From the diary of Osborn H. Oldroyd

MAY 12TH–Roused up early and before daylight marched, the 20th in the lead. Now we have the honored position, and will probably get the first taste of battle. At nine o’clock slight skirmishing began in front, and at eleven we filed into a field on the right of the road, where another regiment joined us on our right, with two other regiments on the left of the road and a battery in the road itself. In this position our line marched down through open fields until we reached the fence, which we scaled and stacked arms in the edge of a piece of timber. No sooner had we done this than the boys fell to amusing themselves in various ways, taking little heed of the danger about to be entered. A group here and there were employed in “euchre,” for cards seem always handy enough where soldiers are. Another little squad was discussing the scenes of the morning. One soldier picked up several canteens, saying he would go ahead and see if he could fill them. Soon after he disappeared, he returned with a quicker pace and with but one canteen full, saying, when asked why he came back so quick–”while I was filling the canteen I heard a noise, and looking up discovered several Johnnies behind trees, getting ready to shoot, and I concluded I would retire at once and report.” Meanwhile my bedfellow had taken from his pocket a small mirror and was combing his hair and moustache. Said some one to him. “Cal., you needn’t fix up so nice to go into battle, for the rebs won’t think any better of you for it.”

DeGolier’s Battery going into action at the Battle of Raymond.

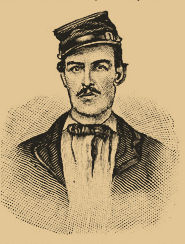

Just here the firing began in our front, and we got orders : “Attention ! Fall in–take arms–forward–double-quick, march!” And we moved quite lively, as the rebel bullets did likewise. We had advanced but a short distance–probably a hundred yards–when we came to a creek, the bank of which was high, but down we slid, and wading through the water, which was up to our knees, dropped upon the opposite side and began firing at will. We did not have to be told to shoot, for the enemy were but a hundred yards in front of us, and it seemed to be in the minds of both officers and men that this was the very spot in which to settle the question of our right of way. They fought desperately, and no doubt they fully expected to whip us early in the fight, before we could get reinforcements. There was no bank in front to protect my company, and the space between us and the foe was open and perfectly level. Every man of us knew it would be sure death to all to retreat, for we had behind us a bank seven feet high, made slippery by the wading and climbing back of the wounded, and where the foe could be at our heels in a moment. However, we had no idea of retreating, had the ground been twice as inviting; but taking in the situation only strung us up to higher determination. The regiment to the right of us was giving way, but just as the line was wavering and about to be hopelessly broken, Logan dashed up, and with the shriek of an eagle turned them back to their places, which they regained and held. Had it not been for Logan’s timely intervention, who was continually riding up and down the line, firing the men with his own enthusiasm, our line would undoubtedly have been broken at some point. For two hours the contest raged furiously, but as man after man dropped dead or wounded, the rest were inspired the more firmly to hold fast their places and avenge the fallen. The creek was running red with precious blood spilt for our country. My bunkmate[1] and I were kneeling side by side when a ball crashed through his brain, and he fell over with a mortal wound. With the assistance of two others I picked him up, carried him over the bank in our rear, and laid behind a tree, removing from his pocket, watch and trinkets, and the same little mirror that had helped him make his last toilet but a little while before. We then went back to our company after an absence of but a few minutes. Shot and shell from the enemy came over thicker and faster, while the trees rained bunches of twigs around us.

One by one the boys were dropping out of my company. The second lieutenant in command was wounded; the orderly sergeant dropped dead, and I find myself (fifth sergeant) in command of the handful remaining. In front of us was a reb in a red shirt, when one of our boys, raising his gun, remarked, “see me bring that red shirt down,” while another cried out, “hold on, that is my man.” Both fired, and the red shirt fell–it may be riddled by more than those two shots. A red shirt is, of course, rather too conspicuous on a battle field. Into another part of the line the enemy charged, fighting hand to hand, being too close to fire, and using the butts of their guns. But they were all forced to give way at last, and we followed them up for a short distance, when we were passed by our own reinforcements coming up just as we had whipped the enemy. I took the roll-book from the pocket of our dead sergeant, and found that while we had gone in with thirty-two men, we came out with but sixteen–one-half of the brave little band, but a few hours before so full of hope and patriotism, either killed or wounded. Nearly all the survivors could show bullet marks in clothing or flesh, but no man left the field on account of wounds. When I told Colonel Force of our loss, I saw tears course down his cheeks, and so intent were his thoughts upon his fallen men that he failed to note the bursting of a shell above him, scattering the powder over his person, as he sat at the foot of a tree.

Hand-to-hand conflict.

Although our ranks have been so thinned by to-day’s battle our will is stronger than ever to march and fight on, and avenge the death of those we must leave behind. I am very sad on account of the loss of so many of my comrades, especially the one who bunked with me, and who had been to me like a brother, even sharing my load when it grew burdensome. He has fallen; may he sleep quietly under the shadows of those old oaks which looked down upon the struggle of to-day.

We moved up to the town of Raymond and there camped. I suppose this will be named the battle of Raymond. The citizens had prepared a good dinner for the rebels on their return from victory, but as they actually returned from defeat they were in too much of a hurry to enjoy it. It is amusing now to hear the boys relating their experiences going into battle. All agree that to be under fire without the privilege of returning it is uncomfortable–a feeling which soon wears off when their own firing begins. I suppose the sensations of our boys are as varied as their individualities. No matter how brave a man may be, when he first faces the muskets and cannon of an enemy he is seized with a certain degree of fear, and to some it becomes an occasion of an involuntary but very sober review of their past lives. There is now little time for meditation; scenes change rapidly; he quickly resolves to do better if spared, but when afterward marching from a victorious field such good resolutions are easily forgotten. I confess, with humble pleasure, that I have never neglected to ask God’s protection when going into a fight, nor thanking him for the privilege of coming out again alive. The only thought that troubles me is that of falling into an unknown grave.

The battle to-day opened very suddenly, and when DeGolier’s battery began to thunder, while the infantry fire was like the pattering of a shower, some cooks, happening to be surprised near the front, broke for the rear carrying their utensils. One of them with a kettle in his hand, rushing at the top of his speed, met General Logan, who halted him, asking where be was going, when the cook piteously cried, “Oh General, I’ve got no gun, and such a snapping and cracking as there s up yonder I never heard before.” The General let him pass to the rear.

Thomas Runyan [2], of Company A, was wounded by a musket ball which entered the right eye, and passing behind the left forced it out upon his cheek. As the regiment passed, I saw him lying by the side of the road, tearing the ground in his death struggle.

[1]

John Calvin Waddell, Corporal Co. E, 20th Ohio, killed May 12 1863.

[2] When the regiment was being mustered out in July, 1865, Thomas Runyan. who had been left for dead, visited the regiment. He said he came “to see the boys.” He was, of course, totally blind.