Crawfordville [Ga.], Sept. 12th, 1860.

Dear Smith, Your letter of the 8th inst. enclosing editorial of the Constitution was received last night. I wrote to you a few days ago. In that letter I believe I told you I expected this week to go to the mountain country with a view of recruiting strength, health, etc. But I am still here as you perceive. A very sudden change of temperature caused me to postpone my travel. It is now very cool here. In the up-country I suppose it is quite uncomfortable in the mornings and evenings for an invalid, without fire. Such weather is unsuitable for me to be away from home in. But enough of this. I only meant to let you know why I am still at home. As to the article in the Constitution, I do not think it requires any answer or reply—not even a notice, at least from me. The Va., Ky., Tenn., and N. C. and Ga. delegations bolted at Baltimore because the seceders from Ala. and La. were not permitted to take the seats that they had abandoned and because the convention assigned the seats to those delegates which the Democracy of Ala. and La. had sent up to fill the vacancies etc. according to the call of the convention. This is the whole of it. These very states of Va., Tenn., Ky., etc., had asked the Democracy of the states whose delegates had seceded at Charleston to send up other delegates to fill their places. This they did and then instead of standing by those who had been sent at their call they turned and joined the seceders themselves. The pretence was that the seceders were the true representatives of the Democracy of their states—and that too after they had joined another organization, adopted another name and [had] even [been] commissioned to another convention to be held at another place, etc. My judgment was and is that the seceders had unpartyed themselves and should not have been admitted from any state whether there was a representation of the National Democracy from it or not. But when all the States seceded who chose to do so, from whatever cause, there was a quorum of the convention left—and Douglas got a two-thirds vote of that quorum and is the regular nominated candidate of the party. That is my point, and there is no getting round it or under it or over it. Men may bolt when they please, but they cannot escape the proper characterization of their deed. My opinion is that the whole rupture at Charleston and Baltimore is chargeable entirely upon the Southern bolters. They ran not from a platform but from a man. The platform was a pretext. The whole rupture originated in personal ambition, spite and hate. This is my deliberate opinion. I cannot however say more. I have not yet seen Mr. Breckinridge’s Lexington speech—am anxious to see it—am anxious also to hear from the Maine election. Not a word yet have we heard from that. I am apprehensive that the Republicans have increased their majority. In this State the tendencies are favourable to Douglas—becoming more so daily. If there was any prospect of his election a perfect enthusiasm could be got up for him—much more than for any other candidate. But his chances seem to be [a] hopeless battle before the people and in the House, and hence the indifference of thousands who would otherwise be active, warm and zealous in his cause. It is now thought here that Lincoln will be defeated, that the election will go into the House and if Douglas, Lincoln and Bell should be the three returned to the House may be Douglas might be chosen. But we shall see what we shall see. My greatest desire is to defeat Lincoln and thus prevent the evils that such an event might precipitate upon us.

From Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1911.

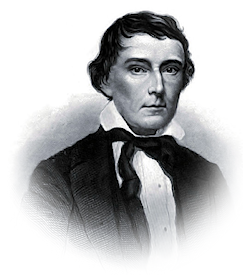

Alexander Hamilton Stephens was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. After serving in both houses of the Georgia General Assembly, he won election to Congress, taking his seat in 1843. After the Civil War, he returned to Congress in 1873, serving to 1882 when he was elected as the 50th Governor of Georgia, serving there from late 1882 until his death in 1883.

J. Henley Smith was a Georgia journalist.