Crawfordville [Ga.], July 2d, 1860.

Dear Smith, Your letter was received two days ago and I delayed answering it until I should get the paper containing the communication referred to in it. This came to hand last night. I read it with interest and was highly pleased with the general tone and style. You present the strong points of the case. In some minor matters you were not quite so effective as you might have been. These I intended to call your attention especially to, but some person took the paper away last night (there were several at the house) and I have not got it to refer to. But one I recollect very distinctly and will name. After stating Mr. Douglas’s position very clearly in which he puts slave property in the territories upon the same footing as all other property, etc., you go on to say, “and yet because the party South disagreed with him upon one vital point they warred against him.” I have not got your words but the idea. Now you should not have styled this a vital point. It should have been immaterial, for it is an immaterial and not a vital point of difference—and if it were a vital, as his opponents allege it to be, would it not

justify their opposition? Can vital points ever be waived? Your whole letter shows that it is not a vital point; and if you had used the word immaterial instead of vital in this connection it would have added great force to your general argument. There were two or three other matters I intended to call your attention to. These related to your historical narrative, but I have forgotten them. But I assure you this letter and your previous one on the whole present Douglas’s claims in a stronger light than I have seen them presented in any Southern paper. I have not seen a speech or an article by a Southern man that has been of real benefit to him except yours not one that met the issue on the right points. No man ever had more cause to exclaim save me from my friends than Douglas has, particularly from his friends at the South. I was surprised at their course at Baltimore. What could they mean by pushing his nomination in the face and teeth of the secession of Tenn., Ky., and Va., to say nothing of the other states, I cannot understand. I may be mistaken. I have heard no explanation of it. I do not know what they rely upon or what their calculations are. I have no lights except what I get from general views and my knowledge of the workings of causes to their effects. But from these lights it does seem to me that this course was neither wise nor patriotic. Madness and folly must have ruled the hour. They put up their man to be beaten. I do sincerely trust it may be otherwise, but I do not see any probable chance for him. Had he been nominated over the votes of the Tenn., Ky., and Va., delegations—had he got two thirds according to the usages which may be regarded as the constitution of the National Democratic organization, had those states adhered to the nomination, then my opinion is that he would have carried them with Ala., La., and Mo., and with enough Northern votes to secure his election. But with the break of the great border States, who that has got sense enough to get out of a shower of rain does not know that even though a ticket may be run for him in those states, yet that it is impossible for him to carry them or either of them? And who does not know that when it is apparent that he will lose the entire south, thousands of men at the North, some for spite and some to get on the winning side, will quit his standard then, and thus leave him perhaps without the vote of a single state? As for his carrying Ala., under existing circumstances, I have no idea. And why the delegation of that State and La. should have persisted in having him nominated with all these considerations before them, I cannot imagine. I can attribute it to nothing short of dementation. I may be mistaken. I hope I am. I would say nor do nothing to weaken their efforts; but as a quiet observer feeling however a deep interest in the general result upon the welfare of the country, I give you freely my candid impressions and convictions at this present writing. I repeat, I maintain these opinions upon general principles only. I have heard no explanations and have no communication with the outside world except through the medium of the public press. I am pained and grieved at the folly which thus demanded the sacrifice of such a noble and gallant spirit as I believe Douglas to be. I can see but one possible good that his nomination may effect, and that is he may get enough electoral votes at the North to defeat Lincoln in the colleges and thus throw [it] in the House where he may be the stepping stone for his party rival (Breckinridge) to rise into office. His back and shoulders may enable his rival to elevate himself to place and honor and in this way attain the object of his ambition, and in this way the country may possibly be benefitted in the ultimate defeat of Lincoln. But what honor this will be to Douglas his friends must determine. They certainly have much less regard for that than I have. If such a position had been necessary for anyone to occupy I would have assigned it to some other one, someone who while rendering public service would have gained instead of losing reputation. I would not have called upon Douglas to do it. Indeed I think it was very unwise to put him or anybody in nomination without the 2/3 vote. It will be regarded as a violation of the constitution of the party and would of itself be sufficient to justify any man who felt disposed from any cause to consider himself as absolved from all obligation to conform to party action. The whole affair therefore I regard exceedingly unfortunate. I see nothing but disaster attending it. I assure you the wish is far from being the father to the thought in this case. I give but the honest convictions that are forced upon my mind, and shall be rejoiced if when the smoke of the battle field clears away I shall see a more encouraging prospect. I take no Northern paper and do not know how the public sentiment there is running. But I do know that the doctrine of non-intervention was never popular there. It was an up hill business to support and sustain it. It broke down the Democratic party. Those who sustained themselves on it did it only in the defensive. It contained no element that addressed itself to the heart of the people. It had no rallying heart for the masses. No converts would ever be made by appealing in its behalf. It was always a question simply of how many would be lost by its advocacy. I have seen nothing to cause me to believe that any change has taken place in the great popular sentiment on this subject in that section. Hence I do not see where Douglas is to gain. The administration will throw all its power against him. This is his only hope for gains in the North. But the old feeling of hate on the part of the Democrats who quit the party on account of this doctrine will seize the opportunity of pouring out all the vials of their wrath against him when they see a prospect of his humiliation. Had the party not split, had he been run at the South with a reasonable show of success there, he would have made great gains from the conservative Union-loving portion of the people North. But there is now nothing to rally that portion unless they see prospects of electing him solely by Northern votes. This I do not think within the range of possibility. What then is to be the result? God only knows. I can say no more. This letter is strictly and exclusively for yourself. I am still confined to the house; do not go out and have no idea that I shall be able to do anything but rest during the heat of summer. I hope I shall not have to take my bed. If I can keep up I shall be content. I wish if you see anything of interest in any Northern paper, the Times, the Herald, or Tribune, or any other, you would buy a copy of the number and send to me. Keep an account and I will pay the amounts. I take none of these papers but would like to see anything of interest in them. What did you mean by referring to certain dispatches in some of the Northern papers about me during the Baltimore Convention in one of your letters to the Confederacy? I did not understand your allusion and do not now. Write often.

From Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1911.

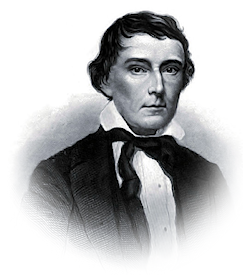

Alexander Hamilton Stephens was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. After serving in both houses of the Georgia General Assembly, he won election to Congress, taking his seat in 1843. After the Civil War, he returned to Congress in 1873, serving to 1882 when he was elected as the 50th Governor of Georgia, serving there from late 1882 until his death in 1883.

J. Henley Smith was a Georgia journalist.