For the purpose of this listing, “author” refers to the diarists, journal writers, compilers or other types of creators of “works.”

“As a general rule, the author is the party who actually creates the work, that is, the person who translates an idea into a fixed, tangible expression entitled to copyright protection.” – Thurgood Marshall.

For now, this a work very much in progress.

Th e Battle Brothers—Letters from two brothers who served in the 4th North Carolina Infantry during the Civil War are available in a number of sources online. Unfortunately, the brothers are misidentified in some places as Walter Lee and George Lee when their names were actually Walter Battle and George Battle.

e Battle Brothers—Letters from two brothers who served in the 4th North Carolina Infantry during the Civil War are available in a number of sources online. Unfortunately, the brothers are misidentified in some places as Walter Lee and George Lee when their names were actually Walter Battle and George Battle.

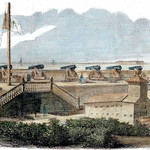

Jame s Chester—A career artillery soldier who climbed the ranks from private to major, John had at least 3 articles published relating his time at Forts Moultrie and Sumter in Charleston Harbor.

s Chester—A career artillery soldier who climbed the ranks from private to major, John had at least 3 articles published relating his time at Forts Moultrie and Sumter in Charleston Harbor.

Margaret Ann “Meta” Morris Grimball was born in 1810. A descendent of Lewis Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, in 1 830, she married John Berkley Grimball (1800-1892), who owned a rice plantation near Adam’s Run, South Carolina—west of Charleston—, raising nine children on the plantation and in Charleston. During the Civil War, the family sought safety in Spartanburg, South Carolina. The plantation, confiscated by federal troops, was returned to the family in 1866. Unable to make mortgage payments they lost the house in 1870. Meta died in 1881. In Meta’s journal, she records the major events of the day and their effect on her family’s life, juxtaposing common domestic concerns with larger issues related to the Civil War, including slavery, personal safety, and religion. The journal closes with an entry describing some of the family’s hopeful plans for survival.

830, she married John Berkley Grimball (1800-1892), who owned a rice plantation near Adam’s Run, South Carolina—west of Charleston—, raising nine children on the plantation and in Charleston. During the Civil War, the family sought safety in Spartanburg, South Carolina. The plantation, confiscated by federal troops, was returned to the family in 1866. Unable to make mortgage payments they lost the house in 1870. Meta died in 1881. In Meta’s journal, she records the major events of the day and their effect on her family’s life, juxtaposing common domestic concerns with larger issues related to the Civil War, including slavery, personal safety, and religion. The journal closes with an entry describing some of the family’s hopeful plans for survival.

John Beauchamp Jones—A popular novelist (particularly of the American  West and the American South) and a well-connected literary editor and political journalist in the two decades leading up to the American Civil War, Jones served in the Confederate War Department and is today, above all, remembered for his published diary, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital.

West and the American South) and a well-connected literary editor and political journalist in the two decades leading up to the American Civil War, Jones served in the Confederate War Department and is today, above all, remembered for his published diary, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital.

Charles H. Lynch—Enlisting in the 18th Connecticut Volunteers on August 6th, 1862, Charles served through July 7th, 1864, when the regiment was disbanded. The regiment served in western Maryland and the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. He records mundane things like “wash day” as well as swimming and bathing when he has the chance. The diary includes the New Market, Lynchburg, and Monocacy campaigns.

Charles H. Lynch—Enlisting in the 18th Connecticut Volunteers on August 6th, 1862, Charles served through July 7th, 1864, when the regiment was disbanded. The regiment served in western Maryland and the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. He records mundane things like “wash day” as well as swimming and bathing when he has the chance. The diary includes the New Market, Lynchburg, and Monocacy campaigns.

Robert M. Magill—Son of Robert McGill and Fannie  Lowrie, Robert was born and raised in northern Georgia less than 20 miles from the battlegrounds of Chicamauga. Growing up in a family opposed to owning slaves, in the spring of 1862, he and his brother Thomas faced the Confederate Conscript Act that had been passed April 26, 1862, which made any white male between 18 to 35 years old liable to three years of military service. which forced every man between the ages of eighteen and forty-five, Their dilemma, as Robert saw it, was to (1) volunteer, (2) “be conscripted and placed in a company not of your own choosing and bear the odious name of conscript,” or (3) try to go North, “turning our backs on the home of our childhood and a widowed mother, and run a risk of ten to one of being captured and shot as a traitor to the Southern cause.” They chose to volunteer and joined the same company another brother was in. (Note: image is of an unidentified Confederate soldier.)

Lowrie, Robert was born and raised in northern Georgia less than 20 miles from the battlegrounds of Chicamauga. Growing up in a family opposed to owning slaves, in the spring of 1862, he and his brother Thomas faced the Confederate Conscript Act that had been passed April 26, 1862, which made any white male between 18 to 35 years old liable to three years of military service. which forced every man between the ages of eighteen and forty-five, Their dilemma, as Robert saw it, was to (1) volunteer, (2) “be conscripted and placed in a company not of your own choosing and bear the odious name of conscript,” or (3) try to go North, “turning our backs on the home of our childhood and a widowed mother, and run a risk of ten to one of being captured and shot as a traitor to the Southern cause.” They chose to volunteer and joined the same company another brother was in. (Note: image is of an unidentified Confederate soldier.)

Dora Richards Miller—Born in St. Thomas in the Danish Virgin Islands and raised in the Frederiksted, St. Crois home of a grandmother who had freed all her late husband’s slaves, Dora Richards started her diary as a single, pro-Union, 25-year-old woman in New Orleans, Louisiana. Within months, she was married to Anderson Miller, an Arkansas lawyer and living in a small Arkansas delta county seat. With the Mississippi flooding, “swamp fever” raging, and food supplies disrupted by the needs of a rebel army, their Arkansas home wasn’t a refuge for long. Trying to find a safer place where Anderson can ply his trade, they ended up in Vicksburg just before the beginning of the Vicksburg campaign and got stuck there until after the city fell. Years later, a widow with two sons, to protect her job as a teacher in New Orleans, her diary was published anonymously in two magazine articles and two books as “A Woman’s Diary of the Siege of Vicksburg” and “War Diary of a Union Woman in the South,” all edited by George W. Cable. (Besides teaching Dora Miller was also an author and inventor. Her story about her life in St. Croix and her observations and experiences during the July 1848 slave revolt was published in 1892 as “A West Indian Slave Insurrection” in Scribner’s.)

Dora Richards Miller—Born in St. Thomas in the Danish Virgin Islands and raised in the Frederiksted, St. Crois home of a grandmother who had freed all her late husband’s slaves, Dora Richards started her diary as a single, pro-Union, 25-year-old woman in New Orleans, Louisiana. Within months, she was married to Anderson Miller, an Arkansas lawyer and living in a small Arkansas delta county seat. With the Mississippi flooding, “swamp fever” raging, and food supplies disrupted by the needs of a rebel army, their Arkansas home wasn’t a refuge for long. Trying to find a safer place where Anderson can ply his trade, they ended up in Vicksburg just before the beginning of the Vicksburg campaign and got stuck there until after the city fell. Years later, a widow with two sons, to protect her job as a teacher in New Orleans, her diary was published anonymously in two magazine articles and two books as “A Woman’s Diary of the Siege of Vicksburg” and “War Diary of a Union Woman in the South,” all edited by George W. Cable. (Besides teaching Dora Miller was also an author and inventor. Her story about her life in St. Croix and her observations and experiences during the July 1848 slave revolt was published in 1892 as “A West Indian Slave Insurrection” in Scribner’s.)

Horatio Nelson Taft—Author of a diary set in civil war Washington, D.C.,  Horatio Nelson Taft’s family had remarkable unofficial connections and access to the first family of the United States during the early months of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency and, later, at the very end. His youngest children were playmates of Lincoln’s sons and his oldest son, a physician, was in the audience at Ford’s theater when the president was shot and attended Lincoln shortly afterward through to his death. Recording much of his experiences and observations in Washington during the war years, Taft’s three-volume diary remained with the family until presented to the Library of Congress in 2002. The diary’s account of the assassination of Lincoln may include the only new information on that terrible event that has surfaced in the last 60 or 70 years.

Horatio Nelson Taft’s family had remarkable unofficial connections and access to the first family of the United States during the early months of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency and, later, at the very end. His youngest children were playmates of Lincoln’s sons and his oldest son, a physician, was in the audience at Ford’s theater when the president was shot and attended Lincoln shortly afterward through to his death. Recording much of his experiences and observations in Washington during the war years, Taft’s three-volume diary remained with the family until presented to the Library of Congress in 2002. The diary’s account of the assassination of Lincoln may include the only new information on that terrible event that has surfaced in the last 60 or 70 years.

Louise Wigfall Wright —daughter of Louis T and Charlotte Wigfall. Fourteen years old at the time of the firing on Fort Sumpter and living with maternal Grandparents near Boston, she shares letters, telegrams, articles and dispatches from the early days of the war and before.

—daughter of Louis T and Charlotte Wigfall. Fourteen years old at the time of the firing on Fort Sumpter and living with maternal Grandparents near Boston, she shares letters, telegrams, articles and dispatches from the early days of the war and before.