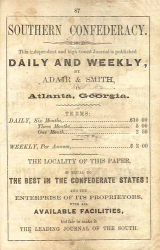

Southern Confederacy [Atlanta, Ga],

September 28, 1862

Written expressly for the Southern Confederacy.

These organizations are springing up thickly around us; nearly every county in the State has one, and some have half a dozen. So far so good — we cannot do too much for our soldiers. But just where there are so many societies, there is, strange to say, great danger that the least good will be done. This arises from the fact that while they are in the same county, formed for the same purpose, and working, perhaps, for the very same companies, there is a lack of disposition on the part of the members to have any correspondence with each other, or to establish a communication in common with some central Society, through which unanimity of action, and equality of distributions to each Company might be secured.

A letter has just been handed to me, written by a friend in a distant part of the country, who is resident in a large town where one of these Societies has been organized; and she tells me that though it is at the county site, and is a most advantageous point for transportation, it is difficult to obtain any cooperation from the smaller district associations. There appears to exist among them a species of jealousy–a fear lest they should not get due credit for their contributions in money and clothing, were they forwarded through other hands than their own. More counties than one are afflicted with false notions on this head, and a serious affliction it will prove to be, unless they can be done away with. Is there not a different, a more correct view?

Suppose an association has been formed in a central village, for the whole county: It does not supersede the necessity for District Societies, nor do its members arrogate to themselves any superiority over such societies–Neither would they take one iota of the praise which their efforts deserve. All they ask is for full information as to their proceedings.

“Let us know,” they say, “what you are doing and for whom. Some of you are in portions of the country far from the railroad and find it inconvenient to transmit your packages. If you will send them to us, with the names of the donors attached thereto, and the names and location of the soldiers for whom they are designed, we will carefully pack them for you and forward them exactly according to your order. We do not want the name of doing your work, but we want to prevent confusion that must arise if we work in a scattered, unsystematic way. We will take special pains to have it known that the donation is yours, not ours.”

Correspondence and cooperation in some such manner is absolutely necessary. Several companies go from one county. Each society works more or less for these, as choice and fancy dictate. The consequence is, that in one company there is a deficiency of clothing that the society of which it is the favorite cannot supply; in another a superfluity of garments has been provided by a wealthier association, while yet another is but poorly accoutered, even by the utmost efforts of some little band devoted to its service. Now, if this were reported at the headquarters of a central association, and the distribution of clothing regulated accordingly, the extra quantity might be so divided, and the individual efforts of the association so applied as to furnish every company with what is needful, without waste of money or effort. And we should remember that if this war continues long, every cent uselessly expended may prove a bitter loss–every misdirected effort will be a cruel mockery of the wants of some perishing soldier.

My friend’s letter has furnished me a text for the times. Is it possible that now, when everything depends upon united, energetic action, some people are standing aloof from one another, in fear that, if they band together, some little scraps of credit may be detached from their good deeds as individuals! And, after all, some of them have only half fulfilled their real duty. For shame!

Our volunteers appeal to us for aid–“Yes, yes, you shall have it, all we can give; but we will have no connection with this society, and that shall not know what we are doing, and we cannot promise you much.” So, the winter closes in, and these rambling donations are sent off. An ill-assorted variety, they are worse divided–some soldiers are amply supplied, others are almost destitute.

As one by one they yield to the effects of the piercing blasts, and the soil of Virginia is dotted with the graves of those slain, not by the sword, not by pestilence, but by exposure alone, whose will the fault be?

Had this principle, established by some of our aid societies, prevailed in our political administration, we should have to-day no combined forces to oppose our foes, and no united leaders to command them, were they banded. David would stand aloof from Stephens and the Cabinet; Beauregard and the rest of the Generals would be wrangling for the “credit” of the victory of Manassas Plains, and ere the last Autumn sunset could cast its shadows over our landscape, Lincoln would be triumphant, and the “Southern Confederacy” live only in dreams.

Cooperation is indispensable to harmony of action; harmony is the soul of collective energy and efficiency.

Unanimity and success, discord and failure, or, at best, but partial achievements. There is our choice.

ZIOLA.