“I was here when the Star of the West was fired on,” the Lieutenant told us. “We only had powder for two hours. Anderson could have put us out in a short time, if he had chosen.”

In January 1861, a Connecticut civilian named John William De Forest returned to Charleston to visit after an extended absence. Originally published in The Atlantic Monthly, April 1861

Stranded—A Visit to Fort Moultrie

Stranded—A Visit to Fort Moultrie

The following material contains wording that is offensive to many in the world of today. However, the work is provided unedited for its historical content and context.

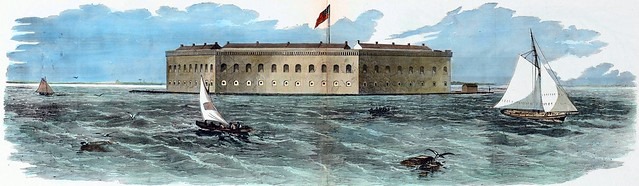

After passing six days in Charleston, hearing much that was extraordinary, but seeing little, I left in the steamer Columbia for New York. The main opening to the harbor, or Ship Channel, as it is called, being choked with sunken vessels, and the Middle Channel little known, our only resource for exit was Maffitt’s Channel, a narrow strip of deep water closely skirting Sullivan’s Island. It was half-past six in the morning, slightly misty and very quiet. Passing Fort Sumter, then Fort Moultrie, we rounded a low break-water, and attempted to take the channel. I have heard a half-dozen reasons why we struck; but all I venture to affirm is that we did strike. There was a bump; we hoped it was the last:—there was another; we hoped again:—there was a third; we stopped. The wheels rolled and surged, bringing the fine sand from the bottom and changing the green waters to yellow; but the Columbia remained inert under the gray morning sky, close alongside of the brown, damp beach of Sullivan’s Island. There was only a faint breeze, and a mere ripple of a sea; but even those slight forces swung our stern far enough toward the land to complete our helplessness. We lay broadside to the shore, in the centre of a small crescent or cove, and, consequently, unable to use our engines without forcing either bow or stern higher up on the sloping bottom. The Columbia tried to advance, tried to back water, and then gave up the contest, standing upright on her flat flooring with no motion beyond an occasional faint bumping. The tug-boat Aid, half a mile ahead of us, cast off from the vessel which it was taking out, and came to our assistance. Apparently it had been engaged during the night in watching the harbor; for on deck stood a score of volunteers in gray overcoats, while the naval-looking personage with grizzled whiskers who seemed to command was the same Lieutenant Coate who transferred the revenue-cutter Aiken from the service of the United States to that of South Carolina. The Aid took hold of us, broke a large new hawser after a brief struggle, and then went up to the city to report our condition.

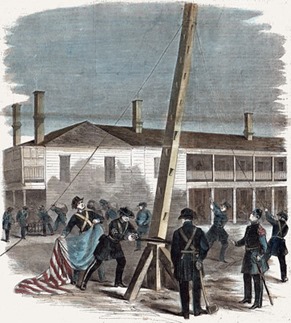

Columbia Ashore on Sullivan’s Island, January 1861,

by William Waud of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

The morning was lowery, with driving showers running through it from time to time, and an atmosphere penetratingly damp and cheerless. On the beach two companies of volunteers were drilling in the rain, no doubt getting an appetite for breakfast. Without uniforms, their trousers tucked into their boots, and here and there a white blanket fastened shawl-like over the shoulders, they looked, as one of our passengers observed, like a party of returned Californians. Their line was uneven, their wheeling excessively loose, their evolutions of the simplest and yet awkwardly executed. Evidently they were newly embodied, and from the country; for the Charleston companies are spruce in appearance and well drilled. Half a dozen of them, who had been on sentinel duty during the night, discharged their guns in the air,—a daily process, rendered necessary by the moist atmosphere of the harbor at this season; and then, the exercise being over, there was a general scamper for the shelter of a neighboring cottage, low-roofed and surrounded by a veranda after the fashion of Sullivan’s Island. Within half an hour they reappeared in idle squads, and proceeded to kill the heavy time by staring at us as we stared at them. One individual, learned in sea-phrase, insulted our misfortune by bawling, “Ship ahoy!” A fellow in a red shirt, who looked more like a Bowery bhoy than like a Carolinian, hailed the captain to know if he might come aboard; whereupon he was surrounded by twenty others, who appeared to question him and confound him until he thought it best to disappear unostentatiously. I conjectured that he was a hero of Northern birth, who had concluded to run away, if he could do it safely.

When we tired of the volunteers, we looked at the harbor and its inanimate surroundings. A ship from Liverpool, a small steamer from Savannah, and a schooner or two of the coasting class passed by us toward the city during the day, showing to what small proportions the commerce of Charleston had suddenly shrunk. On shore there seemed to be no population aside from the volunteers. Sullivan’s Island is a summer resort, much favored by Charlestonians in the hot season, because of its coolness and healthfulness, but apparently almost uninhabited in winter, notwithstanding that it boasts a village called Moultrieville. Its hundred cottages are mostly of one model, square, low-roofed, a single story in height, and surrounded by a veranda, a portion of which is in some instances in-closed by blinds so as to add to the amount of shelter. Paint has been sparingly used, when applied at all, and is seldom renewed, when weather-stained. The favorite colors, at least those which most strike the eye at a distance, are green and yellow. The yards are apt to be full of sand-drifts, which are much prized by the possessors, with whom it is an object to be secured from high tides and other more permanent aggressions of the ocean. The whole island is but a verdureless sand-drift, of which the outlines are constantly changing under the influence of winds and waters. Fort Moultrie, once close to the shore, as I am told, is now a hundred yards from it; while, half a mile off, the sea flows over the site of a row of cottages not long since washed away. Behind Fort Moultrie, where the land rises to its highest, appears a continuous foliage of the famous palmettos, a low palm, strange to the Northern eye, but not beautiful, unless to those who love it for its associations. Compared with its brothers of the East, it is short, contracted in outline, and deficient in waving grace.

The chill mist and drizzling rain frequently drove us under cover. While enjoying my cigar in the little smoking-room on the promenade-deck, I listened to the talk of four players of euchre, two of them Georgians, one a Carolinian, and one a pro-slavery New-Yorker.

“I wish the Capin would invite old Greeley on board his boat in New York,” said the Gothamite, “and then run him off to Charleston. I’d give ten thousand dollars towards paying expenses; that is, if they could do what they was a mind to with him.”

“I reckon a little more ‘n ten thousand dollars ‘d do it,” grinned Georgian First.

“They ‘d cut him up into little bits,” pursued the New Yorker.

“They ‘d worry him first like a cat does a mouse,” added the Carolinian.

“I’d rather serve Beecher or—what ‘s his name?— Cheever, that trick,” observed Georgian Second. “It’s the cussed parsons that’s done all the mischief. Who played that bower? Yours, eh? My deal.”

“I want to smash up some of these dam’ Black Republicans,” resumed the New-Yorker. “I want to see the North suffer some. I don’t care, if New York catches it. I own about forty thousand dollars’ worth of property in _______ Street, and I want to see the grass growing all round it. Blasted, if I can get a hand any way!”

“I say, we should be in a tight place, if the forts went to firing now,” suggested the Carolinian. “Major Anderson would have a fair chance at us, if he wanted to do us any harm.”

“Damn Major Anderson!” answered the New Yorker. “I’d shoot him myself, if I had a chance. I’ve heard about Bob Anderson till I ‘m sick of it.”

Of this fashion of conversation you may hear any desired amount at the South, by going among the right sort of people. Let us take it for granted, without making impertinent inquiry, that nothing of the kind is ever uttered in any other country, whether in pothouse or parlor. I suppose that such remarks seem very horrid to ladies and other gentle-minded folk, who perhaps never heard the like in their lives, and imagine, when they see the stuff on paper, that it is spoken with scowling brows, through set teeth, and out of a heart of red-hot passion. The truth is, that these ferocious phrases are generally drawled forth in an ex-officio tone, as if the speaker were rather tired of that sort of thing, meant nothing very particular by it, and talked thus only as a matter of fashion. It will be observed that the most violent of these politicians was a New Yorker. I am inclined to pronounce, also, that the two Georgians were by birth New Englanders. The Carolinian was the most moderate of the company, giving his attention chiefly to the game and throwing out his one re-mark concerning the worrying of Greeley with an air of simply civil assent to the general meaning of the conversation, as an exchange of anti-abolition sentiments. “If you will play that card,” he seemed to say, “I follow suit as a mere matter of course.”

There was a second attempt to haul us off at sunset, and a third in the morning, both unsuccessful. Each tide, though stormless, carried the Columbia a little higher up the beach; and the tugs, trying singly to move her, only broke their hawsers and wasted precious time. Fortunately, the sea continued smooth; so that the ship escaped a pounding. On Saturday, at eleven, twenty-eight hours after we struck, all hope of getting off without discharging cargo having been abandoned, we passengers were landed on Sullivan’s Island, to make our way back to Charleston. Our baggage was forwarded to the ferry in carts, and we followed at leisure on foot. In company with Georgian First and a gentleman from Brooklyn, I strolled over the sand-rolls, damp and hard now with a week’s rain, passed one or two of the tenantless summer-houses, and halted beside the glacis of Fort Moultrie. I do not wonder that Major Anderson did not consider his small force safe within this fortification. It is overlooked by neighboring sand-hills and by the houses of Moultrieville, which closely surround it on the land side, while its ditch is so narrow and its rampart so low that a ladder of twenty-five feet in length would reach from the outside of the former to the summit of the latter. A fire of sharp-shooters from the commanding points, and two columns of attack, would have crushed the feeble garrison. No military movement could be more natural than the retreat to Fort Sumter. What puzzles one, especially on the spot, and what nobody in Charleston could explain to me, is the fact that this manœuvre could be executed unobserved by the people of Moultrieville, few as they are, and by the guard-boats which patrolled the harbor.

On the eastern side of the fort two or three dozen negroes were engaged in filling canvas bags with sand, to be used in forming temporary embrasures. One lad of eighteen, a dark mulatto, presented the very remarkable peculiarity of chest-nut hair, only slightly curling. The others were nearly all of the true field-hand type, aboriginal black, with dull faces, short and thick forms, and an air of animal contentment or at least indifference. They talked little, but giggled a great deal, snatching the canvas bags from each other, and otherwise showing their disbelief in the doctrine of all work and no play. When the barrows were sufficiently filled to suit their weak ideal of a load, a procession of them set off along a plank cause-way leading into the fort, observing a droll semblance of military precision and pomp, and forcing a passage through lounging unmilitary buckras with an air of, “Out of de way, Ole Dan Tacker!” We glanced at the yet unfinished ditch, half full of water, and walked on to the gateway. A grinning, skipping negro drummer was showing a new pair of shoes to the tobacco-chewing, jovial youth who stood, or rather sat, sentinel.

“How ‘d you get hold of them?” asked the latter, surveying the articles admiringly.

“Got a special order from the Cap’m fur ‘um. That ee way to do it. Won’t wet through, no matter how it rain. He, he! I ‘m all right now.”

Here he showed ivory to his ears, cut a caper, and danced into the fort.

“D-a-m’ nigger!” grinned the sentinel, approvingly, looking at us to see if we also enjoyed the incident. Thus introduced to the temporary guardian of the fort, we told him that we were from the Columbia,—which he was glad to hear of; wanting to know if she was damaged, how she went ashore, whether she could get off, etc., etc. He was a fair specimen of the average country Southerner, lounging, open to address, and fond of talk.

“I’ve no authority to let’ you in,” he said, when we asked that favor; “but I’ll call the corporal of the guard.”

“If you please.”

“Corporal of the guard!”

Appeared the corporal, who civilly heard us, and went for the lieutenant of the guard. Presently a blonde young officer, with a pleasant face, somewhat Irish in character, came out to us, raising his forefinger in military salute.

“We should like to go into the fort, if it is proper,” I said. “We ask hospitality the more boldly, because we are ship-wrecked people.”

“It is against the regulations. However, I venture to take the responsibility,” was the obliging answer.

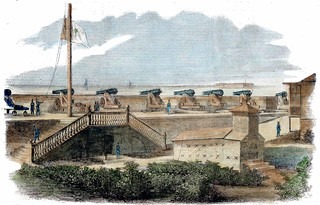

We passed in, and wandered unwatched for half an hour about the irregular, many-angled fortress. One-third of the interior is occupied by two brick barracks, covered with rusty stucco, and by other brick buildings, as yet incomplete, which I took to be of the nature of magazines. On the walls, gaping landward as well as seaward, are thirty or thirty-five iron cannon, all en barbette, but protected toward the harbor by heavy piles of sand-bags, fenced up either with barrels of sand or palmetto-logs driven firmly into the rampart. Four eight-inch columbiads, carrying sixty-four pound balls, pointed at Fort Sumter. Six other heavy pieces, Paixhans, I believe, faced the neck of the harbor. The remaining armament is of lighter calibre, running, I should judge, from forty-twos down to eighteens. Only one gun lay on the ground destitute of a carriage. The place will stand a great deal of battering; for the walls are nearly hidden by the sand-covered glacis, which would catch and smother four point-blank shots out of five, if discharged from a distance. Against shells, however, it has no resource; and one mortar would make it a most unwholesome residence.

We passed in, and wandered unwatched for half an hour about the irregular, many-angled fortress. One-third of the interior is occupied by two brick barracks, covered with rusty stucco, and by other brick buildings, as yet incomplete, which I took to be of the nature of magazines. On the walls, gaping landward as well as seaward, are thirty or thirty-five iron cannon, all en barbette, but protected toward the harbor by heavy piles of sand-bags, fenced up either with barrels of sand or palmetto-logs driven firmly into the rampart. Four eight-inch columbiads, carrying sixty-four pound balls, pointed at Fort Sumter. Six other heavy pieces, Paixhans, I believe, faced the neck of the harbor. The remaining armament is of lighter calibre, running, I should judge, from forty-twos down to eighteens. Only one gun lay on the ground destitute of a carriage. The place will stand a great deal of battering; for the walls are nearly hidden by the sand-covered glacis, which would catch and smother four point-blank shots out of five, if discharged from a distance. Against shells, however, it has no resource; and one mortar would make it a most unwholesome residence.

“What ‘s this?” asked a volunteer, in homespun gray uniform, who, like ourselves, had come in by courtesy.

“What ‘s this?” asked a volunteer, in homespun gray uniform, who, like ourselves, had come in by courtesy.

“That’s the butt of the old flag staff,” answered a comrade. “Cap’n Foster cut it down before he left the fort, damn him! It was a dam’ sneaking trick. I’ve a great mind to shave off a sliver and send it to Lincoln.”

The idea of getting a bit of the famous staff as a memento struck me, and I attempted to put it in practice; but the exceedingly tough pitch-pine defied my slender pocket-knife.

“Jim, cut the gentleman a piece,” said one of the volunteers. Jim drew a toothpick a foot long and did me the favor, for which I here repeat my thanks to him.

They were good-looking, healthy fellows, these two, like most of their comrades, with a certain air of frank gentility and self-respect about them, being probably the sons of well-to-do planters. It would be a great mistake to suppose that the volunteers are drawn, to any extent whatever, from the “poor white trash.” The secession movement, like all the political action of the State at all times, is independent of the crackers, asks no aid nor advice of them, and, in short, ignores them utterly.

“I was here when the Star of the West was fired on,” the Lieutenant told us. “We only had powder for two hours. Anderson could have put us out in a short time, if he had chosen.”

“How rapidly can these heavy guns be fired?”

“About ten times an hour.”

“Do you think the defences will protect the garrison against a bombardment?” “I think the palmetto stockades will answer. I don’t know about that enormous pile of barrels, however. If a shot hits the mass on the top, I am afraid it will come down, bags and barrels together, bury the gun and perhaps the gunners.”

“What if Sumter should open now?” I suggested.

“We should be here to help,” answered the Georgian.

“We should be here to run away,” amended my comrade from Brooklyn. “Well, I suppose we should be of mighty little use, and might as well clear out,” was the sober second-thought of the Georgian.

Having satisfied our curiosity, we thanked the Lieutenant and left Fort Moultrie. The story of our visit to it excited much surprise, when we recounted it in the city. Members of the Legislature and other men high in influence had desired the privilege, but had not applied for it, expecting a repulse.

A walk down a winding street, bordered by scattered cottages, inclosed by brown board-fences or railings, and tracked by a horse-railroad built for the Moultrie House, led us to the ferry-wharf, where we found our baggage piled together, and our fellow-passengers wandering about in a state of bored expectation. Sullivan’s Island in winter is a good spot for an economical man, inasmuch as it presents no visible opportunities of spending money. There were houses of refreshment, as we could see by their signs; but if they did business, it was with closed doors and barred shutters. After we had paid a newsboy five cents for the Mercury, and five more for the Courier, we were at the end of our possibilities in the way of extravagance. At half- past one arrived the ferry-boat with a few passengers, mostly volunteers, and a deck-load of military stores, among which I noticed Boston biscuit and several dozen new knapsacks. Then, from the other side, came the “dam’ nigger,” that is to say, the drummer of the new shoes, beating his sheepskin at the head of about fifty men of the Washington Artillery, who were on their way back to town from Fort Moultrie. They were fine-looking young fellows, mostly above the middle size of Northerners, with spirited and often aristocratic faces, but somewhat more devil-may-care in expression than we are accustomed to see in New England. They poured down the gangway, trailed arms, ascended the promenade-deck, ordered arms, grounded arms, and broke line. The drill struck rue as middling, which may be owing to the fact that the company has lately increased to about two hundred members, thus diluting the old organization with a large number of new recruits. Military service at the South is a patrician exercise, much favored by men of “good family,” more especially at this time, when it signifies real danger and glory.

Our rajpoots having entered the boat, we of lower caste were permitted to follow. At two o’clock we were steaming over the yellow waters of the harbor. The volunteers, like everybody else in Charleston, discussed Secession and Fort Sumter, considering the former as an accomplished fact, and the latter as a fact of the kind called stubborn. They talked uniform, too, and equipments, and marksmanship, and drinks, and cigars, and other military matters. Now and then an awkwardly folded blanket was taken from the shoulders which it disgraced, refolded, packed carefully in its covering of India-rubber, and strapped once more in its place, two or three generally assisting in the operation. Presently a firing at marks from the upper deck commenced. The favorite target was a conical floating buoy, showing red on the sunlit surface of the harbor, some four hundred yards away. With a crack and a hoarse whiz the minié-balls flew towards it, splashing up the water where they first struck and then taking two or three tremendous skips before they sank. A militiaman from New York city, who was one of my fellow-passengers, told me that he “never saw such good shooting.” It seemed to me that every sixth ball either hit the buoy full, or touched water but a few yards this side of it, while not more than one in a dozen went wild.

“It is good for a thousand yards,” said a volunteer, slapping his bright, new piece, proudly.

A favorite subject of argument appeared to be whether Fort Sumter ought to be attacked immediately or not. A lieutenant standing near me talked long and earnestly regarding this matter with a civilian friend, breaking out at last in a loud tone, —

“Why, good Heaven, Jim! do you want that place to go peaceably into the hands of Lincoln?

“No, Fred, I do not. But I tell you, Fred, when that fort is attacked, it will be the bloodiest day,—the bloodiest day! — the bloodiest — !I”

And here, unable to express himself in words, Jim flung his arms wildly about, ground his tobacco with excitement, spit on all sides, and walked away, shaking his head, I thought, in real grief of spirit.

We passed close to Fort Pinckney, our volunteers exchanging hurrahs with the garrison. It is a round, two-storied, yellow little fortification, standing at one end of a green marsh known as Shute’s Folly Island. What it was put there for no one knows: it is too close to the city to protect it; too much out of the harbor to command that. Perhaps it might keep reinforcements for Anderson from coming down the Ashley, just as the guns on the Battery were supposed to be intended to deter them from descending the Cooper.

On the wharf of the ferry three drunken volunteers, the first that I had seen in that condition, brushed against me. The nearest one, a handsome young fellow of six feet two, half turned to stare back at me with a—

“How are ye, Cap’m ? Gaw damn ye! Haw, haw, awl”— and reeled onward, brimful of spirituous good-nature.

Four days more had I in Charleston, waiting from tide to tide for a chance to sail to New York, and listening from hour to hour for the guns of Fort Sumter. Sunday was a day of excitement, a report spreading that the Floridians had attacked Fort Pickens, and the Charlestonians feeling consequently bound in honor to fight their own dragon. Groups of earnest men talked all day and late into the evening under the portico and in the basement-rooms of the hotel, besides gathering at the corners and strolling about the Battery. “We must act” “We cannot delay.” “We ought not to submit.” Such were the phrases that fell upon the ear oftenest and loudest.

As I lounged, after tea, in the vestibule of the reading-room, an eccentric citizen of Arkansas varied the entertainment. A short, thin man, of the cracker type, swarthy, long-bearded, and untidy, he was dressed in well-worn civilian costume, with the exception of an old blue coat showing dim remnants of military garniture. Reeling up to a gentleman who sat near me, he glared stupidly at him from beneath a broad-brimmed hat, demanding a seat mutely, but with such eloquence of oscillation that no words were necessary. The respectable person thus addressed, not anxious to receive the stranger into his lap, rose and walked away, with that air of not having seen anything so common to disconcerted people who wish to conceal their disturbance. Into the vacant place dropped the stranger, stretching out his feet, throwing his head back against the wall, and half closing his eyes with the drunkard’s own leer of self-sufficiency. During a few moments of agonizing suspense the world waited. Then from those whiskey-scorched and tobacco-stained lips came a long, shrill “Yee-p!”

It was his exordium; it demanded the attention of the company; and though he had it not, he continued:

“I ‘m an Arkansas man, I am. I ‘m a big su-gar planter, I am. All right! Go a’ead! I own fifty niggers, I do.

Yee-p!”

He lifted both feet and slammed them on the floor energetically, pausing for a reply. He had addressed all men; no one responded, and he went on : —

“I’m for straightout, immedit shession, I am. I go for ‘staining coursh of Sou’ Car’lina, I do. I ‘m ready to fight for Sou’ Car’lina. I’m a Na-po-le-on Bonaparte. All right! Go a’ead! Yee-p! Fellahs don’t know me here. I ‘m an Arkansas man, I am. Sou’ Car’lina won’t kill an Arkansas man. I’m an immedit shessionist. Hurrah for Sou’ Car’lina! All right! Yee-p I”

There was a lingering, caressing accent on his “I am,” which told how dear to him was his individuality, drunk or sober. He looked at no one; his hat was drawn over his eyes; his hands were deep in his pockets; his feet did all needful gesturing. I stepped in front of him to get a fuller view of his face, and the action aroused his attention. He surveyed my gray Inverness wrapper and gave me a chuckling nod of approbation.

“How are ye, Bub ? I like that blanket, I do.”

In spite of this noble stranger’s good-will and prowess, we still found Fort Sumter a knotty question. In a country which for eighty years has not seen a shot fired in earnest, it is not wonderful that a good deal of ignorance should exist concerning military matters, and that second-class plans should be hatched for taking a first-class fortification. While I was in Charleston, the most popular proposition was to bombard continuously for two whole days and nights, thereby demoralizing the garrison by depriving it of sleep and causing it to surrender at the first attempt to escalade. Another plan, not in general favor, was to smoke Anderson out by means of a raft covered with burning mixtures of a chemical and bad-smelling nature. Still another, with perhaps yet fewer adherents, was to advance on all sides in such a vast number of rowboats that the fort could not sink them all, whereupon the survivors should land on the wharf and proceed to take such further measures as might be deemed expedient. The volunteers from the country always arrived full of faith and defiance. “We want to get a squint at that Fort Sumter,” they would say to their city friends. “We are going to take it. If we don’t plant the palmetto on it, it ‘s because there ‘s no such tree as the palmetto.” Down the harbor they would go in the ferry-boats to Morris or Sullivan’s Island. The spy-glass would be brought out, and one after another would peer through it at the object of their enmity. Some could not sight it at all, confounded the instrument, and fell back on their natural vision. Others, more lucky, or better versed in telescopic observations, got a view of the fortress, and perhaps burst out swearing at the evident massiveness of the walls and the size of the columbiads.

“Good Lord, what a gun!” exclaimed one man. “D’ ye see that gun ? What an almighty thing ! I’ll be ———, if I ever put my head in front of it!”

The difficulties of assault were admitted to be very great, considering the bad footing, the height of the ramparts, and the abundant store of muskets and grenades in the garrison. As to breaches, nobody seemed to know whether they could be made or not. The besieging batteries were neither heavy nor near, nor could they be advanced as is usual in regular sieges, nor had they any advantage over the defence except in the number of gunners, while in regard to position and calibre they were inferior. To knock down a wall nearly forty feet high and fourteen feet thick at a distance of more than half a mile seemed a tough undertaking, even when unresisted. It was discovered also that the side of the fortification towards Fort Johnstone, its only weak point, had been strengthened so as to make it bomb-proof by means of interior masonry constructed from the stones of the landing-place. Then nobody wanted to knock Fort Sumter down, inasmuch as that involved either the labor of building it up again, or the necessity of going without it as a harbor-defence. Finally, suppose it should be attacked and not taken? Really, we unlearned people in the art of war were vastly puzzled as we thought this whole matter over, and we sometimes doubted whether our superiors were not almost equally bothered with ourselves.

This fighting was a sober, sad subject; and yet at times it took a turn toward the ludicrous. A gentleman told me that he was present when the steamer Marion was seized with the intention of using her in pursuing the Star of the West. A vehement dispute arose as to the fitness of the vessel for military service.

“Fill her with men, and put two or three eighteen-pounders in her,” said the advocates of the measure.

“Where will you put your eighteen-pounders?” demanded the opposition. “On the promenade-deck, to be sure.” “Yes, and the moment you fire one, you’ll see it go through the bottom of the ship, and then you’ll have to go after it.” During the two days previous to my second and successful attempt to quit Charleston, the city was in full expectation that the fort would shortly be attacked. News had arrived that Federal troops were on their way with reinforcements. An armed steamer had been seen off the harbor, both by night and day, making signals to Anderson. The Governor went clown to Sullivan’s Island to inspect the troops and Fort Moultrie. The volunteers, aided by negroes and even negro women, worked all night on the batteries. Notwithstanding we were close upon race-week, when the city is usually crowded, the streets had a deserted air, and nearly every acquaintance I met told me he had been down to the islands to see the preparations. Yet the whole excitement, like others which had preceded, ended even short of smoke. News came that reinforcements had not been sent to Anderson; and the destruction of that most inconvenient person was once more postponed. People fell back on the old hope that the Government would be brought to listen to reason,—that it would give up to South Carolina what it could not keep from her with justice, — that it would grant, in short, the incontrovertible right of peaceable secession. For, in the midst of all these labors and terrors, this expense and annoyance, no one talked of returning into the Union, and all agreed in deprecating compromise.

Once more, this time in the James Adger, I set sail from Charleston. The boat lost one tide, and consequently one day, because at the last moment the captain found himself obliged to take out a South Carolina clearance. As I passed down the harbor, I counted fourteen square-rigged vessels at the wharves, and one lying at anchor, while three others had just passed the bar, outward-bound, and two were approaching from the open sea. Deterred from the Ship Channel by the sunken schooners, and from Maffitt’s Channel by the fate of the Columbia, we tried the Middle Channel, and glided over the bar without accident.

“Sailing to Charleston is very much like going foreign,” I said to a middle-aged sea-captain whom we numbered among our passengers. “What with heaving the lead, and doing without beacons, and lying off the coast o’ nights, it makes one think of trading to new countries.”

I had, it seems, unintentionally pulled the string which jerked him. Springing up, he paced about excitedly for a few moments, and then broke out with his story.

“Yes, —I know it,—I know as much about it as anybody, I reckon. I lay off there nine days in a nor’easter and lost my anchors; and here I am going on to New York to buy some more; and all for those cursed Black Republicans!”

In South Carolina they see but one side of the shield, — which is quite different, as we know, from the custom of the rest of mankind.