mountain driving, he found it cost him $1.10 more a thousand miles for gas and oil when pulling his trailer. Where he averaged fifteen miles to the gallon without the trailer, his mileage dropped to fourteen with the unit attached to his car. His oil consumption remained the same. He averaged 350 miles daily, in ten hours' driving, including all stops.

In a recent test with a streamline trailer, built along airplane lines, Hawley Bowlus, the famous sailplane designer, actually increased his car's mileage more than three miles to the gallon. His 1,100-pound trailer eliminated the drag, or air suction, of the car by its streamline form. He achieved the "airplane effect" when he reached a speed of thirty-six miles an hour, when it felt to the driver as though the trailer had dropped off. In fact, many drivers told me they drive as fast with a trailer as without. On more than one occasion, trailers have followed in the wake of the towing car at speeds in excess of seventy miles an hour.

YOU will find your travel costs are just about what you make them. They depend, in part, on the distance you drive. Ralph N. Jordan and three relatives left Beloit, Kans., in August, traveled 7,100 miles through Nebraska, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, down the Pacific Coast, and back home through Texas two months later, in a trailer costing $325; they spent sixty-five dollars for gasoline and oil, $125 for food and twenty-five dollars on incidentals—a daily average, exclusive of the purchase price, of ninety cents per person.

Given a trailer, where can you park? The answer is—anywhere. Alongside the highway, on a country lane, at virtually any service station, or in one of the thousands of special parks for tourists.

In Washington, Oregon, and California alone, 1,000 trailer camps are now being prepared, a recent survey by the Automobile Club of Southern California shows. Camp operators are convinced "trailerites" are going to take to the road in droves. And they're getting ready to supply, at costs ranging from twenty-five to fifty cents a day, a level place to park car and trailer, with no backing out required; sanitary conveniences, shade trees, water, and service plug-ins so their visitors may have electric current.

Soon you will be able to roll out of your garage, no matter where you live, and find accommodation at the end of each day's journey. Trailer owners already have become gregarious. An average of 500 trailers daily were parked in San Diego, Calif., during the recent exposition. Again in California, forty or more trailers frequently take to the highway for a two-day mass picnic. Members of the "TravelOme Club," founded by R. T. Baumberger, who started building trailers as a hobby, take jaunts of 200 miles or more between Friday night and Monday morning.

ACROSS the continent at Sarasota, Fla., is the largest trailer park in the world. Last summer, 947 units were parked on its grounds during the annual trailer convention. Those attending last year's convention registered from forty-two states, plus the District of Columbia and four Canadian provinces.

Sociologists look on the tremendous increase in trailers as indicating a fundamental change in attitude toward the traditional obligations of home life. "It may not be amiss," said O. T. Kreusser, director of Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry, "to predict that if present trends in buying cars or buying homes continue, an increasingly large part of the population will live and carry on their home and business pursuits more around the automobile and less around a house as a fixed abode." Already, tens of thousands spend their winters in the South, migrating like birds to the North when spring comes, and living on wheels virtually the year 'round.

END

North American recreational vehicle manufacturers web sites are provided on Haw Creek in the RV categories of class A motorhomes and coaches, class B motorhomes and vans, class C motor homes, fifth wheel campers, travel trailer RVs, tear drop trailers, tent or folding trailers, and truck campers, including off road RVs. In most instances, along with the home page for the manufacturer, a list of available models is provided.

RV Manufacturers:

- Motor Coaches and Class A Motorhomes

- Class B Motorhomes and Vans

- Class C Motorhomes

- Fifth Wheel Trailers

- Travel Trailers

- Tear Drop Trailers

- Tent and Folding Trailers

- Truck Campers

- Off Road RVs

- Arkansas

- Montana

Contact Form at the Haw Creek blog