Crawfordville, [Ga.], Sept. 16th, 1860.

Dear Smith, This is Sunday as you see from the date. Yesterday I wrote you a long letter. Last night I got the third and last slip from the Constitution in review of my Augusta speech. I notice nothing in any of these pieces that I feel any desire to answer or to have answered. The last piece is very disingenuous in one particular—that is in its attempt to make me inconsistent with myself on the matter of abstract principles. But this is quite apparent to all who are familiar with the facts. In my speech of July 1859 on the importance of maintaining abstract principles at any cost and hazard I spoke definitely and particularly of those abstract principles effecting any essential interest, right or honor; and in the speech of 1st Sept. 1860 I stated distinctly that the principle of allowing the territorial legislatures to settle the question of slavery did not involve any essential right, our present security, future safety, or honor. So the effort to show off my inconsistency was a vain and futile one. Indeed in that speech of July 1859 I stated that it was useless to war against those who refused to give us congressional protection in the Territories—that there was nothing practical or essential to our rights, interest or honor in it. I have not the speech before me, but I know this was the substance of it; and I doubt not the reviewer knew it too very well. But let it all pass—as I said yesterday the right and the truth is not what these secessionists and revolutionists are after. Their object is to hide the truth. Personal spite is their aim, and not the public good. They rely upon misleading the people hj appeals to their passions and prejudices. This is the policy of all bad men bent upon mischief. Their game is that of the demagogue always a low, mean and base one. The people by nature are prone to error. Their inclinations in politicks are that way as in morals they are to sin. To do right, to counteract these inclinations in the one sphere or the other, requires an effort. The high mission of a patriot and a statesman is by appeals to truth and virtue to raise the good sense of the masses above their natural propensities, to get them to do right against their natural inclinations. Herein lies the difference between a demagogue and a statesman. It was this high and ennobling quality that caused Webster to tell the men of Boston that they must “conquer their prejudices “, as the same great quality caused Aristides on one occasion to say “O Athenians, what Themistocles proposes is greatly to your interest, but it is unjust” Our demagogues look to nothing but success and rely upon nothing but the weakness of human nature in yielding to their selfish propensities. Such practices have always been the forerunners of the overthrow of all republics. Free institutions, representative government, can be maintained only by the intelligence and virtue of the people. These are the sustaining fountains of patriotism, and when these fountains fail or become polluted patriotism ceases, love of country sours into a rabid passion of undefined rage and hate without aim or object, driving the unfortunate subjects to the wildest and most reckless ends. Such has been the history of all popular governments. The first fatal step has been that of those who, entitled to their confidence, misled the masses instead of keeping them ton the right, even against their seeming interests and their strong natural erroneous inclinations and propensities. This in all times past has most generally as is the case in our country now, originated in the selfishness and ambition, in the personal likes, dislikes and hates, in the rivalships of public aspirants. For it is a sad and melancholy truth, such is the frailty and weakness of human nature, that even the best of patriots generally hate their enemies or rivals more than they love their Country. From this weakness or imperfection of man’s constitution come most of the evils and troubles which disturb the peace, unsettle the foundations and destroy the prosperity and happiness of the wisest and best constituted human societies and governments. These are the evils and troubles that now beset and threaten this fair and happy land, this land of hope and promise to the world. There is a war among the leaders and aspirants for public favour and public trust. It is not a contest for the wisest, safest and soundest policy looking to the security of the rights, interest, welfare and prosperity of all parts and sections of the country. So far from it, it is a contest based upon disloyalty to principle, upon abandonment of principle, and waged with an audacious effort to make the public believe a lie, that there is no abandonment of principle but that the object is to subserve their interests.

This is the state of things here at this time. Its parallel or prototype is to be found in all incipient revolutions. I can look upon it in no other light; and as like produces like in the moral and political as well as the physical world, I look to the same almost inevitable result. The contemplation is a sad one. It presents but little ground of hope. Had revolution been forced upon us as it was upon the colonies by a violation of principle, by the assertion of unjust power incompatible with our security and safety, my hopes and views of the future would be altogether different from what they are. Men who set out in a revolution by an abandonment of the principles and professions of their lives offer no guaranty to me that they will conduct it to any good result. Their conduct shows that other objects than the public welfare are at the bottom of their movement. These objects are personal, and all things in the end as in the beginning will be made to tend to these same purposes, which purposes are utterly inconsistent with any well-grounded hope for good government. The future to me therefore is gloomy enough! Whether there is virtue and patriotism sufficient in the country to realize its situation and arrest the evil tendency before it is too late I do not know. I cannot answer that question satisfactorily to myself. But perhaps I have tired you with this long Jeremiad, as you may consider it, and therefore I will say no more. Why do you not continue to send me the New York papers? I have got none lately. Have they ceased to be interesting? Have they become as dark and as incapable of throwing light upon the future as my own incoherent speculations? I feel anxious to know how the fusion movements succeeded in N. Y. and Pa. In them lay my only hope for the defeat of Lincoln. I have seen nothing about that matter in Pa. In New York I saw that the Americans and National Democrats had united and that it was expected that the Secession Democrats would also join in the union. But whether they have or not I have not seen. And I am intensely ignorant or uninformed as to how matters stand in Pa. Write to me to Kingston on these points and send your newspapers to that place. I am feeling better today in health than I have felt for several weeks. The weather is still pleasantly cool.

From Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1911.

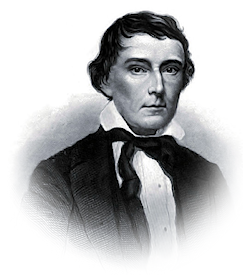

Alexander Hamilton Stephens was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. After serving in both houses of the Georgia General Assembly, he won election to Congress, taking his seat in 1843. After the Civil War, he returned to Congress in 1873, serving to 1882 when he was elected as the 50th Governor of Georgia, serving there from late 1882 until his death in 1883.

J. Henley Smith was a Georgia journalist.