“War Diary of a Union Woman in the South” was first edited and published by George Washington Cable in at least two books and across two magazine issues five years apart. At the time, the author chose to remain anonymous.1

“War Diary of a Union Woman in the South” was first edited and published by George Washington Cable in at least two books and across two magazine issues five years apart. At the time, the author chose to remain anonymous.1

Born November 16, 1835 at Charlotte Amalie on St. Thomas, then a part of the Danish West Indies, Dora Richards was of English descent. Her father, Richard Richards, was from Liverpool and her mother, Philomele Huntington, was of English descent through the Huntington family of Connecticut, several members of which were patriots of the American Revolution. One, Samuel Huntington2, was one of the “founding fathers.” Another, Jabez Huntington, Dora’s great grandfather, served as a collector of taxes and member of a commission to purchase firearms. His father-in-law—and Dora’s 2nd great-grandfather—, Jedediah Elderkin, served as Colonel of the 5th regiment of Connecticut Militia throughout the war.3,4,5

After the death of her father, the infant Dora was taken to St. Croix to the home of her maternal grandmother, Mary Huntington, who had freed all of her late-husband’s slaves.

During her childhood on St. Croix, she lived through hurricanes and earthquakes and, at thirteen, experienced a slave uprising and was evacuated with other women and children to ships offshore. The July 1848 insurrection resulted in the emancipation of all Danish West Indies slaves.6

At some point, her mother and siblings had moved to New Orleans, Louisiana. When Dora was about fourteen, she joined her brothers and sisters there to live in the household of a married sister. Her mother had died February 13, 1846 when Dora was eleven.

After graduating from school where her school-girl essays had attracted some attention, Dora was invited by the editors of a New Orleans paper to contribute to their publication. She worked as a teacher and, for a time, provided support for a younger brother.7 At the beginning of her diary in December 1860, she has just turned 25.

On January 18, 1862, in New Orleans’s Trinity Episcopal Church, she married Anderson Miller8, a young lawyer originally from Mississippi. Soon after the wedding, the young couple set out for his home in an Arkansas village, a county seat “on the edge of a lovely lake,9” where Anderson had set up practice with a partner. That spring, the Mississippi flooded, “swamp fever” raged, and the war disrupted food supplies. Plans to return to New Orleans before the Union took it were disrupted when the city fell in April. In July, the couple, with others, journeyed down and across the Mississippi. The plan was to try to get across the lines to New Orleans. Learning the process of procuring a pass would probably result in conscription by the Confederacy for Anderson, the Millers decided to try to find a place in Vicksburg, though they didn’t succeed until November, a month before the beginning of the Vicksburg campaign.

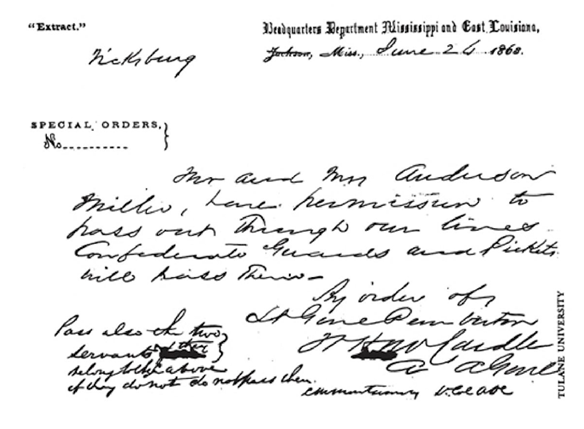

Stuck in Vicksburg during the siege, Dora found herself subjected to a continuous “fiery shower of shells.” The Miller’s attempted to leave the city at least twice. On the 30th of June, they attempted to depart on the basis of Dora’s St. Croix passport, but were turned back when a flag-of-truce officer returned, saying “General Grant says no human being shall pass out of Vicksburg; but the lady may feel sure danger will soon be over. Vicksburg will surrender on the 4th.” On July 2nd (the month on the pass is wrong), Anderson obtained a pass from General Pemberton’s headquarters and they tried to leave by a “miserable, leaky” boat that Anderson had secured. When the boat began to leak rapidly they turned back, taking fire from Confederate pickets before finally landing.10, 11

Dora Miller’s diary, which ends shortly after the fall of Vicksburg, contrasts the opposing forces after the surrender. “A Vicksburg woman (Dora) who watched the entry of Union soldiers pronounced an epitaph on the campaign: ‘What a contrast [these] stalwart, well-fed men, so splendidly set-up and accoutered [were] to . . . the worn men in gray, who were being blindly dashed against this embodiment of modern power.’”12

Her account of the siege of Vicksburg was later published in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine.

Richard Miller died in January, 1867, leaving Dora to support two young sons. She returned to teaching, eventually being appointed to the “chair of science” in the New Orleans Girls’ High School. Her income was augmented through newspaper and magazine articles and doing research for the prolific author and editor, George W. Cable.13 For a time, she wrote the woman’s page for the New Orleans Times-Democrat.14 Her civil war diary was purchased by Cable who was subsequently able to get it published.

Concerned that the school board—and others, in the post-war Southern environment of New Orleans—would learn of the publication of her pro-Union civil war diary in The Century,15, 16 Strange True Stories of Louisiana,17 and Famous Adventures and Prison Escapes of the Civil War,18 Dora’s name was omitted and the initials of most individuals and many names of places were fictitious or omitted.

In 1889, Mrs. Miller was recognized as a talented writer by The Author, a short lived American magazine for literary workers published in Boston.19

By 1891, Dora had lost her New Orleans teaching position20 and was working for the US Census Office.21

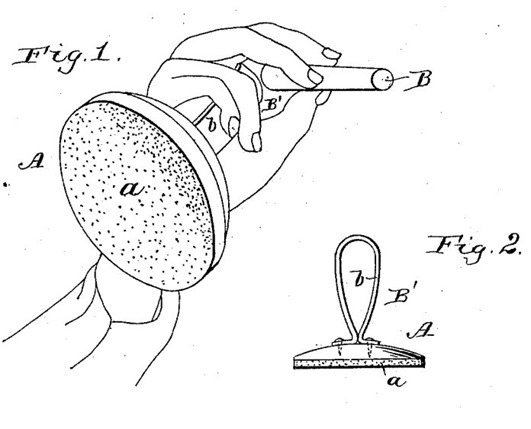

On August 5, 1891, she submitted a patent application called a “Rubber for Blackboards, which was essentially an eraser that could be used with the that was using chalk to write or draw on the blackboard. The patent was granted April 26, 1892.22

Dora’s story about her life in St. Croix and her observations and experiences during the July 1848 slave revolt were published in 1892 as “A West Indian Slave Insurrection” in Scribner’s. The story’s byline was George W. Cable despite her stipulations otherwise when she sold it to him.23 She was merely referred to by her first name in the story as the originator of the story and as its principal character. In The Critic in 1893, the two exchanged public letters-to- the-editor over the issue.24, 25

Dora Miller was found dead in her New Orleans home on the morning of November 7, 1914 just before turning seventy-nine, having outlived both of her adult sons.26

- Dora Richards Miller was a single mother of two boys employed in the school system in post Civil War New Orleans.

- Samuel Huntington was a jurist, statesman, and patriot in the American Revolution from Connecticut. As a delegate to the Continental Congress, he signed the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. He served as President of the Continental Congress from 1779 to 1781, President of the United States in Congress Assembled in 1781 (after the ratification of the Articles of Confederation), chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court from 1784 to 1785, and the 18th Governor of Connecticut from 1786 until his death. (Wikipedia)

- Johnson, S. H. (Compiler). (1912). Lineage Book. (Vol. 36). Washington, DC: National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. p 105. Lineage number 35285 (Google books)

- Mrs. Dora Richards Miller. (1893). F. E. Willard & M. A. Livermore (Eds.), A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life (pp. 504-505). Buffalo, Chicago, New York: Charles Wells Moulton. (online) (Note: this reference was used extensively in writing this modern “biographical sketch.”)

- Daughters of the American Revolution online search December 5, 2020(Note: other information from the search is also included in this “sketch”).

- Danish West Indies slave emancipation – Wikipedia

- The younger brother was likely a half-sibling as her father had died when Dora was an infant. Her mother may have remarried while Dora was living with her maternal grandmother on St. Croix.

- Hoehling, A. A. (1996). Vicksburg: 47 days of siege. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 40:

A young bride, Mrs. Anderson Miller, found that she was subjected to a continuous “fiery shower of shells.” The former Dora Richards, of St. Croix in the West Indies, Mrs. Miller had been married on January 18, 1862, in Trinity Episcopal Church, New Orleans. Then, with her lawyer-husband, Dora, who had long thought of herself as “a rather lonely young girl,” had gone on to a small town in Arkansas, Anderson’s home. She became lonelier yet. Nor could they escape the war in Arkansas.

The Millers then moved east to Vicksburg and found disruption even more acute. They arrived in time for the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou. Not only was there no law practice in the embattled city but the couple soon became “utterly cut off from the world.” - This may have been Lake Village, the county seat of Chicot County. Lake Village is located on Lake Chicot, a Mississippi River oxbow lake. (Lake Village, Arkansas – Wikipedia)

- Dora Miller’s diary.

- Hoehling (1996)

- McPherson, J. M. (1988). The Oxford History of the United States, Volume VI: Battle Cry of Freedom; the Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 637

- Turner, A. (1966). George W. Cable – A Biography. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press.

- Hoehling (1996)

- Miller, D. (anonymously) (1885, September). A Woman’s Diary of the Siege of Vicksburg (G. W. Cable, Ed.). Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, XXX(5), 767-775.

- Miller, D. (anonymously) (1889, October). War Diary of a Union Woman in the South (G. W. Cable, Ed.). The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, 38(6), 931-946.

- Cable, G. W. (Ed.). (1898). War Diary of a Union Woman in the South. In D. Miller (Author, anonymously), Strange True Stories of Louisiana (pp. 261-350). New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Cable, G. W. (Ed.). (1911). War Diary of a Union Woman in the South (G. Cable, Ed.). In D. Miller (Author, anonymously), Famous Adventures and Prison Escapes of the Civil War (pp. 1-85). New York: The Century Company.

- Hills, W. H. (Ed.). (1889, December 15). Literary News and Notes. The Author, 1(12), 192. “Mrs. Dora R. Miller. of New Orleans. is a talented writer, though as yet not very well known. She is a contributor to Lippincott’s, the Century, and other standard magazines. “The Diary of a Southern Woman.” which appeared in the August Century, [It was actually the October issue and was titled War Diary of a Union Woman in the South] under the editorship of George W. Cable, was written by Mrs. Miller, though the article was presented in a rather ambiguous form, which may have misled the public as to its authorship. Mrs. Miller should be recognized and a place assured her among the talented and remunerated writers of the present day. The interest evinced in this writer by George W. Cable should alone prove her claim to talents of a high order. She has occupied a distinguished position as teacher in New Orleans for many years. successfully and meritoriously ?lling the Chair of Science in the High School and locally known as contributor to scienti?c and educational journals. Such intellects as Mrs. Miller’s should be recognized. and the right hand of fellowship extended by more experienced writers.

- Turner (1966)

- United States, Department of the Interior. (1892). Official Register of the United States (p. 762). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Retrieved December 6, 2020, from https://books.google.com/books?id=TqRLAQAAMAAJ The Official Register cited is a compilation of officers and employees in the civil, military, and naval service on July 1, 1891. Mrs. Miller is listed under the Census Office with a compensation of $600 (~$17, 168 in 2020).

- Miller, D. (1892). U.S. Patent No. 473,558. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Miller, D. (1892, December). A West Indian Slave Insurrection (G. W. Cable, Ed.). Scribner’s Magazine, 12 (6), 709-720. [Cable had purchased the story from Mrs. Miller for $50 (equivalent to about $2740 in 2020)]. (Note: Dora Miller stated in The Critic, [March 11, 1893] “… if he still wished to buy it, could have it if he would name me as author.” Cable said that he would. He didn’t. The byline, as published, was his. She is merely named in the story as the principle character, Dora)

- Cable, G. W. (1893, February 4). Mr. Cable as an Editor. The Critic, A Weekly Review of Literature and the Arts,, 9, 63-64. “To the Editors of the Critic.”

- Miller, D. R. (1893, March 18). Mr. Cable as Editor Again. The Critic, A Weekly Review of Literature and the Arts, 19, 167-168. “To the Editors of the Critic.”

- Hoehling (1996)