March 30, 1861, Harper’s Weekly

The Crescent City

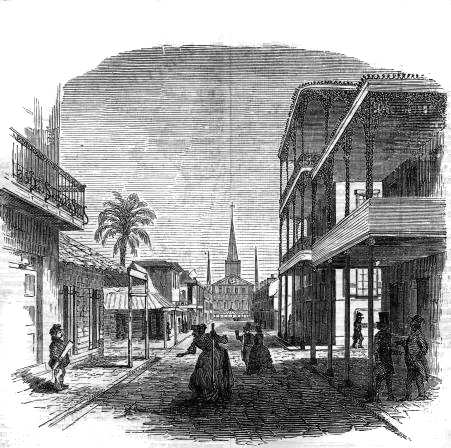

WE present characteristic sketches of the Crescent City. The traveler who approaches by the Pontchartrain Railway sees the domes, spires, and chimney-tops of the city peering over tufts of grass and shrubbery, looking as though a town had been sown there and was just coming up. Upon entering, one passes first through the French quarter, built up mainly of low red-tiled wooden houses, many of which are surrounded with shrubbery and ornamental trees. The lamps not unfrequently hang over the centre of the street, suspended by chains passing from one side to the other. Here the streets bear French names, such as “Rue des Grands Hommes,” “Des Bonnes Enfants,” “Dauphine,” “Bourbon,” “Toulouse,” “Bienville,” “Royale.” The shop signs are mostly French. “Artiste en Modes,” “Cafe des Quatre Saisons,” “Nettoyage de ‘fete,” ” Chambres garnies a louer,” and the like, meet the eye at every turn. French is the language commonly spoken by both whites and blacks, though the patois of the latter would be hardly intelligible in Paris. This excites the special wonder of their brethren from more northern States.

“The idea,” exclaimed Squire Berkeley’s Virginian servant, “of them black rascals undertakin’ to talk larned, like ladies and gent’-men!” His wonder was increased when told that this was their own language, and that few of them understood English. “I thought,” he said, “that all black people talked like we does at home. I thought they larned to talk from white people, and not outen books as these does.” That French could be learned without books passed his comprehension utterly.

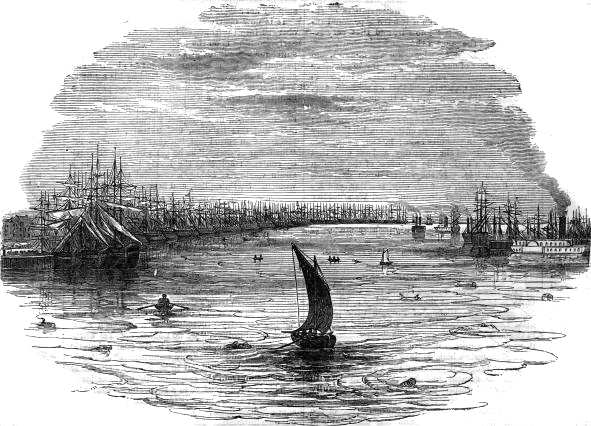

Approaching the river one finds himself in an American city; though even here the French element is not wanting, only not predominant. From the foot of Canal or Poydras streets, or, better still, from the upper deck of a steamer, one can perceive the peculiar conformation from which New Orleans derives its popular appellation of “the Crescent City.” The Mississippi, whose general course is almost due north and south, here makes a sudden bend, so that the city lies on its northwest bank, facing the southeast. Looking up stream, one sees a fleet of immense river steamers moored in tiers four or five deep; beyond them is a fleet of masts, fading away in the distance ; facing down stream, a similar fleet of steamers meets the eye; beyond them another line of masts, whose termination is hidden by the bend of the river. Eighty steamers have been counted at a time lying at the levee ;these, with fifteen hundred flat-boats from up the river, and three hundred vessels from other ports, American and European, which have often been in the harbor in a single day, give some idea of the immense commerce which centres at New Orleans.

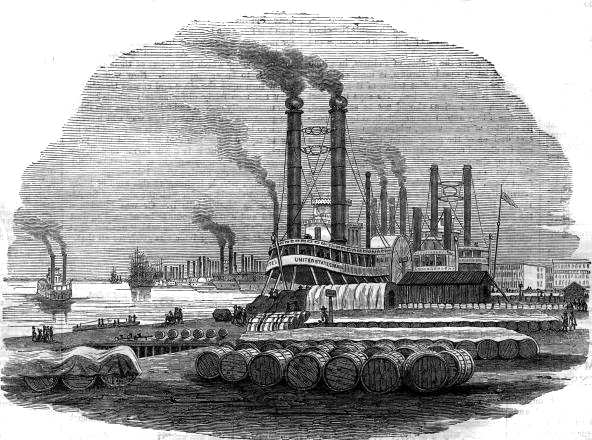

Looking shoreward, the levee presents a scene of bustling life altogether unequaled. The surface of the river, when it is full, is some feet above the level of the adjacent country. The levee is properly the embankment, beginning some 40 miles below the city, and extending about 150 miles above, built to prevent inundation. Opposite the city the levee is so broad as to furnish a landing-place for all the bulky merchandise in which the trade of New Orleans mainly consists. The broad space is literally buried under the wealth of the Great Valley. Bales of cotton, hogsheads of sugar, barrels of pork by the thousand, are arranged in long lines, piled up tier upon tier. Thousands of busy hands are engaged in loading and unloading, handling and removing this merchandise, whose volume, in the busy season, never appears to be diminished. There are cities whose entire commerce exceeds vastly that of New Orleans; but nowhere is so great an amount of commercial activity presented at a single view as on the levee of the Crescent City. The aspect of the levee at night is even more striking than by day. The fire-baskets on the bows of the steamers throw a red light over the scene, by the aid of which the stevedores and laborers pursue their work. In the back-ground, lit up by the ruddy glare, the spacious ware-houses and cotton-presses loom up, while in the distance the domes of the Odd-Fellows’ Hall, the Saint Charles, and the Saint Louis, and the church spires stand sharply out against the clear sky.

“Jackson Square” was the “Place d’Armes” in the old times. The Cathedral of Saint Louis, and the public buildings of the First Municipality front upon it. The Square itself is handsomely laid out, and is now the favorite resort of nurses and children. Of this we present a reduced sketch, also one of Lafayette Square.

The famous “Shell Road” is one of the specialties of New Orleans, It extends for about six miles back to Lake Pontchartrain. The road is built upon piles, by which it is raised a few feet above the swamp. Its surface is composed of the shells of a species of clam, of which vast embankments are found on the lake. These are ground down and packed together by the pressure of innumerable wheels and hoofs, into a compact body as white, and almost as firm, as solid marble. It furnishes one of the most delightful drives in the world.

The climate of New Orleans is as pleasant as that of any city in the world, and for nine months in the year is hardly surpassed in healthfulness. But during the other three months the pestilence, to which the unacclimated are exposed, drives away all who can leave, except those who are willing to run the risk of the fever for the sake of the comparative immunity which they enjoy when once acclimated. But in spite of the terrors of the sickly season, the population of New Orleans has increased with a rapidity excelled by but few cities of the country.

The Levee.

View in French Quarter.

Jackson Square.

Lafayette Square.