“The bombardment which we had so long expected came upon us at last almost as a surprise. “

First Scenes of the Civil War

By James Chester1, 2

In April 1860, James Chester was a sergeant in Battery E, 1st U.S. Artillery Regiment, stationed at Fort Sumpter. Twenty-four years later, his reminiscences of the events at Moultrie and Sumter as a senior enlisted man were published in The United Service, A Monthly Review of Military and Naval Affairs, where he limited himself “strictly to what I find in my memory, facts, and impressions the recollections of which have withstood the erosions of almost a quarter of a century.”

Note: Images in this article are from various sources. The original article in the 1884 issue of The United Service had no images.

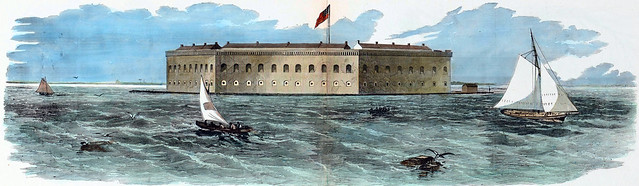

Fort Sumter, Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, 1861.3

Fort Sumter, Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, 1861.3

(previous) Work and sleep were the sole occupations in Sumter. There was no idling and no amusements. The work was hard and the workmen few. In heaving and hauling the men soon learned the value of a song in securing combined effort. The favorite song was one having the refrain, “On the plains of Mexico.” We had rigged a shears, and with an improvised capstan walked the guns from the parade to the terreplein (a hoist of fifty feet) as an accompaniment to the favorite songs. There was one party hoisting and another mounting guns. It was my lot to have charge of the hoisting party. We sent up all the lighter guns first. They consisted of 32- and 42-pounders and 8-inch columbiads. At last we came to the 10-inch guns. We considered them monsters in those days. We only had three of them in Sumter. They weighed about fifteen thousand pounds each. There was some doubt as to the strength of our tackle, but no better could be had, and we took the risk. The first 10-inch went up finely, and the second nearly so. It had reached the desired height, and nothing remained to be done but to swing it in on the terre-plein. I had given the word, “Avast heaving!”— the use of nautical terms must have been suggested by the song, —and ordered three men up to man the watch-tackle. The others remained below. At the very first pull on the watch-tackle the strap on the upper block of the fall parted, and down went the seven tons of iron. I felt faint for an instant, believing that a hole was made in the garrison; but when at last I looked over and saw the men standing around, astonished but unhurt, and the gun erect, as if set for a sun-dial, in the midst of them, and buried to the trunnions, I experienced a feeling of relief which almost brought the tears to my eyes. Very fortunately, in anticipation of some such accident, a new block had been prepared, and we soon re-rigged the fall, and sent No. 2 up to the same old song without further accident. No. 3 was mounted as a mortar on the parade.

Judging from the quantity of flagstones on hand, it must have been the intention to pave the parade with them. They stood on edge in long columns, and almost covered half the interior space of the fort. It was necessary to remove them, if for no better reason, to give us room to work. So they were carried and piled up in front of the lower tier of casemates, closing them as high up as the spring of the arch. This was a doubly fortunate arrangement. It left the parade a bare sand patch, capable of receiving with the least possible danger all the mortar shells the rebels might choose to throw into the fort, and it effectually protected the men in the lower casemates from splinters.

There is very little danger about a mortar-shell exploding in sand; it penetrates to such a depth that when it bursts it acts exactly like a mine. An amusing illustration of this occurred during the bombardment. It was night; the first day’s bombardment was over, except that the rebels kept stirring us up with an occasional mortar-shell. This they kept up all night. Somebody had discovered a little rice; it had been damaged by salt water and spread out-perhaps by our predecessors—in an upper room to dry. It was now full of sand, dirt, and broken glass; but it had been scraped up and cooked, and some of the men were straining it through their teeth, and apparently enjoying it. One man, a tailor, who belonged in the magazine on the other side of the work, concluded that his comrades over there might like some of it, so he heaped a lot on a tin plate and started. To reach the magazine in safety involved a long journey round the batteries, which were now in perfect darkness. Across the parade the journey was comparatively short and entirely free from obstructions, and the shells were coming less and less frequently. He determined to cross the parade immediately after the next shell. He had not long to wait; a shell came and burst in due course, and Carroll started with his rice. He had got about half way when that unmistakable whizzing which indicates the approach of a mortar-shell fell upon his ear. It must have been fired before he left the casemate. He halted a moment, glanced upward, and sure enough the fiery messenger was after him. He instantly took to his heels, but hardly had taken five steps when the shell struck right behind him, and immediately burst. Nothing was seen for a few moments but a volcano of sand mixed with fire. We all thought the tailor’s goose was cooked, but we were wrong. Presently we saw him gather himself out of the sand and streak it toward the magazine like a scared dog. When he reached safety, out of breath and almost out of mind, he gasped out his grievance, which simply was, “ I’ve lost my rice! I’ve lost my rice!” That he had got away safely, without loss of life or limb, did not seem to impress him.

The bombardment which we had so long expected came upon us at last almost as a surprise. It was about half-past three in the morning. A steamer approached and fired a gun. That was the signal that somebody on board desired to communicate with the fort. A boat was sent out, and brought back the notification that General Beauregard would open his batteries on Fort Sumter in two hours. The major was still abed, and, so far as I know, did not get up immediately. He ordered that the flag be hoisted, and that the men remain in bed until the usual hour for reveille. The flag was sent up, and the news spread rapidly among the men. Few remained in bed, although perfect quiet was maintained until the drum announced that it was reveille. As the hour for the opening approached, I stole up on the ramparts to see the first shot fired. It was a damp, raw morning, and intensely dark. Lieutenant Jefferson C. Davis was up there, on the same errand as myself. We hadn’t long to wait. Promptly at the appointed hour the first shot was fired. It was a mortar-shell, and very well aimed. I traced its course, which the burning fuse enabled me to do, from the mortar, about two miles away, until it burst inside Sumter. The rebel batteries then opened on every side. It was a grand and fascinating sight. In the pitchy darkness the flashes of the guns looked like lightning; and it required but little imagination to convert the screaming shot and hissing shell into infuriated fiends darting through the murky air. The mortars were admirably aimed; the guns were shooting high. Of course the gunners could not see their object. They were aiming by marks previously made on the carriages. As daylight appeared the grandeur of the scene faded out, and the danger of it became apparent; and we sought shelter in the bombproofs. For two hours the rebels had the battle all to themselves, and the Sumter garrison spent the time in studying effects. By the time they opened in reply, they had got used to the racket, and had come to the conclusion that the reality of war was tamer than the anticipation.

Reveille sounded on the morning of the bombardment at the usual hour, as if nothing extraordinary were going on. The men were paraded under the bomb-proofs and the roll was called. The usual time was then devoted to folding bedding and cleaning up barracks, and those who had an appetite that way had an opportunity of enjoying a little artillery pork,—so called on account of its rusty facings—by way of breakfast. Assembly then sounded, the men again paraded, and the orders of the day were announced. The tour of duty at the guns was to be four hours. There were two reliefs, consisting each of one company of artillery, a few of the band, and some workmen. Battery E having the senior captain was the first for duty. It was divided into three parties. The captain took immediate command of the first, and marched it to the battery bearing on Morris Island. Lieutenant Davis, the only other officer with the company, marched the second party to the battery bearing upon Fort Johnson and the James Island batteries. The third party was marched by myself to the guns bearing on Fort Moultrie, the Sullivan’s Island batteries, and the ironclad floating battery, which was moored close to the Sullivan’s Island shore. Very soon after fire was opened, the post surgeon, who for some time had been doing line duty, joined the third party, and was the only commissioned officer with it throughout the bombardment.

Sumter opened fire about 7.30 A.M., the first shot being fired from the captain’s battery. By this time the sun was well up, and the enemy’s batteries were fairly visible, although surrounded by a bank of smoke from their own guns. I soon found out that the theory and practice of gunnery were by no means identical. The rays of light were so refracted by the smoke bank, that gunners trusting to their eyes alone invariably shot over. Fortunately, I had prepared all the guns for night firing, in advance. Each gun had been carefully pointed at every prominent object which it might become desirable to demolish within its field of fire, and the position on the traverse circle of a pointer screwed to one of the chassis-rails distinctly marked with the name of the object. On the breech of the gun a scale of elevations was painted and marked in a similar manner, the elevation being given by setting a short iron rod in a socket in the cheek of the carriage, and elevating or depressing the gun until the other end of the rod, which was shaped like a chisel, was at the desired mark. Resort was had in the battery with which I served to this night-firing device, and it worked admirably, giving steadier results than I think could have been obtained with the breech sight, on account of the refraction, which was constantly varying. There was little excitement among the men. They worked their guns in a steady, business-like manner, and the marksmanship was fairly good; but Fort Moultrie and the ironclad floating battery were very unsatisfactory targets. We could see our shot bouncing off the iron battery like peas, and Fort Moultrie was so buried in sand-bags as to be almost invulnerable. We were about evenly matched in this respect. Sumter was suffering no material injury, and if the men were reasonably careful, they were as safe as they would have been in New York.

The major having determined to man only the lower tier of guns, we were compelled to the exclusive use of solid shot. Our shell guns were all mounted en barbette on the third tier, and many a grumble was indulged in by the men, in a quiet sotto voce way, at their not getting a fair show with the Johnnies. They instinctively felt that they were doing no injury to the enemy. They were only throwing solid shot with more or less accuracy into a sand-bank, or against the impregnable sides of iron batteries. It was all very beautiful and noisy, but it failed to come up to the expectations of the men. It was not what they thought war should be. These feelings prompted the commission of an act which no one, not even the perpetrators, would care to justify, but which, being attended with no serious results, everybody can afford to laugh at. Of course no officer knew anything about it.

A large crowd had collected on the Sullivan’s Island beach, out of the line of fire, to witness the duel between Moultrie and Sumter. They were rebels, no doubt, but, so far as we knew, they were non-combatants. Our men, however, were too hungry and too angry to recognize any fine shades of difference. So, after making sure that no officer was around, they trained two 42-pounder guns on the crowd, and fired. The first shot struck the edge of the water, perhaps thirty yards in front of the crowd, and, bounding over their heads, went crashing through the Moultrie House, a large summer hotel from which floated a yellow flag. The second followed a similar course. No damage was done to the crowd,—that is, no physical damage; but you ought to have seen that crowd run.

Another incident, prompted by the same feeling, was justifiable as well as amusing. For four hours we had been pounding away at Stevens’s battery and making no impression on it. This was very annoying to the men, and doubtless equally so to the officers. The non-commissioned officers believed they could demolish the battery with the 10-inch gun. The 10-inch gun referred to was mounted en barbette on the third tier, and the major had ordered that no guns on that tier should be manned. Orders were sacred in the opinion of Tom Kernan, but the demolition of Stevens’s battery was a duty. In this case duty and orders seemed to conflict, and Tom was troubled. Tom was an old sergeant, a veteran of the Mexican war. In his dilemma he consulted with the ordnance sergeant, another Mexican war veteran, and they agreed that if it could be done on the sly, under the circumstances, the major’s orders might be disregarded. They would not however, take anybody with them. The blame, if any attached to the act, should rest entirely on their shoulders. Consequently they watched their chance, and when the major was out of the way, slipped up-stairs to the barbette battery.

The gun was already loaded and aimed at the very battery they desired to strike. For weeks before the bombardment began all the guns were kept loaded. They had nothing to do, therefore, but slip in a friction primer in the vent and pull the lanyard; this was the work of a moment. The gun was fired, and the two sergeants and those below who were in their secret, watched the flight of the shot with almost painful interest. It missed-missed, seemingly, by a hair’s breadth just grazing the top of the battery. Great was the disappointment. So much risked; so little won. But the two sergeants would not give it up so. They might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb. They were determined to have another shot. The gun was reloaded, which was quite a feat for two men, as the shot weighed one hundred and twenty-eight pounds; but when they tried to run the gun “in battery” they failed. It required six men to throw the carriage “in gear,” and the two sergeants could not accomplish it.

Although the discharge of the 10-inch gun had escaped the observation of our own officers, it had been noticed by the rebels. They knew all about the position and power of that particular gun, and had no doubt wondered at its silence. Now that it had opened it was of the utmost importance that it be silenced at once; so every rebel gun that could be brought to bear was turned on it, and a shower of shot and shell came hissing and hurtling about the ears of the two sergeants who were still tugging in vain at the handspikes.

Matters had now reached a crisis. “By Gemini,” said Sergeant Tom, “let us fire her as she is.” It was the only thing they could do. So the elevating screw was given half a turn, the primer was inserted, and the ordnance sergeant ran down to see if the coasts were clear. Meantime, Tom, who was left holding the lanyard, found himself in a tight place. Shot and shell were coming thicker than ever. The rebel gunners were just getting the range. Tom was lying down because, as he said, there was no room for him to stand up. What could be keeping his friend so long? Traverse circles were being torn up by the enemy’s shot, and great blocks of granite were slashing about the terre-plein. He could stand it no longer; the lanyard was pulled, and the shot struck the battery, and seemed to do considerable damage, but the gun having been fired out of battery recoiled over the counterhurters and turned a somersault backwards.

As the ordnance sergeant reached the top of the stairs he met the 10-inch gun going in the opposite direction, and, looking around for his friend, discovered him hugging mother earth half dead with fright,— not at the enemy’s shot, but at having dismounted the boss gun of the outfit. Both compatriots came down. There were now additional reasons for keeping mum about the 10-inch gun; and the major never learned how it was dismounted.

An incident occurred during the first day’s bombardment which has been misinterpreted by many writers. When the fleet made its appearance off the bar, which it did soon after the bombardment began, Sumter saluted it by dipping the flag. Just as the flag was making the third dip a shell burst near the staff, and a fragment cut the halliard. The flag, of course, ran down, but the halliard being swollen on account of the dampness, and rather kinky, jammed in the pulley, and the flag could neither be hauled up nor down. It remained, therefore, at halfstaff. Upon this foundation the story that Sumter made signals of distress was built. Sumter made no signal of distress; the position of the flag was an accident.

The rebels had the satisfaction of shooting down our flag during the bombardment. A solid shot struck the topmast a little above the cross-trees, and down it came. A dozen men were around it in an instant. The flag was disentangled from the débris, a pole was procured,—the old topmast was too heavy to handle,-and the flag was nailed to it. About half a dozen soldiers then carried the new staff to the parapet and lashed it to a traverse made of spare gun carriages. When the little party appeared on the parapet the rebels turned every gun upon them, and cannon-balls bounced about them like peas thrown by the handful. Yet not a man flinched, and none were hit. It was a gallant deed and nobly done; but I am not aware that any soldier claimed special credit for it; it was their duty, and they did it, and history has not preserved any of their names. Bringhurst, a young Philadelphian, is the only one of the party whom I distinctly remember. He was conspicuous. It was he that nailed the colors to the mast, and I saw him at the post of danger on the parapet lashing the flag-staff to the gun-carriages. It gives me special pleasure to record the facts in this case, as all the glory and rewards were given to another man, a civilian, who had been permitted to come to Sumter to look after Major Anderson after taking an oath to the South Carolina authorities that he would in no way assist in the defense.

The night after the first day’s bombardment was one of suffering and anxiety. It was very dark, dreary, and cold,-at least I thought so. The presence of our fleet off the bar added to our anxieties, and increased the responsibilities of the guard. The rebels might storm us. The fleet might send us relief. Both would come in boats. Both would answer in English. Both, perhaps, would say “Friends.” I can only judge of the feelings of others by my own on that night of hunger and misery. I had charge of one side of the work—the Moultrie side—from eight to twelve o’clock, and I never knew how long four hours really were till then. I knew the men were tired, and yet I had confidence in their vigilance. But, if any party came, the decision as to its character and reception must be promptly made. There would be no time to refer the question; every moment would be precious. So I crawled into an embrasure from which I could see seaward and Moultrieward at the same time, and made my mind up to accept the direction from which any approaching party should come, as primafacie evidence of its character. If the rebels had sent a storming-party that night, and had approached my side of Sumter from the direction of the sea, they would have had the benefit of every doubt until the very last minute.

My position in the embrasure was not comfortable, but I made the best of it, resting my head on a cast-iron acquaintance which shared the vigil with me. My cast-iron friend had the advantage of me. She was loaded with a double charge of grape and canister, and I was empty. I had forgotten my hunger during the day, but during those quiet hours of the sleepless night my appetite came back like a raging demon. It seemed to be eating up my viscera, and I could bear it snarling and worrying over the repast like an angry dog. And then the cold, or the ague, or a touch of both, made my teeth chatter till I bit my tongue. There was no danger of going to sleep. And my condition was no worse than that of my comrades. I have described my own, merely as an illustration of theirs. But midnight came at last, and I was relieved, and the doctor gave me a spoonful of brandy which did me a power of good. I slept after it like a top.

The second day’s work began pretty much as did the first. We had not been disturbed during the night by either enemies or friends. We were none the better pleased at that, and I heard some bitter things said about the fleet. But the pounding proceeded with as hearty goodwill as ever. Early in the day we discovered that the quarters were on fire. We put it out. Then fire broke out in another place. We put that out too. Then fire broke out in several places at once, and we found out what was the matter. The rebels were firing red-hot shot. We let the buildings burn.

The quarters at Sumter were supposed to be fire-proof,—that is, they were built as fire-proof buildings,—but they burned up all the same. That they burned badly was not due to their fire-proof character, but to the fact that they were wet. Our cisterns consisted of immense iron tanks under the roof. These had been riddled during the first day, and the water had escaped and saturated everything below. So the quarters smoked and sizzled, flaring up here and there into a flame, whenever the fire found a dry place.

As the fire approached the magazine we had, of course, to close it, but we kept it open to the very last moment. We had a couple of tailors at work in the filling room making making cartridge-bags out of soldiers’ shirts, and every available material. They remained at their post until driven out by the smoke. Even the powder-chamber of the magazine was full of smoke before the doors were closed. To continue the bombardment until the magazine could be reopened, a number of barrels of powder were taken out, I think nearly a hundred. These proved to be an elephant on our hands. The fire-proof floors began to fall in, and showers of sparks were scattered about and drifted into every corner of the casemates. There was no safe corner which could be used as a temporary magazine, and the powder-barrels had to be covered up with wet blankets. There were also lots of loaded shells which had to be covered, and there were not blankets enough to go round. When the last blankets had been utilized there were still some thirty barrels of powder to cover, and they had to be thrown out at the embrasure.

That the rebels were watching Sumter closely is evidenced by the fact that they discovered the discharge of powder-barrels from the embrasure almost immediately. That they knew what they were may well be doubted. Nevertheless they turned their guns on them all the same, and very soon produced an explosion. Although several men were near the embrasure at the time, no one was injured; in fact, they knew of the explosion only from the fact that the gun at that embrasure was blown from battery. The explosion did no damage whatever.

At this time the smoke inside the fort was as thick as wool; it was like the darkness of Egypt; it could be felt. No man could breathe standing up. The fire of the fort had been reduced to one shot in five minutes. It might be many hours before the magazine could be reopened, and it was necessary to husband our ammunition. Meantime the rebel batteries doubled their fire. Shot and shell were screaming and crashing around. Occasionally a salvo of explosions told us that the fire had reached some of our grenades. The magazine was now enveloped in flames, and the fire, having found abundance of dry material around the magazine corner, shot upwards to the sky great tongues of flame, which helped to clear the smoke away a little, and gave us a chance to breathe. But the danger was imminent. That the magazine would blow up was more than likely. From the major’s actions I think he had no doubt on the subject. I think he wanted to die in the midst of his men. He called them around him, informally, to be sure, and without any reference to the anticipated explosion ; but there was a solemn dignity in his voice and bearing which could not be misunderstood. There he stood, in the midst of a little group of dirty-faced men, wrapped in his military cloak, and waiting. It was a grand tableau. The rebel batteries were pouring in their shot faster than ever, and the major remarked, “Beauregard is behaving like a brute.” No one replied. The men knew his feelings about the war, and admired his fortitude all the more.

We still kept firing at five-minute intervals. It became the duty of my battery to fire the next gun, and I withdrew from the major’s group to see that it was done. The gun was a 32-pounder. It was already out of battery, and as No. 1 approached the muzzle to sponge out he discovered a face looking in at the embrasure. No. 1 was a soldier named Thompson. The smoke was still very thick, and from my position I saw nothing; but I could hear a somewhat excited conversation going on, the only words of which that I caught were, “For God’s sake, don’t make me stay here and be killed by my own shot and shell.” I then drew closer to the embrasure, and saw Thompson dragging a man in by the hand. The man was in citizen’s clothing, was very much excited, and some of us thought drunk. He asked for Major Anderson, and one of the men went to find him. The major soon appeared, stately and solemn as I had left him a few minutes before, with his cloak still wrapped around him. He said, addressing the stranger, “To what am I indebted for this visit?” The stranger replied, “I am Colonel Wigfall, of General Beauregard’s staff. For God’s sake, let this thing stop; there has been enough bloodshed already.” To this the major replied, “There has been none on my side; and besides, your batteries are still firing on me.” Wigfall then

turned towards Thompson, who, I now observed, had a white handkerchief tied to something (I think a sword, but will not be certain), and said, “Wave that,” pointing towards the embrasure; then, turning to the major again, he said, “I’ll stop them.” Meantime Thompson banded the white flag to Wigfall, and said, “Wave it yourself.” The absurdity of any such proceeding then seemed to dawn on him: the handkerchief could not be seen twenty feet away. He turned to the major, and, holding out the handkerchief, said, “Will you have somebody show this above?” pointing upwards, and evidently meaning the parapet. The major answered, “Yes, to oblige you; but let him take something that can be seen.” The surgeon, who, I think, was present during the latter part of the conversation, provided a hospital sheet to exhibit. One of the men carried it to the parapet, and the major and Colonel Wigfall, and officers of the garrison, retired into a casemate which had been fitted up as a hospital.

The white sheet was shown, I suppose, as the firing ceased in a very few minutes, and sentinels were posted immediately. The men very generally jumped out of the embrasures, and were impressed, perhaps for the first time in their lives, with the magnitude of the blessing of fresh air. They sat around on the rocks, like coal miners who had just come up the shaft from a very deep mine. Very little was said. Occasionally one would ask, “Who is Wigfall, anyhow?” or “How in — did he get here?” But as a rule they were not inclined to conversation.

Presently a small boat put out from Sullivan’s Island, and pulled for Sumter. It had no white flag, consequently when it got within musket-range it was warned off. It then displayed a white flag, and was permitted to land. We could no longer indulge in the formality of sending a boat to meet it. We had no boats. Those we had left outside were riddled with shot, and those we had taken in were burned up. The small boat contained three very indignant Confederates. One of them was Stephen D. Lee, formerly a lieutenant in the Fourth United States Artillery. Of the other two, one was named Ferguson, also an ex-officer of the United States army. The third was unknown to me, and I did not learn his name.

On landing, Lee was the spokesman. I do not remember who received him; it was the officer of the day, whoever he was, and I think it was Dr. Crawford. Lee said, “What does this mean?” referring to the action of the sentinel I suppose. “Has not the fort surrendered?” The officer of the day made some reply; then Lee said, “What does the white flag mean then?” I did not catch the reply, only I heard the name of Wigfall mentioned. Meantime Major Anderson approached, and the rebel officers addressed themselves to him. There was quite an animated, not to say angry conversation between them, the words of which I would not pretend to record. The purport of it, as I understood it from the fragments which reached my ears, was that the new arrivals repudiated the action of Wigfall. Then I remember the major’s words, because it required an effort to keep from cheering. They were, “Well, gentlemen, you can go back to your batteries; I didn’t send for you.” They didn’t however go back right away, but all went into the hospital casemate. What transpired there of course I do not know. This was between two and three in the afternoon.

In the course of half an hour our rebel visitors took their departure, but the firing was not resumed. The men were instructed to remain by their guns, and be ready to resume the action at any moment. The situation was then discussed by the soldiers from their stand-point of utter ignorance of the nature of the negotiations which they believed were going on. That the rebels had got something unpleasant to chew on, and that the garrison was not going to be surrendered as prisoners of war, were accepted as facts fairly deducible from the circumstances, and gave great satisfaction. As sunset approached the men became more and more convinced that the fighting was over. That they could ever conquer in such an uneven contest was hopeless from the first. That they should be surrendered as prisoners of war within sight of the national fleet was held to be very unlikely. That they would get away somehow, was the main solution of the problem. Either the fleet would send boats for them after dark, or their own boats would be patched so as to float, and they would drop down with the tide. That they would not only be permitted to leave, but furnished with transportation, was never dreamed of.

But the men were not all optimists. There were some who took a gloomy view of the situation. The various little groups of threes and fours which had gathered outside the fort, where fresh air was to be had, to discuss the situation were a study for a painter. The men were hollow-cheeked, cadaverous, grimy. Some cursed their luck, and some the fleet, and some the enemy; but nowhere did I hear the word “surrender.” Haggard, hungry, and hopeless, with heartless enemies without, and gaunt starvation, fire, and smoke within, so far as they knew abandoned by their government and forgotten by their country, yet no disloyal word; and they were only enlisted men. Can history furnish an example of greater devotion?

At dusk another small boat bearing a flag of truce approached from Sullivan’s Island, and the men felt that a decision upon the pending proposition had been reached. They soon learned that the fighting was indeed over, and that the garrison would be transported to the fleet next day. No surprise was expressed by the men. That they would make their way to the fleet by force or stealth was the solution they had already reached. That they were to go there peaceably was only a slight variation. They were content.

Still another night in Sumter, only less miserable than the last. The barracks were still burning. Blankets were still in use as coverings for loaded shells, and the men had to shiver through the night on the bare stones of the batteries. But morning came at last, and brought with it the bustle and preparation for departure. The men were lighthearted; they would leave Sumter without a single regret. So far as comfort was concerned, Sumter had nothing left. It was a ruin, and the men were jolly over the prospect of leaving it. Their recent unpleasant, not to say dangerous, situation already seemed a long way off. They had got a small glass of brandy each from the surgeon, and it had loosened their tongues. They were particularly hard on one young soldier who had a presentiment that he would never leave Sumter. He was a brave young man, and did his duty nobly. He was the sentinel that held the fort at Moultrie while it was burning, but he had, or at least said he had, this gloomy presentiment, although he was cheerful enough all the time, and the men remembered it. So they bantered him about it now that the battle was over, saying, “Well, Galway, you weren’t killed after all.” To this he would reply, “I ain’t out of Sumter yet.” He stuck to his presentiment. And he was right. He never left Sumter; his body lies buried there to-day.

The old flag, tattered and torn, which had floated over us during the bombardment, had been shot down, nailed to a new mast and reraised, and which still floated over us, was to be saluted with a hundred guns before it was lowered into the arms of its defenders. It was now prepared for the ceremony. The nails were drawn, and halliards were rigged to the improvised flag-staff. In the salute every serviceable gun that could be manned was to be used. Twelve guns were prepared for the purpose, eight in the lower, and four in the upper tier. The upper-tier guns were those on the sea-face of the fort. The salute began below. Eight shots were fired from the lower tier, then four from the upper, and so on. It was deliberate and with full charges. An officer and two or three men stood ready to receive the flag in their arms as it descended when the last shot was fired.

The handling of powder, especially on the upper tier, was rather a risky business. The fort was still on fire, and every discharge would be likely to liberate a shower of sparks, as the tottering walls trembled responsive to the vibration. We had no budge-barrels, and no really safe place to put the cartridges. As the safest convenient place they were placed under a lean-to bomb-proof, constructed of heavy iron embrasure-plates, which the men called a “dodging-hole.”

The salute proceeded without accident until the forty-eighth round, which was fired from the last of the upper-tier guns. As it was fired, the second gun on the upper tier was discharged prematurely. Either the gun had been carelessly sponged, or sparks had blown into it as the cartridge was inserted. I was standing on the parapet near the third gun at the time, and turned to see what had happened. I did not see right away. A second explosion took place which fairly raised me off my feet, and I fell, dazed, but not stunned, on the parapet. I jumped off the parapet, partly for safety and partly to see what damage had been done. The smoke was very thick, and as it cleared away a sad sight presented itself. No. 1 cannoneer(a)(b) xxxxxxx, at the gun which exploded prematurely, was killed. He had never known what killed him. Half his head was blown away. No. 2 was fatally injured xxxxx(Edward Gallway),—he was the young man who had the presentiment. No. 2 at the adjoining gun was also seriously hurt. He was burned black in the face, and lay covered with the heavy iron plates of which our temporary magazine had been constructed. He still breathed, but there were slight hopes of his recovery. Five or six more were wounded more or less severely. The accident terminated the salute at the fiftieth round, two guns having been fired after the explosion from the lower-tier batteries.

The wounded were carried down to the parade and laid on the ground, and the surgeon attended to their injuries. In about half an hour Galway died. The body of the man who had been instantly killed was also brought down and laid alongside of Galway. Near where they lay was a large pit dug by the explosion of a mortar-shell. It was soon prepared for the reception of the bodies,—a fitting resting-place for two gallant soldiers.

The preparations for the funeral were few and simple. Our enemies had learned of the accident and its fatal consequences, and in the true spirit of chivalry, sent a chaplain to officiate at the funeral. Two companies of South Carolina troops without arms also attended, having come over in a steamboat for the purpose. After the ceremony they withdrew, and left the Sumter garrison alone.

Meantime, the steamer “Planter” had arrived, and the wounded were carried on board. The severely wounded man, who had lain alongside his dead comrades, and, as he afterwards told me, had heard and understood the funeral services, although unable to speak, was considered to be too severely injured to be moved. No one believed that he could recover. No one believed that he was conscious of anything that was going on. But he was; and he said, after he recovered, that when he heard the determination to leave him behind, it nearly broke his heart. The surgeon-general of South Carolina promised to care for him, and if he should recover and wish to go North, to see that he was provided with a pass for that purpose. He did recover, and rejoined his company at Fort Hamilton, New York harbor, some time in May, on a pass signed by General Beauregard. His term of enlistment expired soon afterwards, and, although he desired to re-enlist, his injuries, and the partial loss of sight in one eye, were sufficient to cause his rejection. His name was George Fielding. He was an illiterate Irishman, but his heart was loyal, and as true as steel. He afterwards enlisted in a Michigan regiment and was killed, I think, in one of the battles on the Peninsula.

The time for our departure had come, assembly sounded in Sumter for the last time. The column was formed, the flag of Moultrie and Sumter, wrapped around the topmast which had been shot down, was carried on the shoulders of six sergeants in advance, and the garrison marched out to the inspiring strains of “Yankee Doodle.” The “Planter” carried us to the steamer “Isabel,” which next morning carried us to the fleet.

JAMES CHESTER,

Captain Third Artillery.

- Chester, James. “The First Scenes of the Civil War.” The United Service. A Monthly Review of Military and Naval Affairs. Vol.10, no. 6, June 1884.

- Born in Scotland, James Chester was an artillery sergeant at Fort Sumter when Confederate forces fired on the fort in April 1861 in the opening hostile exchange of the American Civil War.

- Hand-tinted image of Fort Sumter of a black and white engraved print in Frank Leslie’s Scenes and Portraits of the Civil War, 1894. (Special handed-tinted off-prints were sold separately from original publications.)

- (a) irishacw, “The Lives of Her Exiled Children Will be Offered in Thousands”: Edward Gallway, Fort Sumter & Foreseeing the Cost of Civil War. Irish in the American Civil War, March 23, 2020.

- (b) The first soldier to lose his life in the American Civil War was Daniel Hough, a former farmer from Co. Tipperary.

- (c) Edward Gallway, well-educated and worked as a clerk before enlisting on November 23, 1859 in Moultrievile, SC. Description: 5 feet 9 inches tall, with grey eyes, fair hair and a fair complexion. U.S. Army Register of Enlistments states: “died Apr. 14 ’61 accidental explosion of gunpowder while firing salute after bombdt at Ft. Sumter S.C.” From Skibbereen, Cork County, Ireland

- irishacw

- Private Galloway died at the Gibbes Hospital in Charleston. (House Divided)

- Gilles Hospital (WikiTree)