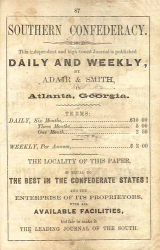

April 9, 1863, Southern Confederacy (Atlanta, Georgia)

The following is applicable in other sections besides New Jersey.

I am a farmer, and so was my father before me. I have not followed in his footsteps in the way of managing the farm, because I have taken agricultural papers and have learned much that was not his to know; and what’s more, the railroad has come within three miles of me, so that the old farm upon which my father toiled many years is worth five times what it was in his day. I am not one of the kind of men who croak and grumble about old times. I enjoy modern times, and would not give up my machines, and go back to the old way of doing things by hand for any money. I often wonder if my father can look down from Heaven, and see the mowers and reapers fly over the old places where he toiled and sweated. I cannot help chuckling to myself, as I sit in my sulky, and ride over the old familiar places, cutting down the grass, and raking it up again, like a half-a-dozen men; to think my boys can go to school all the year round, and never suffer from the want of learning, as I do even to this day.

My wife is up to the times, too, and likes to give her family a good chance in the world. She is a good manager, rising early, and rising to some purpose. I owe half of my prosperity to her help and counsel. My boys are growing up healthy, sensible young fellows. The two oldest harness up the old mare and go to the academy, three miles off, and except a little while during hay and harvest, they do not lose a day all the year round. The only thing that troubles me is my daughters.–Nancy, the oldest, is a fine, handsome, smart girl of nineteen. She went to the district school till she was sixteen, and then she had learned all there was to learn there. So we concluded to send her to Mr. Drake’s Seminary, about fifty miles off. She did get along there amazingly. In two years she had learned a pile, and besides, had painted beautiful pictures enough to cover our walls, (though I must confess, I suspect her teacher gave her a lift at that now and then.) She could sing equal to our parson’s wife, and can start the tunes in meeting when the Squire’s away. She knew the French for everything around the house, and understood botany, chemistry, natural philosophy, and more than I could mention.

While she was at Mrs. Drake’s she only came home at fall and spring vacations, and then was so busy sewing and getting ready to go back again, that her mother did not think it worth while to set her to work. Well last spring she came home for good, and a joyful day it was for me. I felt happy to think I had a daughter who had a good education in her head, and spry and healthy hands to work. But, Mr. Editor, she is a spoiled girl, for aught I can see, but her mother thinks she will come to after a while.

She can’t bear to see me in my shirt sleeves, no matter how clean and white, but insists upon my wearing a linen duster, for she has learned that “it is disgusting to eat with a man in his shirt-sleeves.” She is right down ashamed of her mother’s hands because they show that she has been a hard-working woman all her life.–Our home-made striped carpets that have always been my pride, are “not fit to be seen.”–She won’t let Bob or Dick run about barefooted, for she says they look like beggars.–She has written their names in the spelling books Bobbie and Dickie, and written her’s Nancie Smythe. She says she would rather not eat with servants–that is our hired man and woman, who have lived with us six years, and were born and raised on the next farm. It makes her sick to smell pork and cabbage. She has not forgotten how to milk, but if any body rides by when she is milking, she gets behind the cow and hides her head, as if she was stealing the milk. I have stood these things without saying much until last Sunday; when she insisted upon our hired people sitting up in the gallery, because we needed all our pew room.

I hired two pews, to have room for all. I knew she expected two boarding school misses to make a visit, and was planning to get our men-folks out of sight. I bolted out at this, and had a regular blow-up, and told Nancy she was getting too big feeling entirely for a farmer’s daughter. She staid at home from church and cried all day. I hate crying women more than a long drought, so I shan’t scold her again. I don’t want to be hard on the girl, but what am I to do? I am willing to let her feed the chickens in gloves, and spell all our names wrong, and I’d just as lief have the boys wear shoes; but when it comes to overturning everything, and being ashamed of her father, mother, and home, I am discouraged. I have bought her a piano, and let her learn music for two years, for she is naturally musical. She came near fainting one night when the Squire’s son, just out of college, and a whiskered chap from the city was here, because I said: “Come, Nance, give us a tune on the piany.” I saw something was wrong, but could not guess what, for I had on my duster, and wasn’t tippling my chair back, (a “vulgar trick,” Nancy calls it.) The next day my wife told me what was to pay. I must say I like my old fashioned way of pronouncing as well as her new fashioned way of spelling. And only this morning, after breakfast, when her ma told her to shake the table-cloth, what does she do, but take it away through the long hall and out the back door, for fear some one would see her shake it in the same place where she had for ten years. I’ve got a new boughten carpet for the parlor, and now she wants the front windows cut down to the floor.

Yesterday she came to me to know if she might “teach district school?” “No,” said I, “why do you want to teach? I am able to keep six girls like you, if I had them. No, I can’t think of you teaching.” Upon this she began to cry again, and I can’t stand woman’s tears, so I said, “teach,” and she is going to teach all Winter and Summer, in a little bit of a school house, not as good as my pig house, for fear she will get tanned and freckled, and spoil her hands helping her mother.

Now, Mr. Editor, I have given up Nancy, but I have three fine girls growing up. I am able and willing to give them all a good education, for I believe in it, in spite of the dreadful blunder I have made. I would like to know if you can tell us of any place where a farmer’s daughter can get a good education and not lose her senses. I can’t stand it; to have our other girls get too big for our old fashioned farm house; I want them sensible, well-informed women, but I set down my foot against having them all turn school teachers,.–John Smith in Newark Advertiser.