U. S. TROOP-SHIP ATLANTIC,

Havana, April 25, 1861.

Brig. Gen. J. G. TOTTEN,

Chief of Engineers, Washington:

GENERAL: In obedience to orders from the President of the United States, I accompanied as engineer the expedition of Colonel Brown, fitted out in New York, and sailing under secret and confidential orders to attempt to re-enforce Fort Pickens.

I left Washington on the afternoon of the 3d April, having been engaged from the 31st March in preparation for the expedition.

The Secretary of State having assured me that any arrangement I might make for the preservation and control of the public works under my charge in Washington during my absence would be approved by the Executive, I appointed Capt. J. N. Macomb, Topographical Engineers and my brother-in-law, my attorney to sign checks, draw requisitions, and do all other acts necessary for the control of these public works until my return.

Arrived in New York, I devoted myself, in concert with the commander of the expedition, Col. Harvey Brown, Colonel Keyes, military secretary, and others, to the fitting out of the vessels necessary to convey the troops, horses, artillery, ordnance, and stores to Santa Rosa.

By the request of the President I sailed in the first transport ready, the Atlantic steamer, formerly of the Collins line, with instructions to remain with Colonel Brown until he was established in Fort Pickens, and then to return to my duties in Washington.

We had on board five companies of artillery and infantry, two of which were light artillery, Barry’s and Hunt’s. Captain Barry’s company carried their horses with them, 73 in number. Captain Hunt’s company, having lost their horses by the treachery of General Twiggs in Texas, were dismounted.

Such artillery as could be hastily collected, such part of the stores and supplies for six months for 1,000 men, purchased in New York, as could be embarked by the evening of the 6th April, were placed on board and the vessel hauled into the stream after sunset on that date.

She continued taking in stores during the night and sailed on the morning of the 7th instant. While of many articles large supplies were put on board, not less than fifty days’ rations of any single article of subsistence accompanied us, and we carried with us thirty days’ forage for the horses.

The dock was left covered with stores, shovels, sand bags, forage, subsistence, ammunition, and artillery, to follow with steamer Illinois, to sail on the evening of the 8th.

These two vessels it was believed would carry supplies for 1,000 men for six months.

The uncertainty of the Government as to the condition of Fort Pickens, and as to the very orders and instructions under which the squadron off that fortress was acting, led to apprehensions lest the place might be taken before relief could reach it.

A landing in boats from the mainland on a stormy night was perfectly practicable in spite of the utmost efforts of a fleet anchored outside and off the bar to prevent it. Such a landing in force taking possession of the low flank embrasures by men armed with revolvers would be likely to sweep in a few minutes over the ramparts of Fort Pickens, defended by only forty soldiers and forty ordinary men from the navy-yard, a force which did not allow one man to be kept at each flanking gun.

Believing that a ship of war could be got ready for sea and reach Pensacola before any expedition in force, I advised the sending of such a ship under a young and energetic commander, with orders to enter the harbor without stopping, and, once in, to prevent any boat expedition from the main to Santa Rosa.

Capt. David D. Porter readily undertook this dangerous duty, and, proceeding to New York, succeeded in fitting out the Powhatan, and sailed on the 6th for his destination.

Unfortunately, or rather fortunately, as the result will show, the Powhatan had been put out of commission at Brooklyn and stripped of her crew and stores on the 1st April, only two and a half hours before the telegram from the President, ordering her instant preparation for sea reached the commander of the navy-yard at that place. She was got ready for sea, however, by working night and day, and sailed on the 6th, about twelve hours before the Atlantic.

Off Hatteras, on Monday, 8th, the Atlantic ran into a heavy northeast gale, which increased to such a degree that, in order to save the horses on the forward deck, it became necessary to heave the ship to under steam and keep her head to sea for over thirty-six hours. When the gale abated we found ourselves 100 miles out of our course, 138 miles east-southeast from Hatteras.

With all speed possible under the circumstances we made our way to Key West, where, anchoring off the harbor and allowing no other communication with the shore, Colonel Brown, the ordnance officer, Lieutenant Balch, and myself landed by boat at Fort Taylor.

Here, calling the United States judge, Mr. Marvin, the newly-appointed collector and marshal, and the commanding officer of the fort, Major French, to meet Colonel Brown at the fort, the orders and instructions of the President were communicated to these gentlemen, and the commission of marshal for Mr. H. Clapp, intrusted to me for this purpose by the Secretary of State, was delivered to Judge Marvin.

Several secession flags floated from buildings in view of the fort and upon the court-house of the town.

The President’s orders to the authorities at Key West were to tolerate the exercise of no officer in authority inconsistent with the laws and Constitution of the United States, to support the civil authority of the United States by force of arms if necessary, to protect the citizens in their lawful occupations, and in case rebellion or insurrection actually broke out to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, and remove from the vicinity of the fortresses of Key West and Tortugas all dangerous or suspected persons.

Having by restowing much of our cargo made room for some additions, Colonel Brown here drew from Fort Taylor a battery of 12-pounder howitzers and 6-pounder guns, three 10-inch siege mortars for which shells had been embarked at New York, and a supply of ammunition for the field pieces; these, being placed upon a scow, were towed out to the Atlantic anchorage by the Crusader, Captain Craven, and put upon her decks during the night.

Early the next morning, 14th April, we proceeded to the Tortugas, where proper instructions were left with Major Arnold, commanding the place. Four mountain howitzers, with prairie carriages, light and suitable either for the sands of Santa Rosa or for the service upon the covered ways of Fort Pickens, with supplies of fixed ammunition, spherical case and canister, were taken on board.

Twenty carpenters and one overseer, engaged in Washington, had followed me to New York and were already on board the Atlantic.

To assist in the manual labor of disembarking the immense stores, to be landed on an open sea beach exposed to the broad Gulf of Mexico, Colonel Brown, under the ample powers conferred on him by the President, directed Lieutenant Morton, Engineers, to send with the expedition one overseer and twenty of the hired negroes at Fort Jefferson, and skillful with the oar and the rope. By some mistake twenty-one of the negroes embarked, and they proved hardy, willing, and cheerful laborers during the disembarkation.

Lieutenants Reese and McFarland, Engineers, here joined the expedition.

To assist in landing artillery, the attempt was made to tow a scow from Fort Jefferson to Pensacola, but it broke from its fastenings before we left the harbor. It has since been recovered at the fort.

Leaving the harbor of Tortugas after dark on the 14th, forcing our way through a heavy head sea caused by a severe norther, losing all the horse-stalls on the port bow of the steamer, washed away by the sea, though fortunately without destroying any of the horses, we reached the anchorage of the squadron off Pensacola bar at 6 p.m. of the 16th instant. It must then have been known in Pensacola, though concealed from the fort and from those afloat, that Fort Sumter had, after bombardment, surrendered on the 13th.

Communicating with Captain Adams, commanding the squadron, and exhibiting his instructions from the President, Colonel Brown called upon him for boats to make a landing immediately after dark.

The Atlantic proceeded at dark, towing the boats to anchor near the shore, and, while waiting for the boats to come alongside, the signal for attack, two rockets from the fort, was made by Captain Vogdes.

Captain Vogdes, with his company and 110 marines, had landed on the night of the 12th. The orders of General Scott to him to land, received some days before, had not been executed, because unrevoked instructions to Captain Adams from the Secretary of the Navy and the Secretary of War contradicted them. Captain Adams had therefore declined landing the troops until Lieutenant Slemmer officially informed him that he apprehended an attack.

From the signs visible on the mainland and from information received by him, Lieutenant Slemmer on the 12th, being convinced that an attack was imminent, called upon Captain Adams to land the troops and it was done that night.

Major Tower, Engineers, thought that this landing and very stormy weather had deferred the attack. But commotion on shore and movements visible from the fort led them to believe that an attack would be made immediately after the arrival of the Atlantic, and therefore the signal was sent up.

The ditches of the Barrancas were lighted up and much hurrahing was heard.

While the boats were collecting on the Atlantic, Colonel Brown and his staff, taking a boat of the frigate Sabine, under Lieutenant Belknap, of that vessel, pulled into the mouth of the harbor, and we landed on the beach between Forts McRee and Pickens. Passing many sentinels and patrols, we entered Fort Pickens by the north gate, and were gladly welcomed by Captain Vogdes and his officers, who assured us that five thousand men might be expected on shore in a short time.

I returned in the Sabine’s boat to direct the landing of all the men who could be got ashore during the night.

On our way to the Atlantic we met the fleet of boats, and which landed as intended, and put our two hundred men into the fort within a few hours after our arrival.

The night passed off quietly, and the next morning early all the rest of the command, with the exception of the carpenters and laborers and Captain Barry’s artillery company, retained to attend to their horses, were landed on the beach and marched into the fort.

I landed that morning, with Captain Barry and a covering party of men, about five miles from Fort Pickens and reconnoitered the island, determined upon a suitable place for landing the horses and for an intrenched camp out of range of the heaviest artillery on the mainland, and at a point beyond which a boat canal may easily be cut across the island.

During the day and night of the 17th and the morning of the 18th the horses were got ashore. One was drowned alongside by some mismanagement., one got loose, swam twice around the ship before he was caught., and died from exhaustion after landing, and one, turned head over heels by the surf, broke his neck. Four had died and been thrown overboard in the boisterous passage, so that seven out of seventy-three were lost. The rest landed safely, and were at once set to work to haul into the fort the immense stores brought with the expedition.

On the morning of the 17th, while engaged in landing the horses, the Powhatan, which we had passed without seeing her during the voyage, hove in sight. A note from Colonel Brown advised me that in his opinion her entrance into the harbor at that time would bring on a collision, which it was very important to defer until our stores, guns, and ammunition were disposed of.

As the enemy did not seem inclined yet to molest us; as with 600 troops in the fort and three war steamers anchored close inshore there was no danger of a successful attempt at a landing by the enemy, it was evident that it was important to prevent a collision, and her entrance would have uselessly exposed a gallant officer and a devoted crew to extreme dangers.

The circumstances had changed since Captain Porter’s orders had been issued by the President. Knowing the imperative nature of these orders and the character of him who bore them, I feared that it would not be possible to arrest his course; but requesting the commander of the Wyandotte, on board of which I fortunately found myself at the time I received Colonel Brown’s letter, to get under way and place his vessel across the path of the Powhatan, making signal that I wished to speak with him, I succeeded at length, in spite of his changes of course and his disregard of our signals, in stopping this vessel, which steered direct for the perilous channel on which frowned the guns of McRee, Barrancas, and many newly-constructed batteries.

I handed to Captain Porter Colonel Brown’s letter, indorsed upon it my hearty concurrence in its advice, which, under his authority from the Executive, had the force of an order from the President himself, and brought the Powhatan to anchor near the Atlantic, in position to sweep with her guns the landing place and its communications.

The Brooklyn shortly afterwards anchored east of the Atlantic, and the Wyandotte took up position near her.

The landing of so many tons of stores was laborious and tedious. Whenever the surf would permit, it was carried on by the boats of the several vessels, Powhatan, Brooklyn, Wyandotte, Sabine, and St. Louis. The most useful boats engaged were the paddle-box boats of the Powhatan. One of them, armed with a Dahlgren boat howitzer, was kept ready to protect the stores and men on the beach from the guard-boats of the enemy, which would occasionally approach the narrow island from the bay opposite. None of them, however, interrupted the landing.

On the night of the 19th-20th the Illinois arrived bringing Brooks’ and Allen’s companies and 100 recruits and some sixteen stragglers from the companies embarked on the Atlantic. She brought in all 295 men and officers and a full cargo of stores.

On the 23d, having landed all the cargo of the Atlantic, having seen Colonel Brown established in Fort Pickens, I proceeded to sea in the Atlantic to leave dispatches and get coal at Key West, to return her to New York and myself to return to Washington.

The naval store of coal at Key West is small and the Mohawk was about to take her place at the dock to coal and proceed to Fort Pickens to relieve the Wyandotte, almost worn out, having been over one hundred days under steam without opportunity for repair.

The only merchant on the island who had coal for sale, Mr. Tift, sympathizing with those who are in array against his country, refused to sell coal to a steamer in Government employ, and the Atlantic was forced to come to this port as the quickest way of obtaining coal for the voyage to New York.

The seizure of the Star of the West, the issue of letters of marque and reprisal, and the proclamation of the President were not then known to us.

Large requisitions for ordnance and ordnance stores have been made by Colonel Brown. They should be forwarded with all possible dispatch.

The principal batteries constructed against Fort Pickens are beyond the range of the siege 10-inch mortars at that place, and heavy sea-coast 10-inch mortars are much needed. A battery of rifled guns is also wanted.

The distance of the hostile batteries is so great that I think, therefore, though annoying, will do little damage. Rifled 42-pounders will enable the garrison to dismount the 10-inch columbiads which arm the battery west of the light-house, and which are the most formidable opposed to them.

Sea-coast mortars placed in battery outside the fort, but protected by its fire, will cover the whole ground occupied by hostile batteries, and will draw off much of the fire intended for Fort Pickens.

I advised Colonel Brown to place the greater part of his men in an intrenched camp outside. He has now, including marines and 21 mechanics, nearly 1,000 men in the fort.

A favorable spot for camping is found about four miles from the west end of the island. It is beyond the range of the 13-inch sea-coast mortar at the navy-yard. It is overlooked, as is the whole narrow island between it and the fort, by the guns of the steamer—9 and 11 inch guns. A good road can be made between this intrenched camp and the fort, perfectly protected by sand ridges forming natural epaulements from all horizontal fire for nine-tenths of the distance. A boat channel can be easily cut through the island just above it, and this may enlarge to a navigable inlet. Here the men and horses would be healthy, safe from annoyance and from fire.

The fort itself, it appears to me, should be treated like the batteries in front of besieging parallels. Men enough to work the guns in use and to protect it against a sudden dart should be kept in it, and none others exposed to fire.

Thus treated, so long as the United States maintains a naval supremacy off Pensacola, it appears to me that Fort Pickens can be held with little loss of life.

As Fort Sumter, I learned at Key West, has been bombarded and taken, I presume that the farce of peace so long kept up at Pensacola while planting batteries against the United States will soon terminate, and that the entrance of troops, provisions, munitions, and ordnance, by steam and sail, under the guns of our squadron and of our fortress, to be turned against both whenever convenient to do s% will be stopped.

The enemy did not seem to be ready to commence hostilities. They stopped the papers on the night of our arrival, 16th, and of the next mail they allowed, I understand, only two letters to come off to the squadron, both from Southern States. They informed the garrison that Fort Sumter had surrendered without bloodshed; that General Scott had resigned; that Virginia had seceded; that Pennsylvania troops passing through Baltimore to the defense of Washington had been robbed of 8,000 stand of arms, &c., but they continued to work the naval foundery night and day, Sundays included, casting, as was reported, solid shot for their 10-inch and other guns, and they moved artillery from Fort McRee to other positions in preparation for hostilities.

Fort Pickens, Fort Taylor, and Fort Jefferson need much to put them beyond all hazard from the attack of a naval power. Upon these wants I shall have the honor of making a detailed report.

Orders were given by Colonel Brown, as commanding the new Military Department of Florida, for the fortification of the Tortugas Keys, so in connection with vessels of the Navy moved in proper positions, to command the whole anchorage. At present a fleet could enter that harbor and find secure anchorage without exposing a single ship to the fire of Fort Jefferson.

Orders were also given to the commander at Key West and to the Engineer officer, Captain Hunt, to prepare plans for intrenchments to prevent a hostile landing on the island of Key West.

Fort Taylor, with a brick and concrete scarp exposed toward the island, from which it is only 300 yards distant, cannot resist a landing, and is no better fitted to withstand bombardment than Fort Sumter. The burning woodwork of its barracks would soon drive out its garrison.

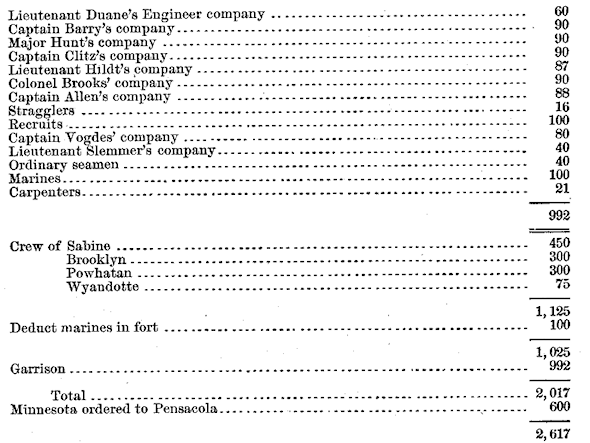

I add an approximate estimate of the United States forces on and about Santa Rosa Island, said to be opposed by about 5,000 to 7,000 men on the mainland. The army on the mainland, however, is probably increased by detachments set at liberty by the taking of Fort Sumter, unless, as is more probable, their armies are both intended for action against Washington City:

The Mohawk, at Key West, is ordered up to relieve the Wyandotte; and the St. Louis is at Key West, believed to be under orders for the Tortugas. Crusader is here to return to Key West in a day or two.

The expedition is under great obligations to the sailors of the fleet, who were ready and untiring in the severe labor of landing horses, ordnance, and stores of all kinds upon the sea beach, exposed at times to a heavy surf, which killed one horse and bilged several boats.

Lieutenants Brown, of the Powhatan, and Lewis, of the Sabine, remained on board the Atlantic for several days, directing the boats and seamen, and were of the greatest assistance to us.

Captain Gray, commanding this steamer, the Atlantic, deserves the thanks of the Government. None could exceed him in efforts for the success of the expedition and for the well-being and comfort of all on board. Night and day he and his crew worked at their posts embarking or disembarking men and stores. His skillful seamanship carried the vessel with the loss of only four horses through a most severe gale which lasted for thirty-six hours, and his watchfulness narrowly saved her from collision with a large vessel at night and during the height of the storm.

I have the honor to be, general, your obedient servant,

M. C. MEIGS,

Captain of Engineers.