Crawfordville [Ga.], Sept. 15th, 1860.

Dear Smith, The second slip from the Constitution was received last night. I still see in this review not one thing that I desire to answer or see answered. As to the remarks and comments of the writer on my candour, etc., of course that is a matter beyond the reach of proof or disproof. Those who know me must judge of it for themselves and those who do not would be influenced very little by any discussion upon the subject. The truth is I have almost despaired of the Republic. Sometimes I take or catch the glimpse of a faint hope, and then the stunning truth seems to flash me full in the face that we are rushing rapidly to the brink of destruction! The times are all sadly out of joint. Men have no regard for past principles or professions. Consistency is wholly disregarded. Passion and prejudice rule the hour; reason has lost its sway. The truth and the right are not sought after. Public virtue is no longer held in its proper estimation, and all our discussions remind me more of the wranglings of the Jacobins in France than anything else. I mean the discussions on the stump and in the newspapers. Perhaps I should not say all. Mr. Douglas’s speeches are an exception. In all of them that I have seen he holds a high and statesmanlike position and in them breathes a lofty, national and patriotic tone. But I see no response to this tone either North or South. Most of the Douglas papers and speakers with us seem to me not to rise to the real gravity and dignity of the questions before the country. I do not believe they realize the magnitude of the issues involved. Douglas’s speech at Baltimore I think is decidedly the best he has made. Had the whole South planted themselves upon the doctrines and principles of that speech as they ought, all would have been well with us. But they will not, and as I look out upon the country and contemplate the probable future I feel as Jesus did when he came near the city of Jerusalem and wept over it, “saying if thou hadst known even thou at least in this thy day the things that belong unto thy peace, but now they are hid from thine eyes!” Such are my feelings. I may be in error, and those who are driving events as they go may come out right at last. If they do no one will be more rejoiced than I; but I can see no probability of such a fortunate result. To me at present all is gloom and darkness. I have seen partial returns from the election in Maine. This I fear is but a sample of the public sentiment at the North generally. With a divided Democracy what better could have been expected? This is but the realization of my first conviction when the rupture was consummated at Baltimore. What will now come of the attempts of fusion in N. Y. and Pa.? There lie our only hopes for the defeat of Lincoln. Will these attempts succeed, or will not the prevailing sentiment of the North, encouraged by our divisions sweep everything before it? This I now seriously fear. And if so what then? Yes, as I said in Augusta, what then? The question oppresses me. I feel well assured that the bare election of any man under the constitution is not sufficient cause for the withdrawal of any State. But are there not several States that will do it? And if the attempt even is made, who can tell the ultimate consequences? Oh my country, what is to become of it?

I am as you see still at home. I have improved a good deal in strength within the last week since the cool weather set in, but am yet unable to undertake any physical exertion. I have given up all idea of taking any active part in the present canvass. I see no good that anything I can say will accomplish, even if I had the strength to say anything, without serious injury to myself. I may be too desponding, but I really look upon all as lost, not only the party and its principles, but the country. These sentiments you may keep to yourself, for I do not wish my depression of spirits to affect in the least those who are more sanguine. Let those who have hopes remit no effort to attain their object. Write to me forthwith to Kingston what you think from a survey of the whole field. I shall go to the upcountry next week and remain there the week after. At Kingston I can get your letter.

From Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1911.

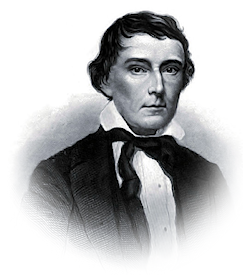

Alexander Hamilton Stephens was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. After serving in both houses of the Georgia General Assembly, he won election to Congress, taking his seat in 1843. After the Civil War, he returned to Congress in 1873, serving to 1882 when he was elected as the 50th Governor of Georgia, serving there from late 1882 until his death in 1883.

J. Henley Smith was a Georgia journalist.