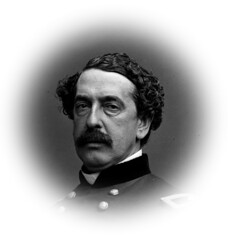

by Abner Doubleday

CHAPTER III.

PRELIMINARY MOVEMENTS OF THE SECESSIONISTS.

Arrival of Major Anderson.—Huger’s Opposition to a Premature Assault on Fort Moultrie.—Anderson’s Report to the Secretary of War.—Active Preparations by the South Carolinians.—Meeting of Congress.—Attempts at Compromise.—Secession Batteries at Mount Pleasant.—Arrival of Major Buell with written Orders.—Vain Efforts to Strengthen Castle Pinckney.—Northern Opinion.—Public Meeting in Philadelphia.

It was now openly proclaimed in Charleston that declarations in favor of the Union would no longer be tolerated; that the time for deliberation had passed, and the time for action had come.

On the 21st our new commander arrived and assumed command. He felt as if he had a hereditary right to be there, for his father had distinguished himself in the Revolutionary War in defense of old Fort Moultrie against the British, and had been confined a long time as a prisoner in Charleston. We had long known Anderson as a gentleman; courteous, honest, intelligent, and thoroughly versed in his profession. He had been twice brevetted for gallantry—once for services against the Seminole Indians in Florida, and once for the battle of Molino del Roy in Mexico, where he was badly wounded. In politics he was a strong pro-slavery man. Nevertheless, he was opposed to secession and Southern extremists. He soon found himself in troubled waters, for the approaching battle of Fort Moultrie was talked of everywhere throughout the State, and the mob in Charleston could hardly be restrained from making an immediate assault. They were kept back once through the exertions of Colonel Benjamin Huger, of the Ordnance Department of the United States Army. As he belonged to one of the most distinguished families in Charleston, he had great influence there. It was said at the time that he threatened if we were attacked, or rather mobbed, in this way, he would join us, and fight by the side of his friend Anderson.1 Colonel Memminger, afterward the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury, also exerted himself to prevent any irregular and unauthorized violence.

An additional force of workmen having arrived from Baltimore, Captain Foster retained one hundred and twenty to continue the work on Fort Moultrie, leaving his assistant, Lieutenant Snyder, one hundred and nine men to finish Fort Sumter.

On the 1st of December, Major Anderson made a full report to Secretary Floyd in relation to our condition and resources. It was accompanied with requisitions, in due form, for supplies and military material. Colonel Gardner, before he left, had already applied for rations for the entire command for six months.

Previous to Lincoln’s election, Governor Gist had stated that in that event the State would undoubtedly secede, and demand the forts, and that any hesitation or delay in giving them up would lead to an immediate assault. Active preparations were now in progress to carry out this threat. In the first week of December we learned that cannon had been secretly sent to the northern extremity of the island, to guard the channel and oppose the passage of any vessels bringing us re-enforcements by that entrance. We learned, too, that lines of countervallation had been quietly marked out at night, with a view to attack the fort by regular approaches in case the first assault failed. Also, that two thousand of the best riflemen in the State were engaged to occupy an adjacent sand-hill and the roofs of the adjoining houses, all of which overlooked the parapet, the intention being to shoot us down the moment we attempted to man our guns. Yet the Administration made no arrangements to withdraw us, and no effort to re-enforce us, because to do the former would excite great indignation in the North, and the latter might be treated as coercion by the South. So we were left to our own scanty resources, with every probability that the affair would end in a massacre. Under these circumstances the appropriating of $150,000 to repair Fort Moultrie and $80,000 to finish Fort Sumter by the mere order of the Secretary of War, without the authority of Congress, was simply an expenditure of public money for the benefit of the Secessionists, and I have no doubt it was so intended. Forts constructed in an enemy’s country, and left unguarded, are built for the enemy.

Congress met on the 3d of December, but took no action in relation to our peculiar position. As usual, their whole idea was to settle the matter by some new compromise. The old experiment was to be tried over again: St. Michael and the Dragon were to lie down in peace, and become boon companions once more.

The office-holders in the South, who saw in Lincoln’s election an end to their pay and emoluments, were Secessionists to a man, and did their best to keep up the excitement. They tried to make the poor whites believe that through the reopening of the African slave-trade negroes would be for sale, in a short time, at thirty dollars a head; and that every laboring man would soon become a rich slave-owner and cotton-planter. To the timid, they said there would be no coercion. To the ambitious, they spoke of military glory, and the formation of a vast slave empire, to include Mexico, Central America, and the West Indies. The merchants were assured that Charleston would be a free port, rivaling New York in its trade and opulence.

They painted the future in glowing colors, but the present looked dreary enough. All business was at an end. The expenses of the State had become enormous, and financial ruin was rapidly approaching. The heavy property-owners began to fear they might have to bear the brunt of all these military preparations in the way of forced loans.2 For a time a strong reaction set in against the Rhett faction, but intimidation and threats prevented any open retrograde movement.

Among those who were reported to be most clamorous to have an immediate attack made upon us, was a certain captain of the United States Dragoons, named Lucius B. Northrup; afterward made Paymaster-general of South Carolina, and subsequently, through the personal friendship of Jeff. Davis, promoted to be Commissary-general of the rebel army. He had resided for several years in Charleston on sick-leave, on full pay. Before urging an assault he should have had the grace to resign his commission, for his oath of office bound him to be a friend to his comrades in the army, and not an enemy. I am tempted, in this connection, to show how differently the rebel general Magruder acted, under similar circumstances, when he was a captain and brevet colonel in our service. He said to his officers, the evening before he rode over the Long Bridge, at Washington, to join the Confederates, “If the rebels come tonight, we’ll give them hell; but tomorrow I shall send in my resignation, and become a rebel myself.”

Amidst all this turmoil, our little band of regulars kept their spirits up, and determined to fight it out to the last against any force that might be brought against them. The brick-layers, however, at work in Fort Sumter were considerably frightened. They held a meeting, and resolved to defend themselves, if attacked by the Charleston roughs, but not to resist any organized force.

On the 11th of December we had the good fortune to get our provisions from town without exciting observation. They had been lying there several days. It was afterward stated in the papers that the captain of the schooner was threatened severely for having brought them. On the same day the enemy began to build batteries at Mount Pleasant, and at the upper end of Sullivan’s Island, guns having already been sent there. We also heard that ladders had been provided for parties to escalade our walls. Indeed, the proposed attack was no longer a secret. Gentlemen from the city said to us, “We appreciate your position. It is a point of honor with you to hold the fort, but a political necessity obliges us to take it.”

My wife, becoming indignant at these preparations, and the utter apathy of the Government in regard to our affairs, wrote a stirring letter to my brother, in New York, stating some of the facts I have mentioned. By some means it found its way into the columns of the Evening Post, and did much to call attention to the subject, and awaken the Northern people to a true sense of the situation. She was quite distressed to find her hasty expressions in print, and freely commented on both by friends and enemies. I may say, in passing, that the distinguished editor of that paper, William Cullen Bryant, proved to be one of the best friends we had at the North. George W. Curtis, who aided us freely with his pen and influence, was another. They exerted themselves to benefit us in every way, and were among the first to invoke the patriotism of the nation to extricate us from our difficulties, and save the union of the States. When we returned to New York, they and their friends gave us a cordial and heartfelt welcome.

To resume the thread of my narrative. The fort by this time had been considerably strengthened. The crevices were filled up, and the walls were made sixteen feet high, by digging down to the foundations and throwing up the surplus earth as a glacis. Each of the officers had a certain portion given him to defend. I caused a sloping picket fence, technically called a fraise, to be projected over the parapet on my side of the work, as an obstacle against an escalading party. I understood that this puzzled the military men and newspapers in Charleston exceedingly. They could not imagine what object I could have in view. One of the editors said, in reference to it, “Make ready your sharpened stakes, but you will not intimidate freemen.”

There was one good reason why our opponents did not desire to commence immediate hostilities. The delay was manifestly to their advantage, for the engineers were putting Fort Sumter in good condition at the expense of the United States. They (the rebels) intended to occupy it as soon as the work approached completion. In the mean time, to prevent our anticipating them, they kept two steamers on guard, to patrol the harbor, and keep us from crossing. These boats contained one hundred and twenty soldiers, and were under the command of Ex-lieutenant James Hamilton, who had recently resigned from the United States Navy.

The threatening movements against Fort Moultrie required incessant vigilance on our part, and we were frequently worn out with watching and fatigue. On one of these occasions Mrs. Seymour and Mrs. Doubleday volunteered to take the places of Captain Seymour and myself, and they took turns in walking the parapet, two hours at a time, in readiness to notify the guard in case the minute-men became more than usually demonstrative.

In December the secretary sent another officer of the Inspector-general’s Department, Major Don Carlos Buell, to examine and report upon our condition. Buell bore written orders, which were presented on the 11th, directing Major Anderson not to provoke hostilities, but in case of immediate danger to defend himself to the last extremity, and take any steps that he might think necessary for that purpose. There would appear to be some mystery connected with this subject, for Anderson afterward stated to Seymour, as a reason for not firing when the rebels attempted to sink the Star of the West, that his instructions tied his hands, and obliged him to remain quiescent. Now, as there are no orders of this character on record in the War Department, they must have been of a verbal and confidential nature. In my opinion, Floyd was fully capable of supplementing written orders to resist, by verbal orders to surrender without resistance. If he did so, I can conceive of nothing more treacherous, for his object must have been to make Anderson the scape-goat of whatever might occur. Buell, however, is not the man to be the bearer of any treacherous communication. Still, he did not appear to sympathize much with us, for he expressed his disapproval of our defensive preparations; referring particularly to some loop-holes near the guard-house, which he said would have a tendency to irritate the people. I thought the remark a strange one, under the circumstances, as “the people” were preparing to attack us. I had no doubt, at the time, in spite of the warlike message he had brought, that Buell’s expressions reflected the wishes of his superiors. I have ascertained recently that Floyd did have one or more confidential agents in Charleston, who were secretly intermeddling in this matter, without the sanction of the President or the open authority of the War Office. It appears from the records that another assistant adjutant-general, Captain Withers, who joined the rebels at the outbreak of the rebellion, and became a rebel general, was also sent by Floyd to confer with Anderson. It is not at all improbable, therefore, that some one of the messengers who actually joined the enemy may have been the bearer of a treasonable communication. It appears from Anderson’s own statement that his hands were tied, and no one that knew him would ever doubt his veracity. Yet, if he really desired to retain possession of Charleston harbor for the Government, and Floyd’s orders stood in his way, why did he not, after the latter fled to the South, make a plain statement to the new secretary, Judge Holt, whose patriotism was undoubted, and ask for fresh instructions? It looks to me very much as if he accepted the orders without question because he preferred the policy of non-resistance.

I shall have occasion to refer to this subject again in the course of my narrative.

We had frequently regretted the absence of a garrison in Castle Pinckney, as that post, being within a mile of Charleston, could easily control the city by means of its mortars and heavy guns. We were too short-handed ourselves to spare a single soldier. The brave ordnance-sergeant, Skillen, who was in charge there, begged hard that we would send him a few artillerists. He could not bear the thought of surrendering the work to the enemies of the Government without a struggle, and would have made a determined resistance if he could have found any one to stand by him. We talked the matter over, and Captain Foster thought he could re-enforce Skillen by selecting a few reliable men from his masons to assist in defending the place. He accordingly sent a body of picked workmen there, under his assistant, Lieutenant R. K. Meade, with orders to make certain repairs. The moment, however, Meade attempted to teach these men the drill at the heavy guns, they drew back in great alarm, and it was soon seen that no dependence could be placed upon them. So Castle Pinckney was left to its fate.

As the General Government seemed quietly to have deserted us, we watched the public sentiment at the North with much interest. There was but little to encourage us there. The Northern cities, however, were beginning to appreciate the gravity of the crisis. At the call of the Mayor of Philadelphia, a great public meeting was held in Independence Square. For one, I was thoroughly dispirited and disgusted at the resolutions that were passed. They were evidently prompted by the almighty dollar, and the fear of losing the Southern trade. They urged that the North should be more than ever subservient to the South, more active in catching fugitive slaves, and more careful not to speak against the institution of slavery. As a pendant to these resolutions, an official attempt was made, a few days afterward, to prevent the eloquent Republican orator, George W. Curtis, from advocating the Northern side of the question.

- He left the United States service soon after the attack on Fort Sumter, and joined the Confederates. He did so reluctantly, for he had gained great renown in our army for his gallantry in Mexico, and he know he would soon have been promoted to the position of Chief of our Ordnance Department had he remained with us.

- About a month afterward the Honorable William Aiken, who was a Union man, and who had formerly been governor of the State, and a member of Congress, was compelled to pay forty thousand dollars as his share of the war taxes