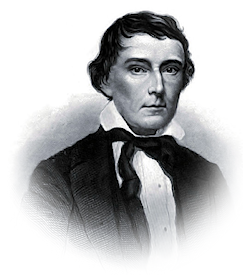

Alexander H. Stephens to ______[i]

Crawfordville [Ga.], Nov. 25, 1860.

Dear Sir: Your kind and esteemed favor of the 19th instant is before me, for which you will please accept my thanks. I thoroughly agree with you as to the nature and extent of the dangers by which we are surrounded, and the importance of united action on the part of our people in the line of policy to be pursued.

I know also that there breathes not a man in Georgia who is more sensitively alive to her rights, interest, safety, honor and glory than myself; and whatever fate befalls us I earnestly hope that we shall be saved from the worst of all calamities, internal divisions, contentions and strifes. The great and leading object aimed at by me in Milledgeville was to produce harmony on a right line of policy. If the worst comes to the worst, as it may, and our State has to quit the Union, it is of the utmost importance that all our people should be united cordially in this course. This, I feel confident, can only be effected on the line of policy I indicated.

But candor compels me to say that I am not without hopes that our rights may be maintained and our wrongs be redressed in the Union. If this can be done it is my earnest wish. I think also that it is the wish of a majority of our people. If, after making an effort, we shall fail, then all our people will be united in making or adopting the last resort, the “ultima ratio regum“. Even in that case I should look with great apprehension as to the ultimate result. When this Union is dissevered, if of necessity it must be, I see at present but little prospect of good government afterwards. At the North I feel confident anarchy will soon ensue. And whether we shall be better off at the South will depend upon many things that I am not now satisfied that we have any assurance of.

Revolutions are much easier started than controlled, and the men who begin them, even for the best purposes and objects, seldom end them. The American Revolution of 1776 was one of the few exceptions to this remark that the history of the world furnishes. Human passions are like the winds; when aroused they sweep everything before them in their fury. The wise and the good who attempt to control them will themselves most likely become the victims. This has been the history of the downfall of all Republics. The selfish, the ambitious, and the bad will generally take the lead. When the moderate men who are patriotic have gone as far as they think right and proper, and propose to reconstruct, then will be found a class below them, governed by no principle but personal objects, who will be for pushing matters further and further, until those who sowed the wind will find that they have reaped the whirlwind.

These are my serious apprehensions. They are founded upon the experience of the world and the philosophy of human nature, and no wise man should condemn them. To tear down and build up again are very different things; and before tearing down even a bad Government we should first see a good prospect for building up a better. These are my views candidly given. If there is one sentiment in my breast stronger than all others, it is an earnest desire for the peace, prosperity, and happiness which a wise and good government alone can secure. I have no object, wish, desire, or ambition beyond this; and if I should in any respect err in endeavoring to attain this object it will be an error of the head and not of the heart.

[i] From the National Intelligencer, Washington, D. C, Dec. 6, 1860, reprinting the letter from the New York Journal of Commerce, with a notice that it was addressed by Stephens to a friend in New York. Copy obtained through the courtesy of Mr. J. K. Smith, of Grand Rapids, Mich.

From Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1911.

Alexander Hamilton Stephens was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. After serving in both houses of the Georgia General Assembly, he won election to Congress, taking his seat in 1843. After the Civil War, he returned to Congress in 1873, serving to 1882 when he was elected as the 50th Governor of Georgia, serving there from late 1882 until his death in 1883.