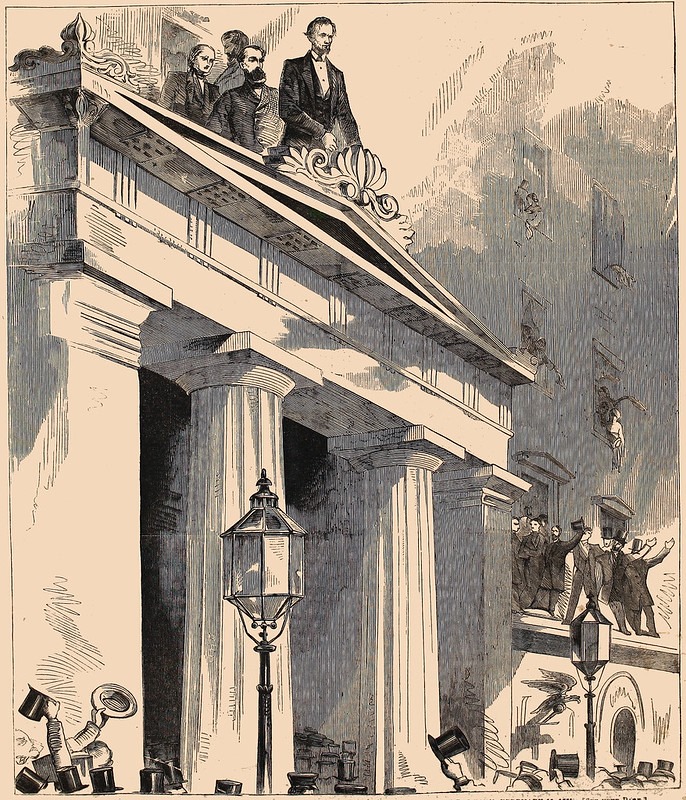

Abraham Lincoln, the President Elect, Addressing the People from the Astor House Balcony

February 19, 1861

Mr. Chairman and Gentlemen:—I am rather an old man to avail myself of such an excuse as I am now about to do, yet the truth is so distinct and presses itself so distinctly upon me that I cannot well avoid it, and that is that I did not understand when I was brought into this room that I was brought here to make a speech. It was not intimated to me that I was brought into the room where Daniel Webster and Henry Clay had made speeches, and where one in my position might be expected to do something like those men, or do something unworthy of myself or my audience. I therefore will beg you to make very great allowance for the circumstances under which I have been by surprise brought before you. Now, I have been in the habit of thinking and speaking for some time upon political questions that have for some years past agitated the country, and if I were disposed to do so, and we could take up some one of the issues as the lawyers call them, and I were called upon to make an argument about it to the best of my ability, I could do that without much preparation. But that is not what you desire to be done here to-night. I have been occupying a position, since the Presidential election, of silence, of avoiding public speaking, of avoiding public writing. I have been doing so because I thought, upon full consideration, that was the proper course for me to take. (Great applause.) I am brought before you now and required to make a speech, when you all approve, more than anything else, of the fact that I have been silent—(loud laughter, cries of “Good—good,” and applause)—and now it seems to me from the response you give to that remark it ought to justify me in closing just here. (Great laughter.) I have not kept silent since the Presidential election from any party wantonness, or from any indifference to the anxiety that pervades the minds of men about the aspect of the political affairs of this country. I have kept silence for the reason that I supposed it was peculiarly proper that I should do so until the time came when, according to the customs of the country, I should speak officially. (Voice, partially interrogative, partially sarcastic, “Custom of the country?”) I heard some gentleman say, “According to the custom of the country;” I alluded to the custom of the President elect at the time of taking his oath of office. That is what I meant by the custom of the country. I do suppose that while the political drama being enacted in this country at this time is rapidly shifting in its scenes, forbidding an anticipation with any degree of certainty to-day what we shall see to-morrow, that it was peculiarly fitting that I should see it all up to the last minute before I should take ground, that I might be disposed by the shifting of the scenes afterwards again to shift. (Applause.) I said several times upon this journey, and I now repeat it to you, that when the time does come I shall then take the ground that I think is right—(interruption by cries of “Good,” “good,” and applause)—the ground I think is right for the North, for the South, for the East, for the West, for the whole country—(cries of “Good,” “Hurrah for Lincoln,” and great applause). And in doing so I hope to feel no necessity pressing upon me to say anything in conflict with the constitution, in conflict with the continued union of these States—(applause)—in conflict with the perpetuation of the liberties of these people—(cheers)—or anything in conflict with anything whatever that I have ever given you reason to expect from me. (Loud cheers.) And now, my friends, have I said enough. (Cries of “No, no,” “Go on,” &c.) Now, my friends, there appears to be a difference of opinion between you and me, and I feel called upon to insist upon deciding the question myself. (Enthusiastic cheers.)

Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Volume 4.