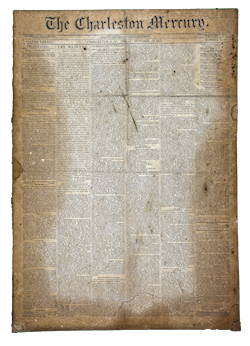

February 26, 1861; The Charleston Mercury

These two officers were placed in similar situations; their conduct has been the reverse, one of the other. Major ANDERSON has become the pet of a party; of Capt. ELSEY we hear nothing. Yet ELSEY has behaved, in a difficult situation, with consummate judgment. ANDERSON has complicated and embarrassed a delicate conjuncture of public affairs by hasty and inconsiderate action.

He was in command at Fort Moultrie. He was ordered to defend himself, if attacked by lawless assemblages. He changed his post, not only orders, but against orders. If ever there was an occasion in which it became an officer to confine himself to a strict obedience of orders, and not to go a hairbreadth beyond them, it was this. He did not obey his orders. He made a stampede from his post, destroyed the public property, and abandoned private stores, for which compensation was afterwards sought in Congress, without a shadow of just reason. There was no cause for his proceedings, except a false rumor of a riotous attack. By the act, he threw himself into an attitude of hostility to the State of South Carolina. He became a political partizan. He mixed himself up in questions with which he had nothing to do. He volunteered little effort of strategy and inaugurated civil war. It was a party movement, and made him immensely popular with a party. He received swords, salutes, and innumerable resolutions of approbation from all the politicians of the North of a certain class. He might well ask himself, under this load of praise, whether he has not done something very foolish, as a certain honest orator of old asked a friend whether he had not said something particularly absurd, when in delivering a speech he was applauded by the mob of listeners.

Now look at ELSEY’S proceedings in a similar position. He holds his post quietly. He listens to no idle rumors about mobs and riotous assailants. When the State of Georgia demands the surrender of his arsenal with an overwhelming force, he appreciates perfectly the exigencies of his position. Under the same orders with ANDERSON, he attempts no work of superogation; no act that would throw him into the arms of one or another political party. He is a soldier, and does his work like a soldier. He marches out of the post which he could no longer hold, and which no principle of honor required him to hold any longer, with bag and baggage. His flag is saluted. He received a receipt from the State authorities of all the Federal property which he leaves. He does not spike his guns, or destroy his ammunition, or break his muskets, or cut down his flagstaff. He simply does his duty, with no flourish. He has received no swords, nor salutes of cannon, nor applauses of pot house politicians or political partizans, nor eulogies from inflammatory party papers; but he has the approbation of every judicious man of all parties, and not an enemy has dared to assail the admirable propriety of his course.

Which of these two men has justly appreciated himself, his duty and the occasion on which he has been obliged to act? It was an unusual occasion. A blunder, therefore, like that of Major ANDERSON’S is pardonable. We can excuse, but we cannot approve.