Crawfordville [Ga.], Aug. 25th, 1860.

Dear Smith, I have been absent two weeks—went over to Sparta where I could be more completely retired and at rest—got back health—found your letter of the 18th inst., etc. I have promised to make a speech next week in Augusta. This was in response to a call from some 130 or 40 persons of that place. It was very much against my will to do it, but the call was of such a character I could not refuse. I suppose I shall have to permit the use of my name as an elector. This is a great embarrassment to me. I was almost offended at those who put it forward. I had expressly forbidden it. They ought not to have done it. But now the question for me is whether I shall sacrifice my individual feelings or permit myself to be the cause of injury to principles which lie so near my heart. Were I to decline, the reasons would never go with the act. I therefore [think it] better to suffer individually than for the public to suffer through me. This is the light in which I view it. I cannot write my letter immediately. Our court sit[s] here next week. I must attend to its business. That being on my mind I am not in condition to write on public affairs. Douglas is gaining rapidly in Georgia. The idea that Breckinridge must carry the State by 40,000 majority is all gammon in my judgment. He will however carry the State I think—if not by the popular vote at least before the Legislature. But if he carries the popular vote it will not be by a large majority unless I am greatly mistaken, and if he loses the popularity in the State, and Ky., Tenn., and Va., with N. C. and Mo. vote for Bell, I think there will be a chance for his losing the vote of the Legislature. That body will in that event be much more impressible than at present. How it will turn out however I can not now venture any satisfactory opinion. Public sentiment in the State is now in a tumult.

The caldron is just beginning to boil. It will get worse daily. Fermentation sometimes seems much higher than is expected when it first set in. Contrary to my expectations and what I knew at the time to be his feelings when I wrote you last, my brother Linton has taken the stump. He is to speak tonight in Augusta. He had no idea of this two weeks ago—none in the world—but his feelings have become very warmly enlisted in the national cause. Men who a few weeks ago cared or thought but little of the questions crowding themselves upon public attention are now like him beginning to realize the dangers ahead. To what extent this reaction, if it may be so termed, will go I cannot say. As for myself I look to the future with but little hope. The great evil of the day is the want of that high tone of political integrity and loyalty to principle which constitute the basis and lie [at] the foundation of all republican or representative government. These are virtues without which our Govnt. cannot stand. I doubt if there is enough pure disinterested patriotism in the land to save it. The signs now point to a speedy national rupture; and the same causes that will bring about that result will inevitably lead very soon to general anarchy. When a people lose or fall from a high tone of political morality they like individual men who have lost character and principles, become ready for anything. The right and the truth of any matter is not what they desire or look for but everything that will provide indulgence to their base propensities. This has been the history of the world and mankind everywhere. We are no better by nature than other people—no better than were the Greeks, the Romans or the French. The only difference thus far between us and the last named nation has been that our public men have been more thoroughly schooled in sound principles of political morality. In our worst crises of corruption there has been a predominance of public virtue and loyalty to the country in the national councils. This I fear is not the case now. Who in the Senate or House of Representatives would risk his reelection upon the advocacy of what his convictions assured him was right in itself, if he apprehended even that his seat should be hazarded thereby ? This is our trouble South as well as North. But I must close this homily. Continue to let me know the varying prospect as new features present themselves in the canvass in the different sections and states. These are always better and sooner perceived and understood at the centre than in the more distant parts. Send me the vol. of the Cyclopoedia when the one you mention is ready for delivery.

From Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1911.

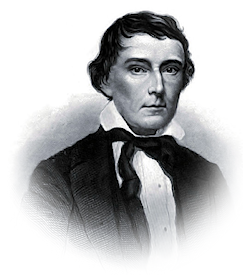

Alexander Hamilton Stephens was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. After serving in both houses of the Georgia General Assembly, he won election to Congress, taking his seat in 1843. After the Civil War, he returned to Congress in 1873, serving to 1882 when he was elected as the 50th Governor of Georgia, serving there from late 1882 until his death in 1883.

J. Henley Smith was a Georgia journalist.