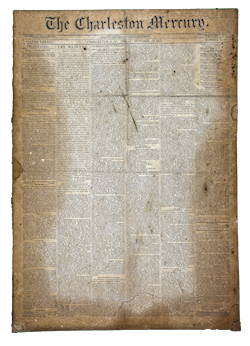

April 2, 1861; The Charleston Mercury

WASHINGTON, March 28, 1861. It is fair to assume that Mr. LINCOLN has no inclination to be separated from his party. His first act as President was to reiterate his adherence to the Chicago platform, and from then till now he has in everything paid homage to the Black Republican idols. In the absence of explicit avowals on his part, then, he may–and, indeed, must–be judged in the light reflected by his friends and adherents in the Senate; for though he has been silent, Republican Senators have spoken; though he has studiously concealed his policy, Senators have done much toward an exposition of its nature. Negatively, at any rate, the closing days of the Senate have taught an instructive lesson. We are at least permitted to know what shall not be done. We have been enabled to take measure of the sincerity of the peace professions current in certain Republican quarters, and to estimate the worth of the overtures with which the Submissionists in the Border States would fain be satisfied. How and with what result? Three notable points compose the answer: First, the Republican Senators, being a majority, have refused to affirm the adoption of any change in the purposes of their party. They have refused to declare the slightest modification of their views and plans in relation to the exclusion of slavery from the Territories, virtually admitting, therefore, that the non-insertion of WILMOT Proviso in the territorial acts of the recent session, resulted from confidence in the power of the Executive to adapt the territorial institutions to the abolition standard, and not from any disposition to meet the issue presented by the Southern movement. Second, they have stubbornly resisted every attempt to elicit an authoritative explanation of the course marked out by Mr. LINCOLN in reference to the Southern Confederacy. Third, without having manliness enough to avow their partiality for coercive measures, they have crushed successive efforts to throw the weight of the Senate’s counsel into the scale of peace. To some extent, perhaps, the Republican Senators are entitled to credit. They have at least abstained from hypocrisy. They have not mocked the South with conciliatory pretences, nor insulted it by gratuitous lying. If they declined to proclaim themselves enemies, it was not, because they were eager to affect the air of friends. HALE and FESSENDEN, and TRUMHULL and SUMNER, were granted free scope, and were glorified. There was no rebuke for Abolition ;’no patting on the back for oily .’The DOUGLASES and JOHNSONS of the body were allowed to be the monopolists of gammon. Democratic Union savers did the shrieking, and the Republicans rewarded them with laughter. Mr. LINCOLN is not acting with equal ingenuousness. He is trying to bestraddle two unharmonious hobbies. Take him at his word, and he is at once for concession and coercion. If it were not treason to speak evil of dignitaries in this latitude, he might be called a thimble rigger–so fond is he of displaying dexterity in the art of political trickery. Now, with a wink, he professes to be the most conciliatory of Presidents; anon, with eyes wide open, he is for the enforcement of the laws all over the Union, as it stood prior to his election. He for coercion, forsooth? Why, is he not withdrawing the troops from Sumter? He for the recognition of rebels? Why, has he not General SCOTT working himself to death, devising schemes for whipping the seceded States back into the Union? Is it that Mr. LINCOLN construes Presidential amiability to mean, being all things to all men? Or that his lack of faith in Northern honesty leads him to take MACHIAVELLI as his Mentor in matters political? But with the record of the Republicans in the Senate fresh before us, Mr. LINCOLN may spare himself much trouble. Everybody sees precisely where he stands. If he leans toward peace, it is because he is not prepared for war. If he abstains from coercive measures, it is because he has learned that coercion is impossible, with the means at his command. If he hesitates to strike a blow at the South, it is because he knows that the rebound would make him a fugitive from Washington, and summarily change the tenancy of the White House. He did not don the Scotch cap at Harrisburg without acquiring a liking for Scottish caution. All his byplay, however, may now be ended. His reticence will profit him not. His friends in the Senate have committed him to a position utterly irreconcilable with frankness and a conciliatory spirit. The only possible condition of peace is an immediate acknowledgment of the fact that the Confederate States have achieved their independence. The Government at Washington must deal with the Government at Montgomery on equal terms–as a friendly though independent power; or the two cannot live as neighbors without a struggle. Upon this point, we are told Mr. LINCOLN’S policy is delay. He endeavors to postpone to a more convenient season the determination which must be arrived at with regard to the Southern Commissioners now here awaiting his reply. Who does not detect the dishonesty of the manoeuvre? At this moment, next to the distribution of the spoils, and the acquisition of income, what is the chief object of the LINCOLN Administration? Notoriously, to prevent the recognition of the Confederate States by the leading powers of Europe. The prompt action of the Montgomery Government, in despatching Commissioners abroad, has startled the Black Republican Cabinet; and vigorous efforts are to be made to defeat the mission of Mr. DUDLEY MANN and his colleagues. The resolve does not admit of misinterpretation. Mr. LINCOLN will not recognize the Southern Confederacy, and no CHARLES FRANCIS ADAMS goes to England, charged with the task of persuading the PALMERSTON Ministry to pursue a similar course. Beat about the question as you may, to this point must you come at last. In the end, after playing with the Southern Commissioners a little longer, Mr. LINCOLN will promulgate the decision, of which, ere then, the British and French Governments will have been advised. He will refuse in any manner to recognize the Confederacy. That Messrs. ADAMS and DAYTON will succeed on the other side of the Atlantic, few suppose. The altered tone of the Republican press upon this subject, shows that that delusion no longer prevails. But, so long as Mr. LINCOLN’S purpose remains unchanged, the consequences, as between the two Confederacies, will be the same.

S.