The city was startled on Saturday by the intelligence that the President-elect, instead of proceeding on his journey to Washington from Harrisburg, in accordance with the published programme, on Saturday morning, had left the latter city secretly, on a special train, on Friday night, and returning to Philadelphia, had passed thence, unrecognized, through Baltimore, and was already in the Federal Capital. This step, it appears, was induced by the desire to avoid threatened trouble in Baltimore, and was taken at the earnest solicitation of his friends and leading Republicans in Washington, who had received authentic information that an organized demonstration would be made against him in Baltimore–if, indeed, he were allowed to reach there alive, for it was also feared that an attempt would be made to throw the Presidential train from the track on the Northern Central Railroad. This information, it appears, was imparted to Mr. Lincoln on Thursday night at Philadelphia, and he consented, after considerable hesitation, to the private arrangement which was subsequently carried into effect. He reached Washington early on Saturday morning, and proceeded quietly to his hotel, his arrival being known to but few. He soon afterward, in company with Senator Seward, paid a visit to President Buchanan, and interchanged civilities with him and with other gentlemen of distinction.

The city was startled on Saturday by the intelligence that the President-elect, instead of proceeding on his journey to Washington from Harrisburg, in accordance with the published programme, on Saturday morning, had left the latter city secretly, on a special train, on Friday night, and returning to Philadelphia, had passed thence, unrecognized, through Baltimore, and was already in the Federal Capital. This step, it appears, was induced by the desire to avoid threatened trouble in Baltimore, and was taken at the earnest solicitation of his friends and leading Republicans in Washington, who had received authentic information that an organized demonstration would be made against him in Baltimore–if, indeed, he were allowed to reach there alive, for it was also feared that an attempt would be made to throw the Presidential train from the track on the Northern Central Railroad. This information, it appears, was imparted to Mr. Lincoln on Thursday night at Philadelphia, and he consented, after considerable hesitation, to the private arrangement which was subsequently carried into effect. He reached Washington early on Saturday morning, and proceeded quietly to his hotel, his arrival being known to but few. He soon afterward, in company with Senator Seward, paid a visit to President Buchanan, and interchanged civilities with him and with other gentlemen of distinction.

One Version of the Plot.

The Herald correspondent says: It appears that the plot was concocted in Baltimore, and, being discovered by a detective officer, was by him communicated to two or three leading Republicans, including Mr. Seward and Thurlow Weed. Afterward it was made known to Mr. Judd, of the Presidential party.

“On Thursday last, the intelligence having been privately forwarded to New York, several detectives were at once sent from that city to confer and cooperate with those who had the matter originally in charge. Mr. General Superintendent Kennedy and Commissioner Acton were also on hand. Together they succeeded in ferreting out the details of the conspiracy, and enough has been made known to give it, in the minds of these men, a rank by the side of the most infamous attempts ever made upon human life.

“The exact mode in which the conspirators intended to consummate their designs has not yet transpired; but enough is known to be satisfactory that either an infernal machine was to be placed under the cars or railway, like the Orsini attempt upon Napoleon, or some obstruction placed upon the track whereby the train would be thrown down an embankment at some convenient spot; and that if these failed, then, on the arrival at Baltimore, during the rush and crush of the crowd, as at Buffalo, by knife or pistol, the assassination was to be effected.

“It has also been ascertained that two or three of the conspirators were in New York on Wednesday, the 20th inst., watching the course of events while the President-elect was there.”

Another Version.

The Times correspondent says: On Thursday night after he had retired, Mr. Lincoln was aroused and informed that a stranger desired to see him on a matter of life or death. He declined to admit him unless he gave his name, which he at once did. Of such prestige did the name carry that while Mr. Lincoln was yet disrobed he granted an interview to the caller.

“A prolonged conversation elicited the fact that an organized body of men had determined that Mr. Lincoln should not be inaugurated, and that he should never leave the city of Baltimore alive, if, indeed, he ever entered it.

“The list of the names of the conspirators presented a most astonishing array of persons high in Southern confidence, and some whose fame is not to this country alone.

“Statesmen laid the plan, bankers indorsed it, and adventurers were to carry it into effect. As they understood Mr. Lincoln was to leave Harrisburg at nine o’clock this morning by special train, and the idea was, if possible, to throw the cars from the road at some point where they would rush down a steep embankment and destroy in a moment the lives of all on board. In case of the failure of this project, their plan was to surround the carriage on the way from depot to depot in Baltimore, and assassinate him with dagger or pistol-shot.

“So authentic was the source from which the information was obtained that Mr. Lincoln, after counseling his friends, was compelled to make arrangements which would enable him to subvert the plans of his enemies.

“Greatly to the annoyance of the thousands who desired to call on him last night, he declined giving a reception. The final council was held at eight o’clock.

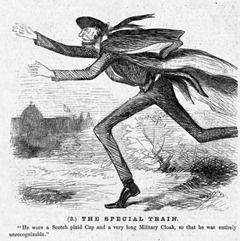

“Mr. Lincoln did not want to yield, and Colonel Sumner actually cried with indignation; but Mrs. Lincoln, seconded by Mr. Judd and Mr. Lincoln’s original informant, insisted upon it, and at nine o’clock Mr. Lincoln left on a special train. He wore a Scotch plaid cap and a very long military cloak, so that he was entirely unrecognizable. Accompanied by Superintendent Lewis and one friend, he started, while all the town, with the exception of Mrs. Lincoln, Colonel Sumner, Mr. Judd, and two reporters, who were sworn to secrecy, supposed him to be asleep.

“The telegraph wires were put beyond the reach of any one who might desire to use them.”

Yet a Third

The Tribune says : “The facts, as given by Superintendent Kennedy are substantially as follows–The police authorities of Baltimore had come to the conclusion that there would be little demonstration of any kind during Mr. Lincoln’s passage through the city. Indeed, as firmly had they become convinced of this, and that there would be no riotous proceedings, that they had determined to employ a force of only twenty men for the special duty of attending to the route of the Presidential cortege through Baltimore. The reason alleged for this course was, that they wished to demonstrate to the country and to the world the law-and-order character of the city.

“This coming to the ears of General Scott, he at once declared that one of two things must be done: either a military escort must be provided for Mr. Lincoln at Baltimore, or there must be a coup de main by which he should be brought through the city unknown to the populace. Under the circumstances, it was thought that the employment or a military escort might create undue excitement, and the cause of its being brought into requisition misinterpreted. The alternative of employing stratagem was therefore determined upon. A messenger–a civilian, and not a military man–carrying three or four letters from men high in position, and one from General Scott, was therefore immediately dispatched to Philadelphia. He had an interview, and delivered his letters sometime toward midnight of last Thursday. It is not known that the fact was communicated to any other person than Mr. Lincoln on that night. Mr. Lincoln, therefore, was apprised of the deviation from the published plan of his journey before he left Philadelphia. The messenger then went on to make arrangements for the special train which conveyed Mr. Lincoln from Harrisburg the next morning.”