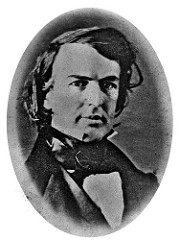

A likeness of Jones when he was editor and majority owner of the Daily Madisonian during President John Tyler’s administration.

An Essay.

By J. Beauchamp Jones, Philad.

The problem that all men are born with equal rights, has been settled by America in the face of the world–but that the Americans are endowed with all the intellectual attributes of the most favored of nature, time must discover, and conjectures for the future can only be based on the present condition of the people and the history of the past.

If distinct races are differently gifted, and various climates peculiarly characterized in a mental point of view, the Americans may claim all the advantages resulting from either, inasmuch as they derive their origin from the most cultivated nations, and the extent of their territory embraces every variety of climate.

But it cannot be denied that the European countries possess many advantages over our republic in the pursuit of letters. They have their ancient institutions of learning, wherein the wisdom of ages is collected; their professed authors, whose lives are devoted to literature; and their gentlemen of leisure, whose fortunes are acquired by inheritance, who naturally engage in the pursuit of literature and the elegant arts. These combine to maintain their enlightened position, and to facilitate their future advances. They have a “long start” of the Americans in the great race for national glory, and could mensuration as correctly set forth the destiny of states from premises palpable to all, as may be told the future revolutions of planets, calculated from the same infallible data which has invariably proved correct–then the prize would inevitably be to the strong and experienced, and the new fledged aspirants of our young confederacy would doubtless be “distanced.”

There are also other causes which might seem to indicate our present incompetency to contend with Europeans for the glories of literature. We are not only destitute of an ancient and romantic history, but also indisposed to cherish legends of the past. The great mass of Americans have their thoughts only on the future, and their struggles are for money rather than for fame. Originally destitute and discontented, and driven by persecution to a new world, they have hitherto been employed in the acquisition of those bodily comforts which the abode in a wilderness rendered so essential, and in framing a liberal mode of government to obviate all the evils endured in the country from which they fled. There still remain for the thrifty innumerable channels for the attainment of wealth in our vast uncultivated regions of productive land. Our commerce is also far from its acme, and thousands are reaping the profits of mercantile enterprise.

Thus, then, are we situated: With no classic institutions of former generations, no aristocratic classes possessing wealth and leisure, and but few who would barter their opportunities of accumulating riches for the precarious and often miserable occupation of an author. But the most powerful and withering cause which has operated against the chances of our country in the competition for literary honors, has been the piratical course pursued by our publishers, in reprinting the productions of foreign pens, because they could be procured without expense. This has not only been the means of disheartening many a native writer, but it has also promulgated European fancies and European sentiments, until many citizens of the republic have imbibed a partiality for foreign customs, and readily adopt the fashions of gorgeous courts. The periodical press was long indebted to the same sources for its matter, and whilst American contributors were neglected and discouraged, the fame of some British scribbler was either acquired or consummated on this side of the Atlantic.

Yet, notwithstanding all that may be said in favor of other countries, and to the disadvantage of America in the pursuit of literary renown, there is still a hope entertained by the Americans–a real or fancied star observed presiding over their destiny, in which they have implicit faith, and they continue to cherish the expectation, nay, determination, to rival in greatness all that is recorded of the most glorious nations. And the miraculous triumphs they have accomplished seem to warrant their most extravagant expectations. Weak in numbers, oppressed and reviled, America threw back the scorns, and redressed the injuries heaped upon her by the most powerful and haughty empire of the earth. She opposed her infant strength to the giant arm of a mighty kingdom which had crushed its foes for centuries, and trusting to the justice of that Being, who endowed all mankind with equal rights and immortal aspirations, she triumphed even in her inauspicious condition, and established a noble and happy form of government, despite the obstacles interposed by old and grasping monarchies, the absence of celebrated law-givers, and her apparent destitution of national resources. The penetration of statesmen and the experience of sages had asserted the impossibility of success; and yet the grand object of a diminutive, but determined band of men, was accomplished.

This era in the revolutions of the earth, serves to prove that the magnitude and power of the human mind, cannot be measured by mathematical calculation. The sea of intellect has not yet been fathomed–for each generation continues to usher into existence hitherto undiscovered regions. Neither are the mariners of the illimitable mental ocean confined to the highborn. The worldly poor and the worldly degraded, possessing the divine gift of mind, not unfrequently mount higher in the flowery fields of imagination, and penetrate farther in the intricacies of science, than those who have been reared amongst the ponderous tomes of time honored colleges.

When the mysterious and immortal ray of genius is implanted in the breast by the hand of the high priest of Nature, all other requisitions–the titles of inheritance, the academic lessons of learned masters, and even the smiles of cheering friends, are but secondary considerations to the predestined fortune of the recipient. Where was the line of kings from which Napoleon descended? Would it not have provoked a smile, had the plodding youth when but a humble subordinate, whispered his secret hopes and aspirations? And yet the spark which then but feebly flickered in his ambitious heart, ere long blazed forth the brightest sun in the military world. No circumstances can defeat the destiny of mind: chains cannot fetter it, nor can any power short of prescience prescribe its limits. The inspired bard of our father-land had no teacher on his loved banks of Avon but Nature, and yet his works have become the precepts of all learned doctors. Who can see the career of gifted minds? Who can say to our young republic, “thus far shalt thou go, and no farther.”

The history of America is before her. The account of her birth, and the vigor of her growth in the nursery, are yet only inscribed on the tablets of her history. What may be written in future, who can tell? That she is peculiarly favored of heaven, her herculean act of strangling the serpent of tyranny at her birth is conclusive evidence. What greater work of the intellect can be conceived, than the establishment of a novel and perfect system of government, embracing an immense continent and administering to the wants of many millions of people? And if America has excelled in arms, triumphed in legislation, and linked her commerce with every fruitful land, is it to be supposed that she will long remain indifferent to the glories of literature? She boasts her philosophers, her orators, and artists, whose names have reached beyond the confines of their country–and truly, but some half dozen authors–and thus there is a woful discrepancy in her literary reputation.

The Americans have hitherto been accustomed to look to England for literary aliment, and however pernicious the viands might prove which were set before them by the industrious caterers for public taste, yet they became fashionable, and their use almost universal. The American publisher could obtain every new work free of expense, and the prejudice once existing against the mother country gradually subsiding as our blessing increased, his shelves were relieved of their volumes by greedy purchasers, and thus his profits were made enormous, because no expenditure was required to keep his press in motion. Native authors could get neither smiles nor money for their labors. Foreign writers were lauded by mercenary critics, and read by the community, whilst American aspirants languished in neglect, until habit had nearly riveted the mental yoke of British bondage imperceptibly on the same people, who once rose in their power and defied the embattled hosts of the most warlike nation of the earth. Legislators feared to make enactments protecting our writers, under the impression, that the facilities of disseminating knowledge among the people, would be “too suddenly curtailed,” by arresting the piratical traffic in the productions of mind. So long had we luxuriated on the rich cargoes of free traders without the expense of freight or duty, and so long been accustomed to look in vain for a rivalry in similar wares amongst ourselves, that a senator from Pennsylvania openly avowed his fears, that should the authors of other countries be privileged to enjoy the exclusive advantages of their own property on this side of the ocean, and the rising generation be compelled to look to their own scholars for erudition, a dearth of intellect might ensue, which would be ruinous to our future welfare. In this manner did tories and old women argue, when it was proposed to destroy the tea in Boston. A slight sacrifice, and a resolute struggle, and the shackles of mind will be removed, as were the chains of oppression when we determined to be free! Although the law for the protection of American authors was doubtful in its origin, sluggish in its progress, and is still pending, yet its passage must now be inevitable, for the people have taken it under consideration, and their decision may be indicated by the recent change of the estimation in which Americans writers were held. The fiat of the nation will be for the encouragement of native authors, and before this generation shall have passed away, the complexion of our literature will be changed; genius will soar beyond the taunts of bloated sycophants, and not only receive its ample reward in worldly emoluments, but authorship will be considered, as it justly merits to be, the most exalted pursuit of man.

The change is now in operation. American authors, and American books, even now, are no longer the objects of ridicule abroad. Their merit is at length acknowledged in those countries most famed for talent, and American works are beginning to be re-printed and extensively circulated amongst those who have hitherto affected to jeer our impotence.

At home, we perceive a numerous and intelligent class of readers evincing a determination to foster native talent. Having in vain anticipated the passage of a law of protection, with a commendable public virtue which should be honored through all time, they have resolved to test the efficacy of the American mind, and consequently, the interminable talcs of German ghosts, and the nauseous productions of English epicures, have been almost simultaneously banished from our periodical press, and the rage for original contributions substituted in their place. The periodicals which persisted in furnishing their readers exclusively with stale re-publications, are now, (with one or two exceptions, and these are supported by resident foreigners,) amongst the forgotten things of the past, and those most successful are entirely composed of original matter. This is a change in our literary prospects of no ordinary import: it forms an era in the literature of America. From the great number of elegant magazines springing into existence, it is proven that we are a reading community; and from the decided favor now bestowed on native talent, it is seen that the sovereign people have espoused the cause of their own authors, despite the dilatory proceedings of their servants in congress. The voice of the nation will be for national writers, and the spread of republican principles; and those representatives who may persist in thwarting their desires will reap a nation’s censure.

The present is the most auspicious period for America to commence her literary career. Whilst the wounds of self-infliction, caused by the neglect to form a just copy-right law, are yet rankling and ere time shall make our habit of submission to Europeans in the grand efforts of mind a portion of our nature, the corner-stone of a noble structure might be laid, which the genius of the people should rear in future far higher than any has yet been done by the most cultivated nations. Conscious power will strain every fibre to prevent defeat by the artifices of the feeble. American writers, though laboring under continued poverty and neglect, have continued to struggle on. They have finally succeeded in winning the meed of admiration even from their rivals. And now, when the tide of popular prejudice, and the laxity of the laws which opposed them are being removed, and the mind indignant with the wrongs it has endured, and its energies roused to triumph over every obstacle, is the most fitting time for our authors to assert their claims for celebrity. They will have retribution for the injuries they have sustained; for the removal of the clouds which so long obscured them, will serve to display their light with ten-fold brilliance.

The time is approaching when the labor of the mind will as readily command its reward as the labor of the hands. Pens that have long remained idle, will be in requisition, and genius will cast its rags to be arrayed in robes. In the most prosperous states of antiquity, true greatness consisted in exalted wisdom and unblemished virtue. One giant intellect exercised more influence than a thousand stalwart men of ordinary faculties. Such will be the case in our country, and already has one president set an example for future rulers. Whatever may be the trusts reposed in the hands of literary men, by the president or the people, its safe keeping, and the faithful discharge of the duties appertaining, may be confidently relied upon. History mentions but few (if any) instances, wherein the meritorious aspirants for literary fame have proved wanting in manly integrity. The fruits of dishonesty can only be enjoyed by the recipient during his sojourn on earth. The true child of genius anticipates an eternity of enjoyment, and would not barter his interest in a future age for an empire gained by injustice, and maintained in blood, wherein his name would be buried in his grave, or only remembered to be exoriated. The man of gifted mind finds no interest in the fleeting sweets of the earth, but soars heavenward in glorious thought, cleaves the ethereal air beyond the eagle’s flight, scans with feelings of unmingled delight, the stupendous works of nature in the eternal cloud capped hills, the roar of the unfathomed ocean, or the revolutions of innumerable worlds, and bows in unfeigned adoration to the great Author of all.

Neither the glittering ingots of gold so much worshipped by the grasping, nor the flitting reward of intrigue and deception so much idolized by the politician, have any charms for the man of genius; for he possesses a world within himself of which no misfortune can bereave him, and which perishes not with the body. When his eye rests furtively on surrounding objects, and men pass by unnoticed, and sounds vibrate through the air unheard, the pallid brow is not the record of remorse, no the fixed abstraction the trance of stupor. The mind is busy with meditations unknown to the multitude, and the soul is exulting in the consciousness of immortality. He feels the link that binds him to another state of existence, where the prizes which men toil for on earth are unknown and valueless, save a good name, and he scorns the gauds that would tempt the short-sighted to leap beyond the bounds of honor. There is every reason for America to exalt her men of genius. They can neither stoop to peculation with a thirst for gain, nor be swayed by intimidation from the path of rectitude. Such alone are the pillars which must support our institutions through future ages.

America has not yet had a fair field, in the competition for literary laurels: but the consequence will be instead of defeat and despondency, a redoubled vigilance and an unswerving determination to excel. Had we contended on equal grounds, we should have submitted openly, had defeat been possible to Americans. But this has not been the case. What success could even an Irving, a Cooper or a Paulding expect, (to say nothing of those possessing extraordinary merit, but who from the suicidal course pursued in regard to a national literature, are without “a habitation and a name,”) when the works of a Goldsmith, a Scott and a Bulwer, were offered to the reader at the booksellers’ counter, for one third of the amount demanded for American books]

Yet foreign critics, not content with the vantage ground they possessed, (when driven from the assumption that “no one reads an American book,”) have directed their thunders against those amongst us who, from factitious circumstances, have obtained an ephemeral notoriety. After having in vain attempted to transfix the eagle with their malignant shafts, they would fain vent their enmity on the innocent butterfly. That an abundance of game may be found amongst us for their employment, there cannot exist a doubt: but that their efforts to destroy the gilded vermin, will be attended with injury to the country, is not in the most remote degree to be apprehended. Genius soars the higher, when the object of pointed scrutiny. But it cannot be denied that amongst us, as in all nations, the weak and the vain are to be found. A rich man may acquire more popularity from the perpetration of a few jingling stanzas, than a despised son of the garret shall obtain from volumes, containing the gems of divine thought. But the praise of the one ceases at the grave, whilst the name of the other lives after him.

It is a reliance on an unerring future, which inspires the child of genius to toil in obscurity. He relinquishes the prospects of immediate gain, in a total abandonment of every enjoyment, for some all-absorbing desire of the soul. Every power of the mind and body is exerted for the accomplishment of his grand object. Nor is his life, however degraded in the estimation of those more fortunate in the possession of wordly goods, bereft of every pleasure. The blurred walls of his wretched hovel sink before his sparkling eye, and his fruitive imagination calls into existence porphyry palaces of splendor, and his teeming fancy peoples them with appreciating beings who bow in reverence to his power. Ideal virgins crown him with rich chaplets, and a million voices salute him as the great master spirit. Thus it is why the author retires to commune with himself. Unfit to strive with the thrifty for gold, and finding no companionship in those who indulge not in inspired revery, he locks himself within his gloomy closet, and although hooted by the idle populace, yet is he enabled to unroll the scroll of the future, and enjoy in anticipation, the fame of his mighty works. Should his hopes never be realized, his pleasure is none the less: but there must be some secret assurance of reward, which induces a mortal to devote his life to the cause of letters, to neglect the smiles of fortune and endure the evils of poverty.

The oft repeated remark that “poets are always poor,” has become a proverb; and the profession of authorship, if connected with poverty, in the estimation of the money making community, is a disgraceful calling. The works of mind branded with disgrace! But it may be accounted for in the continued neglect of genius on the part of those who should patronize it, and its own unobtrusive character and unconquerable pride which revolts at the thought of solicitation. Authors are poor, and poverty a reproach. It remains for America to amend the evil. But a small portion of the money expended by the public for corrupt political purposes, would rescue every scribbler in the universe from starvation. Meritorious writers should be fostered: they cannot be exalted too high; nor will they repay the favors of their country with ingratitude.

The nature of a people is in some degree assimilated with the character of the country and clime they inhabit. America, with her territory fifteen hundred miles square, and her latitude varying from the soft gales of Arcadia, to the rude blasts of Russia, may boast a broader field for intellectual enterprise than any nation of the earth. Accustomed to viewing immense cities in every direction; beholding vast lakes and unfathomed bays; rivers, whose length surpasses any in the world; and interminable plains, whose dimensions the compass and the chain have not yet marked–the mind is naturally more expansive, than when confined within the limits of a narrow state or island, where the eye takes in at one glance nearly the whole penfold of a monarch’s clustering subjects.

Each citizen of America is one of the supreme lords of the land. He journeys for days and weeks, and whithersoever he places his foot, he may exclaim, “This is my country.” No tyrant dare confront him, and he proudly feels the blessings of liberty. Every one then, enjoys an interest in the confederacy. Whilst the aristocrats who have their titles and wealth at stake in Europe, constitute the only class willing to exert themselves for the perpetuity of established institutions, and the accession of governmental power, in America, every individual exults in the glory of his country, and would freely die to maintain its honor. The whole nation is desirous of national renown, and every man is willing to contribute to its acquisition. Thus, whilst but a select few may hope to win military or literary laurels in regal governments, our republic opens the lists for every man. Nor is it without a possibility of success that the humblest and most obscure join in the competition for literary fame, as well as for martial glory. An inscrutable Providence makes no distinction in the gifts of mind: nor is the wealth of intellect inherited like kingdoms. If the laborer’s son is deserving, he is born to the privilege of being a president. We have no distinctions but those of the heart and mind. The man, and not his occupation, is the standard of respectability. The prospects of all are equal, and the efforts of each enhance the prospects of the nation.

There is not a lyceum in this fair city, but performs a service to the country. The poorest mechanic may shed lustre on his native land. He may command armies, preside over councils, or confer benefits on future generations by the blessings of wisdom. It matters not what may be his trade, nor what the condition of his purse: if heaven has touched his heart with one glimmer of genius, he may surmount every obstacle. The want of academic tutors, and the absence of the ten thousand gilded volumes unread in the rich man’s library, need not deter him. Nature “is mighty and can prevail.” Even in the land where rank and wealth combined to crush the hopes of honest poverty, the genius of a Burns inscribed his name in living letters, which will be read until the language expires. But in this land the meritorious need not look to the beneficence of the great for reward; they have the bestowal of honors and emoluments in their own hands, and the highest in office is dependent on their favor. The poor form a majority in all countries, and where the multitude is ignorant and debased, the supremacy of the laws can only be maintained by the sword. Thus citizens sink to slaves. But when the humbler classes are impressed with the value of knowledge, and often meet to make interchange of thought, to sally together up the delightful heights of science, or gather perenne roses in the inexhaustible fields of poetry; men rise almost to gods, and neither traitors nor tyrants will ever attempt to enslave them.

The ancients would never have degenerated, had such men as Socrates and Cicero been cherished. But in that evil hour, when the best friends of the state were doomed to death, the curse of ignorance, and its attendant despotism, seized upon the people. The poison which passed the lips of Socrates penetrated the vitals of Greece, and the axe that fell upon the neck of Cicero, severed the head of Rome.

The superiority of mind over every other possession of man, is sufficiently proven by the endurance of its works, after every other vestige of his being is swallowed up in the yawning gulph of oblivion. The crumbling columns of the Pantheon speak the skill, but not the names of the artisans who wrought them. Mighty heroes have risen, and after brandishing their gory swords a few brief years, have returned to dust, to be no more remembered forever, whilst Cicero’s fearless accusation of Catiline in the senate, and even the gentle Pliny’s account of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, are still the subjects of universal admiration.

1 Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine and American Monthly Review, Volume 5; November 1839, pp. 267-270. (Burton’s was edited by William E. Burton and Edgar Allen Poe at this point.)