“We shall never attack Fort Sumter,” said one gentleman. “Don’t you see why? I have a son in the trenches, my next neighbor has one, everybody in the city has one. Well, we shan’t let our boys fight; we can’t bear to lose them. We don’t want to risk our handsome, genteel, educated young fellows against a gang of Irishmen, Germans, British deserters, and New York roughs, not worth killing, and yet instructed to kill to the best advantage. We can’t endure it, and we shan’t do it.”

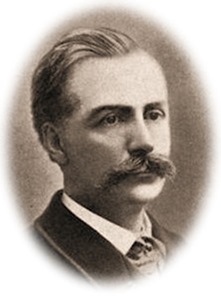

In January 1861, a Connecticut civilian named John William De Forest returned to Charleston to visit after an extended absence. Originally published in The Atlantic Monthly, April 1861

Are all the South Carolinians disunionists? It s eemed so when I was there in January, 1861, and yet it did not seem so when I was there in 1855 and ’56. At that time you could find men in Charleston who held that the right of secession was but the right of revolution, of rebellion,—well enough, if successful, but inductive to hanging, if unfortunate. Now those same men nearly all argue for the right of peaceable secession, declaring that the State has a right to go out at will, and that the Federal Government has no right to coerce or punish it. These turncoats are the sympathetic, who are carried away by a rush of popular enthusiasm, and the fearful or peaceable, who dread or dislike violence. Let us see how a timid Unionist can be converted into an advocate of the right of secession. Let us suppose a boat with three men on board, which is hailed by a revenue-cutter, with a threat of firing, if she does not come to. Two of these men believe that the revenue-officer is performing a legal duty, and desire to obey him; but the third, a reckless, domineering fellow, seizes the helm, lets the sail fill, and attempts to run by, mean-time declaring at the top of his voice that the cutter has no business to stop his progress. The others dare not resist him and cannot persuade him. Now, then, what position will they take as to the right of the revenue-officer to fire? Ten to one they will join their comrade whom they lately opposed; they will cry out, that the pursuer was wrong in ordering them to stop, and ought not to punish them for disobedience; in short, they will be converted by the instinct of self-preservation into advocates of the right of peaceable secession. I understand, indeed I know, that there are a few opponents of disunion remaining in South Carolina; but, although they are wealthy people and of good position, it is pretty certain that they have not an atom of political influence.

eemed so when I was there in January, 1861, and yet it did not seem so when I was there in 1855 and ’56. At that time you could find men in Charleston who held that the right of secession was but the right of revolution, of rebellion,—well enough, if successful, but inductive to hanging, if unfortunate. Now those same men nearly all argue for the right of peaceable secession, declaring that the State has a right to go out at will, and that the Federal Government has no right to coerce or punish it. These turncoats are the sympathetic, who are carried away by a rush of popular enthusiasm, and the fearful or peaceable, who dread or dislike violence. Let us see how a timid Unionist can be converted into an advocate of the right of secession. Let us suppose a boat with three men on board, which is hailed by a revenue-cutter, with a threat of firing, if she does not come to. Two of these men believe that the revenue-officer is performing a legal duty, and desire to obey him; but the third, a reckless, domineering fellow, seizes the helm, lets the sail fill, and attempts to run by, mean-time declaring at the top of his voice that the cutter has no business to stop his progress. The others dare not resist him and cannot persuade him. Now, then, what position will they take as to the right of the revenue-officer to fire? Ten to one they will join their comrade whom they lately opposed; they will cry out, that the pursuer was wrong in ordering them to stop, and ought not to punish them for disobedience; in short, they will be converted by the instinct of self-preservation into advocates of the right of peaceable secession. I understand, indeed I know, that there are a few opponents of disunion remaining in South Carolina; but, although they are wealthy people and of good position, it is pretty certain that they have not an atom of political influence.

Secession peaceable! It is what is most particularly desired at Charleston, and, I believe, throughout the Cotton States. Certainly, when I was there, the war-party, the party of the “Mercury,” was not in the ascendant, unless in the sense of having been “hoist with its own petard” when it cried out for immediate hostilities. Not only Governor Pickens and his Council, but nearly all the influential citizens, were opposed to bloodshed. They demanded independence and Fort Sumter, but desired and hoped to get both by argument. They believed, or tried to believe, that at last the Administration would hearken to reason and grant to South Carolina what it seemed to them could not be denied her with justice. The battle-cry of the “Mercury,” urging precipitation even at the expense of defeat, for the sake of uniting the South, was listened to without enthusiasm, except by the young and thoughtless.

“We shall never attack Fort Sumter,” said one gentleman. “Don’t you see why? I have a son in the trenches, my next neighbor has one, everybody in the city has one. Well, we shan’t let our boys fight; we can’t bear to lose them. We don’t want to risk our handsome, genteel, educated young fellows against a gang of Irishmen, Germans, British deserters, and New York roughs, not worth killing, and yet instructed to kill to the best advantage. We can’t endure it, and we shan’t do it.”

This repugnance to stake the lives of South Carolina patricians against the lives of low-born mercenaries was a feeling that I frequently heard expressed. It was betting guineas against pennies, and on a limited stock of guineas.

Other men, anti-secessionists even, assured me that war was inevitable, that Fort Sumter would be attacked, that the volunteers were panting for the strife, that Governor Pickens was excessively unpopular because of his peaceful inclinations, and that he would soon be forced to give the signal for battle. Once or twice I was seriously invited to stay a few days longer, in order to witness the struggle and victory of South Carolina. However, it was clear that the enthusiasm and confidence of the people were no longer what they had been. Several dull and costly weeks had passed since the passage of the secession ordinance. Stump-speeches, torchlight-processions, fireworks, and other jubilations, were among bygone things. The flags were falling to pieces, and the palmettos withering, unnoticed except by strangers. Men had begun to realize that a hurrah is not sufficient to carry out a great revolution successfully; that the work which they had undertaken was weightier, and the reward of it more distant, if not more doubtful, than they had supposed. The political prophets had been forced, like the Millerites, to ask an extension for their predictions. The anticipated fleet of cotton-freighters had not arrived from Europe, and the expected twelve millions of foreign gold had not refilled the collapsed banks. The daily expenses were estimated at twenty thousand dollars; the treasury was in rapid progress of depletion; and as yet no results. It is not wonderful, that, under these circumstances, the most enthusiastic secessionists were not gay, and that the general physiognomy of the city was sober, not to say troubled. It must not be understood, however, that there was any visible discontent or even discouragement. “We are suffering in our affairs,” said a business-man to me; “but you will hear no grumbling.” “We expect to be poor, very poor, for two or three years,” observed a lady; “but we are willing to bear it, for the sake of the noble and prosperous end.” “Our people do not want concessions, and will never be tempted back into the Union,” was the voice of every private person, as well as of the Legislature. “I hope the Republicans will offer no compromise,” remarked one excellent person who has not favored the revolution. “They would be sure to see it rejected: that would humiliate them and anger them; then there would be more danger of war.”

Hatred of Buchanan, mingled with contempt for him, I found almost universal. If any Northerner should ever get into trouble in South Carolina because of his supposed abolition tendencies, I advise him to bestow a liberal cursing on our Old Public Functionary, assuring him that he will thereby not only escape tar and feathers, but acquire popularity. The Carolinians called the then President double-faced and treacherous, hardly allowing him the poor credit of being a well-intentioned imbecile. Why should they not consider him false? Up to the garrisoning of Fort Sumter he favored the project of secession full as decidedly as he afterwards crossed it. Did he think that he was laying a train to blow the Republicans off their platform, and leave off his labor in a fright, when he found that the powder-bags to be exploded had been placed under the foundations of the Union? The man who could explain Mr. Buchanan would have a better title than Daniel Webster to be called The Great Expounder.

During the ten days of my sojourn, Charleston was full of surprising reports and painful expectations. If a door slammed, we stopped talking, and looked at each other; and if the sound was repeated, we went to the window and listened for Fort Sumter. Every strange noise was metamorphosed by the watchful ear into the roar of cannon or the rush of soldiery. Women trembled at the salutes which were fired in honor of the secession of other States, fearing lest the struggle had commenced and the dearly-loved son or brother in volunteer uniform was already under the storm of the columbiads. One day, a reinforcement was coming to Anderson, and the troops must attack him before it arrived; the next day, Florida had assaulted Fort Pickens, and South Carolina was bound to dash her bare bosom against Fort Sumter. The batteries were strong enough to make a breach; and then again, the best authorities had declared them not strong enough. A columbiad throwing a ball of one hundred and twenty pounds, sufficient to crack the strongest embrasures, was on its way from some unknown region. An Armstrong gun capable of carrying ten miles had arrived or was about to arrive. No one inquired whether Governor Pickens had suspended the law of gravitation in South Carolina, in view of the fact that ordinarily an Armstrong gun will not carry five miles,—nor whether, in such case, the guns of Fort Sumter might not also be expected to double their range. Major Anderson was a Southerner, who would surrender rather than shed the blood of fellow-Southerners. Major Anderson was an army-officer, incapable by his professional education of comprehending State rights, angry because he had been charged with cowardice in withdrawing from Fort Moultrie, and resolved to defend himself to the death.

In the meantime, the city papers were strangely deficient in local news concerning the revolution,—possibly from a fear of giving valuable military information to the enemy at Washington. Uselessly did I study them for particulars concerning the condition of the batteries, and the number of guns and troops,— finding little in them but mention of parades, soldierly festivities, offers of service by enthusiastic citizen’s, and other like small business. I thought of visiting the islands, but heard that strangers were closely watched there, and that a permit from authority to enter the forts was difficult to obtain. Fortune, or rather, misfortune, favored me in this matter.