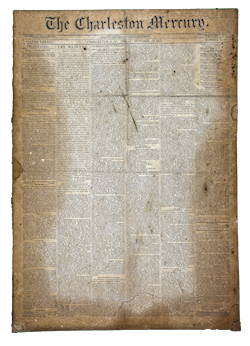

June 12, 1863, The Charleston Mercury

Day by day the track of the destroyer becomes broader. Two-thirds of Virginia, two-thirds of Tennessee, the coasts of North and South Carolina, part of Georgia, nearly all of Florida, Northern Mississippi, Western and Southern Louisiana, a great part of Arkansas and Missouri, have already been laid waste, and every hour brings tidings of fresh destruction. Telegrams of Saturday informed us that the enemy had destroyed a million of dollars worth of property on the Combahee and stolen a thousand negros; it was but a few days ago that they ravaged the county of Mathews in this State, and even while we write tidings come to us that they are burning private houses and destroying every grain of corn they can lay hands on in the county of King and Queen.

Enough has been said of the barbarism of this mode of warfare, and too much has to be confessed of the entire impunity with which it is carried on. Our outcries and our admissions of the weakness or the imbecility of our forces in the field but add to the hellish joy of the foe, without stimulating troops, Government or people to the pitch of retributive vengeance. The belt of desolation widens hourly, nor is there much prospect of an abatement of the evil. Citizens complain of the Government, which in turn complains of the citizens. Meantime common inquiry is made as to the existence and present whereabouts of the organized forces of the Confederacy.

We may be sure this state of things will continue so long as the war is waged exclusively on Confederate soil. Every day the enemy remains in our territory will add to the width of the belt of desolation, and they who now fancy themselves out of danger will soon discover their mistake. If a thousand Yankee cavalry can ride entirely through the State of Mississippi, without molestation, what is to hinder a like number from going through Virginia, North and South Carolina to Port Royal? Certainly unarmed and unorganized citizens will not hinder them.

The belt of desolation serves many purposes of the Yankee nation. It opens a way to free labor and Northern settlers; it diminishes production and concentrates Southern population within limits inadequate to their support, it prepares a place for Yankee emigration if peace on the basis of separation is declared. But this is not all. It answers the purposes of war as well as peace, by interposing a country destitute of supplies between our own and the Yankee border. Thus it is a safeguard against invasion. If Lee should advance, he must move through a desert, dragging immense trains of food behind him. The case is the same with Bragg, with Johnston, with Price. Indeed we hear that Price will on this account find it difficult, if not impossible, to enter Missouri. In front of all our large armies lies a waste, where there is food for neither man nor beast. Girded by a belt of desolation, the North is safe from invasion; the broader the belt the greater its security. As the months wane and the years roll on, the South, unless something be done, will become, in the language of Scripture, […..] abomination of desolation.’ We believe that something will be done – the necessity of the case demands it imperatively; would that we could be sure that it will be done speedily. This cup can be returned to the lips of the North drugged with ten fold bitterness. Mercy to ourselves demands this act of retributive justice to them.

RICHMOND WHIG.